Below the Shadow of a Dream

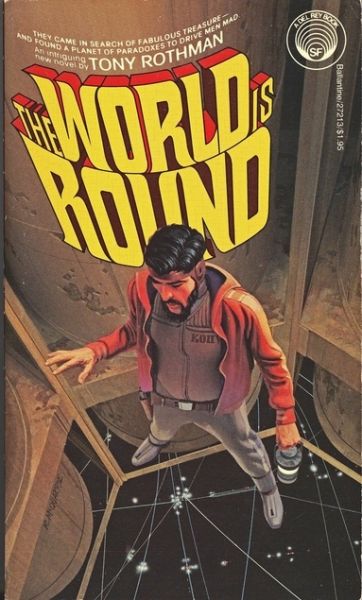

The World is Round

By Tony Rothman

28 Jun, 2020

Tony Rothman’s The World is Round was published in 1978.

Wealthy businessman Pike mounts an expedition to Barythron, a solar system just ten light-years from his home world, Two-Bit. Expedition crew: Pike, Hendig (who has visited Barythron and returned with tales of treasure), Valyavar, and Stringer.

Six years later (or ten, depending on your frame of reference), the starship Crimsonarrives at Barythron and the crew wakes from cold sleep to discover that Hendig’s tale is quite true. A planet fifty times the size of Two-Bit orbits the sun of Barythron. Now one might expect that such a large world would be a gas giant — but it isn’t. It appears to be quite solid, with habitable conditions on its surface. Not only that, it’s inhabited. A scientist would question this implausibility and advise extreme caution. But Pike finds scientists annoying and deliberately didn’t bring any.

The crew divides into two parties — Pike with Hendig, Stringer with Valyavar — and then heads to the surface. It does not take long for things to go very very wrong.

Stringer and Valyavar’s shuttle crashes on landing. They have been wrecked near the city of Ta-tjenen. When Stringer wakes, he is surrounded by strangers he assumes are hostile. He kills one of them before he realizes, nope, not hostile. He’s among them long enough to learn the language, at which point he is told that his companion is dead and that he himself has been sentenced to death for murder. When the long night comes, he’ll be left outside to freeze.

The people of Ta-tjenen call their world Patra-Bannk, which means “Freeze-Bake”. Thanks to the huge world’s slow rotation and slight inclination, days are months long and excessively hot (verging on unsurvivable), while the nights are also months long and will freeze solid anyone exposed on the surface.

Stringer tries to make friends amongst the aliens and hopes that something will intervene before he’s put out to freeze.

A scant hundred thousand kilometres away, Hendig and Pike encounter another off-worlder from Two-Bit: Paddlelack, whom Hendig had left behind on Patra-Bannk. Still vexed that Hendig marooned him, Paddlelack promptly murders Hendig. Then the whole party is captured by Gostum soldiers, whereupon an unfortunate misunderstanding occurs.

The Gostum can see that the folks from Two-Bit are an alien species and assume that Pike and Paddlelack are the fabled Polkraitz, nigh-messianic figures whom both the Gostum and the people of Ta-tjenen believe will return to save them all. Pike immediately embraces the status, the better to get the Gostum to do his bidding.

Gostum and Ta-tjenen are bitter enemies. Pike tries to ingratiate himself with the Gostum by helping them attack Ta-tjenen. Alarming enough, but contact with the vast, enigmatic entity that controls natural processes on Patra-Bannk is pushing the already over-confident Pike into megalomaniacal madness.

War comes to Patra-Bannk, pitting locals against locals, Stringer against Pike and Paddlelack. None of which addresses the true crisis facing the planet.

~oOo~

That’s a Ralph McQuarrie cover. You may be more familiar with his artwork for Star Wars or if you are of a certain vintage, the Ringworld roleplaying game.

Note re the setting: the story is set billions of years in the future, when the universe has begun to collapse on itself. The characters may act like humans, but they aren’t human. This is addressed in a short foreword.

Patra-Bannk is, of course, a vast artificial world, a hollow shell with a small black hole in the middle. It differs from many other such constructs in a number of respects, not least in that the architects of the planet had the foresight to put an artificial intelligence in charge. The AI wasn’t programmed to deal with living beings (the alien settlers are a later development) and it has had to invent novel ways to communicate. Its methods are driving Pike into madness.

Something I overlooked in 1978 was the degree to which the plot parallels the plot of Niven’s Ringworld Engineers. Like the Ringworld, Patra-Bannk has stability issues, specifically that there’s a black hole at the centre of the construct which gravity, for reasons I suspect my editor does not want me to get into at length, won’t keep centred. When things go wrong with hollow shell-worlds, problems happen fairly slowly, whereas when Ringworlds drift off centre, instability is accelerating and potentially deadly issue. Something megastructure architects should bear in mind. Both novels build up to a dramatic scene in which the instabilities are addressed. I can’t explain why I didn’t notice the parallels in 1978, unless it was the fact that Ringworld Engineers would not be published for another two years.

A large part of the inspiration for the book seems to have been the desire of the twenty-two-year-old Rothman (physics grad student, later professor) to predict the day-night cycle of a large, slow-rotating world, then maroon on it1 characters who would be forced to work out from scratch what was going on. Thus, the expedition includes no scientists. The local natural philosophers are handicapped by Patra-Bannk’s size and the fact that it orbits alone in its solar system2. There are no natural planets to observe and compare to their own artificial world.

One can tell this is a first novel (it would be a better book were it to lose a hundred pages), but it has its amusing elements, at least for fans of the humongous-world subgenre. There is the puzzle of what the world might be and why someone would have bothered to build it — not to deal with overpopulation, as the folks from Malthusian Two-Bit initially suspect, but a purpose altogether more positive3—not to mention the amusement of watching a would-be scientist struggling to comprehend a planet seemingly designed to frustrate scientific4 investigation5. Then there’s a bit of cliff-hanger: will the increasingly deranged Pike manage to massacre Stringer’s Ta-tjenen friends?

Not a classic, by any means, but not all that bad. If you run into it, it’s worth a read.

The World is Round is out of print.

1: It’s a pretty reliable rule of thumb that any group of explorers who discover a habitat larger than natural planets should pack sturdy boots because they will be forced to journey across said habitat. In this case, Stringer manages to build a glider, while the Gostum have access to a high-speed transit system that the spectacularly incurious inhabitants of Ta-tjenen never bothered to discover.

2: For example, the horizon is far enough away that ships are obscured by intervening air before they disappear over the horizon. Comparing the angle of shadows at the same time of day in different towns requires epic journeys to obtain detectable differences. And nobody has a decent clock.

3: The Two-Bit folks conclude that a species that needed to build a super-world to house a rapidly expanding population could not afford to do so, and if they did somehow manage to build such a world, exponential population growth would fill the place to capacity almost immediately.

They conclude that somewhere in the galaxy is a civilization whose member species are native to a wide variety of worlds. Patra-Bannk will someday offer a suitable habitat for each species. Whatever the nature of the civilization, it seemingly thinks nothing of million-year projects; the reason the place is so hostile is because it’s not finished.

4: As it turns out, both the Gostum and Ta-tjenan have resident natural philosophers. There’s a funny (at least to me) moment when the two enemy natural philosophers meet and get so caught up in discussing science from their respective perspectives (one focuses on pure theory and the other on experiment) that the Gostums are left to conclude that their poindexter is either dead or has turned traitor.

5: I was reminded of the Greg Egan novel Incandescence (2008). An alien genius attempts to understand the bizarre physics of his little world, which orbits a black hole.