Baby, Baby

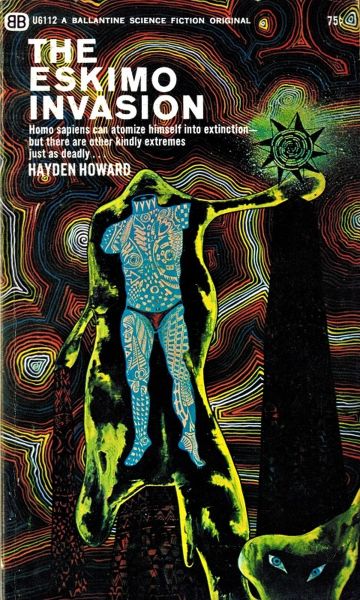

The Eskimo Invasion

By Hayden Howard

20 Aug, 2024

Hayden Howard’s 1967 The Eskimo Invasion is a fix-up of several satirical Population-Bomb science fiction stories.

The Eskimo Invasion isn’t so much an infamously bad science fiction work as it is an infamously obscure award-nominated science fiction work. Readers, fannish and professional, liked the series of short works enough to nominate the novelette The Eskimo Invasion for both the Hugo1 and the Nebula2. The fix-up was nominated for a Nebula2. However, the book went out of print almost immediately. The only time I’ve ever seen it discussed is in this Revisiting the Hugos thread. Therefore, stumbling across a reasonably priced MMPB, how could I not read it? How bad could it possibly be?

Former Director of Oriental Population Problems Research Dr. Joe West steals into Canada’s Eskimo Cultural Sanctuary.

Fearing the complete extinction of traditional native ways, Canada designed the Bootha Peninsula as the Eskimo Cultural Sanctuary. All post-contact technology was confiscated from the natives living in the region4. The borders were tightly controlled to prevent outsiders from interfering with the natural course of events. Policy precludes monitoring events in the Sanctuary, so nobody outside it is quite sure how the residents are faring. West plans to address that lack.

West finds a thriving population, one with a most curious age distribution. An astonishing fraction of the population are children. The reason for this is simple: the occupants of the Sanctuary are reproductively distinct from regular humans. Women need but a month for a full pregnancy. As West subsequently discovers, men are almost superfluous to the process, their services required but once to begin the cycles of pregnancy.

How this came to be is not clear. What is clear to West: first, that despite their apparent descent from local people, and despite their appearance, these people are a new species, the Esk. Second, unless something can be done to curtail their enthusiastic reproduction, the Sanctuary, Canada, and quite possibly the world face apocalypse. The Esk will swiftly outbreed any possible improvement in the food supply. Civilization will perish!

West returns to California, taking his Esk bride Marthalik with him. As Marthalik produces baby after baby, West ponders how best to manage the Esks’ reproduction for them. A sterilizing disease seems just the thing! After surreptitiously testing it on Marthalik (thus forever alienating her), West returns to the Sanctuary to unleash the sterilizing plague on the Esk.

Alas. There is a reason medical research involves test groups larger than one. Marthalik was unusually susceptible to West’s creation. The rest of the Esk are immune. This is not at all true for the unfortunate baseline human Eskimos living amongst the Esk. In short order, West finds himself on trial for attempted genocide.

West’s next bold venture is to find some way to escape from the comfortable Canadian prison in which he is immured for life. His gambit involves cryonics, as a result of which he sleeps away the next seventeen years.

Revived in 2010, he finds his nightmare scenario did not go far enough. West failed to foresee that economies dependent on endless growth would find the Esk quite useful. China in particular values its Esk population. Rather than preventing population doom, governments encourage it!

It’s up to West to save humanity! Or fail abjectly, which to be honest is more his speed.

~oOo~

It was probably never in the cards that someone who once ran Oriental Population Problems Research was going to react favorably to the Esk. Being extremely alarmed by other ethnicities’ birth rates was very fashionable in the 1960s5. West is an extreme case. The ease with which he decides Esk are not really human and that extreme measures are called for to manage them is not surprising.

As one might guess from the novel’s terminology, The Eskimo Invasion is filled with problematic elements. It’s something of a comprehensive tour of perspectives that no longer please us. That said, one cannot help but notice how often West’s predictions fall short and how often West’s bold efforts go horribly wrong. West may well be a confident, highly educated idiot.

The Eskimo Invasion is chonky for a mid-1960s SF novel. This is because it began as seven novelettes and novellas. Invasion meanders, also likely because it began as seven separate works, all of which could have benefited from streamlining. Howard has more than the Population Bomb on which to comment. There are academic fads to critique, the Military-Industrial Complex to poke fun at, prison reform to mock, paternalistic treatment of ethnic minorities to highlight, not to mention unfortunate portrayals of Chinese people to showcase. Invasion is in no hurry to reach its conclusion, although, thank merciful providence, eventually Invasion does end.

Although I didn’t enjoy the book all that much, and can’t recommend it, I will grant it has one unexpected virtue. There is a reason why the Esk appeared when they did and why they have the particular characteristics they do. It’s one that came as a complete surprise.

The Eskimo Invasion is out of print.

1: Losing to Jack Vance’s The Last Castle. The other finalists do not seem to have been ranked. They were Charles L. Harness’ An Ornament to His Profession, Robert M. Green, Jr.’s Apology to Inky, Gordon R. Dickson’s Call Him Lord, Roger Zelazny’s For a Breath I Tarry, Charles L. Harness’ The Alchemist, Howard’s The Eskimo Invasion, Thomas Burnett Swann’s The Manor of Roses, and Roger Zelazny’s This Moment of the Storm.

2: Losing to Gordon R. Dickson’s Call Him Lord, placing behind Charles L. Harness’ An Ornament to His Profession, and Robert M. Green, Jr.’s Apology to Inky, while coming in ahead of Roger Zelazny’s This Moment of the Storm.

3: Losing to Samuel R. Delany’s The Einstein Intersection, ranked behind Piers Anthony’s Chthon and Roger Zelazny’s Lord of Light, and ahead of Robert Silverberg’s Thorns.

4: Informed consent is not an issue with which anyone in power appears to concern themselves.

5: Worrying that Those People Over There are having too many babies is a running theme in human history.