Before Rissa and Bran

Zelde M’Tana

By F. M. Busby

12 Dec, 2015

0 comments

ISFDB lists 1980’s Zelde M’Tana as the third book in the Rissa Kerguelen series. Even though it was the last of the Kerguelen series to be published, it is not a sequel at all. It’s a prequel. Rissa doesn’t appear in this book; her man-candy Bran Tregare appears only towards the end. This novel focuses on the eponymous Zelde and her life before she crossed paths with Rissa.

When we first meet her, Zelde does not seem a likely candidate for star travel. She is one of North America’s Wild Children, with little memory of her long-lost parents or any other way of life; she’s only mostly sure that her name really is Zelde M’Tana. Zelde is snatched up by Rehabilitation, an agency with a do-good name and some do-bad methods and goals. After Zelde attacks a Rehab officer, she is scheduled for a lobotomy and life in the slave camps of Total Welfare.

Luckily for Zelde, there is such a thing as a kind-hearted Rehabilitation officer, who sees her as someone worth salvaging. Zelde is diverted to the UET (United Energy and Transport) starship Great Khan , the first step towards to what the official hopes will be a better life out in the stars. “Better” is a relative term: she is being exported as a sex slave, to a brothel on the distant mining colony Iron Hat.

But Great Khan will never reach Iron Hat.

UET is a grossly abusive employer (when it can be bothered to pay wages at all; as the absolute rulers of North America, they can sentence their subjects to slave labour). As one might expect, they mistreat their starship crews as well. Which is a mistake. The crews have the option to mutiny, steal a UET starship, and flee to one of the worlds beyond UET’s control. A faction within Great Khan ‘s crew has been planning a mutiny for some time. Long before the ship reaches Iron Hat, they make their move.

Is everything A‑OK for Zelde, liberated slave? Well, no. The mutineers soon split into quarrelling splinter groups; there is also a hidden, lurking cabal of UET loyalists. Parnell, who led the mutiny, finds his position threatened. The mutineers who dislike him extend their hatred to Zelde, now Parnell’s lover. Not only that, but the UET loyalists are plotting to seize the ship and kill the mutineers. And Zelde, of course.

Could it get worse? Yes. Great Khan ‘s drive is damaged. The only port in range with suitable facilities is Terranova.

And Terranova is very much a loyal UET world.

~oOo~

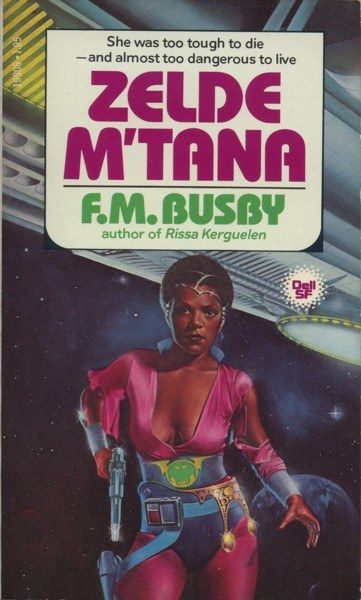

SF publishing (and publishing in general) has a long history of whitewashing protagonists; they may be POCs in the book, but they’re white in the cover art. Whatever else I may think of this cover

I can at least say that it’s not whitewashed. Nor is the cover of the later edition.

Zelde is bisexual, which the author clearly regarded as no big deal. And contrary to established tropes, Zelde’s female lovers are no more doomed than her male lovers. Unfortunately for everyone involved, they are not any less doomed. I suspect Zelde never had to buy Christmas gifts for the same lover or ex-lover twice. You would probably be safer volunteering for UXB duty than dating Zelde. This is in no way a reflection on Zelde’s character; it simply reflects the author’s determination to turn her life into a string of calamities.

I would be tempted to ascribe the tribes of wild kids who populate the beginning of the novel to the SFnal habit of extrapolating short-term crime rates (1960s and 1970s US) into the future; people really didn’t see the long term drop in crime rates coming1. But it’s just as likely that the Wild Children are just one of the many gifts UET gave North America: UET cops aren’t very diligent about rounding up the kids when they drag off the parents.

Starships in this setting seem very user-friendly2, something a bright kid off the streets can master in a few months. Given that UET’s idea of education is brutalizing kids into compliance, that’s probably a sensible design choice.

This novel is only about 316 pages. While it is highly episodic, it seems more focused than the Rissa Kerguelen omnibus. It also devotes many fewer words to telling us just how all-round wonderful the protagonist is. I would attribute this authorial restraint to the fact that this was Busby’s seventh novel. Practice helps.

As far as I can tell, Zelde M’Tana appeared in only a handful of printings and is now out of print. It should be available used

1: Some people believe that legalizing abortion (so that people weren’t having unwanted kids) and banning leaded gasoline and paint (so that the kids weren’t being brain-damaged by lead) may have been responsible for the drop in crime.

Some politicians (such as Stockwell “Doris” Day, of the late unlamented Conservative government of Canada) have had a hard time admitting that there was any drop in crime rates at all. Crime makes such a good boogeyman.

2: The fact that the ships are relativistic is also user friendly, because it means you can flee into a hopefully UET-less future if you take a long enough trip. That said, while the book acknowledges the fact of time dilation, such dilation does not play anywhere near as large a role in this book as it did in the Rissa books. Primarily because the Great Khan never visits any world twice within the timeline of this novel.