Beyond The Moon

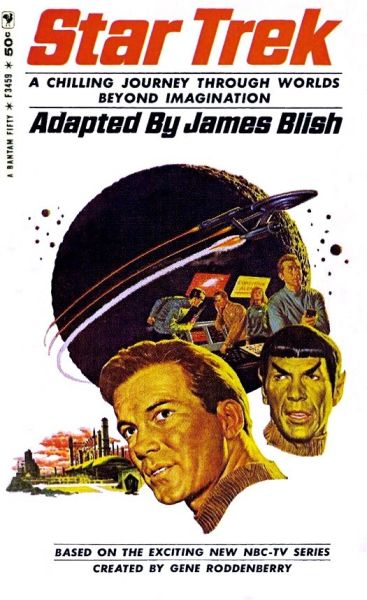

Star Trek (Star Trek Original TV Series Adaptations, volume 1)

By James Blish

18 Aug, 2024

James Blish’s 1967 Star Trek was the first of twelve volumes in the Star Trek Original TV Series Adaptations science-fiction TV-show novelizations. Later printings embraced the less misleading title Star Trek 1.

“Novelization” is a bit misleading.

Rather than devoting a full book to each episode, each volume in the series contained a number of episodes, presented as short stories. For example, the book in hand adapts seven stories (listed below).

But first! A tangent. My copy of the Bantam MMPB has long since gone missing. What I have instead is a set of the E. P. Dutton/SFBC Star Trek Readers. These omnibuses are numbered I to IV. They are eccentrically assembled. One might expect four omnibuses spanning twelve volumes to include volumes 1 to 3 in the first, 4 to 6 in the second and so on. They do not. Instead, Reader 1 includes Star Treks 2, 3, and 8; Reader II includes Star Treks 1, 4, and 9; Reader III includes 5, 6, and 7; and finally Reader IV includes Star Treks 10, 11, and the novel Spock Must Die. Star Trek 12 is omitted entirely.

As detailed in David Ketterer’s Imprisoned in a Tesseract: The Life and Work of James Blish, Blish had not seen any episodes of Star Trek when he signed the contract with Bantam. Nor does he appear to have become a fan. Why did this notoriously snobby author/critic agree to undertake hack-work, despite doubts about the project’s merits?1 Because Bantam backed a dump-truck full of money up to Blish’s home. At $2000 a book (about $20,000 per book in USD 2024), the Star Trek books offered financial security2 Blish could not turn down.

As Blish did not watch Star Trek (or at least didn’t in 1967), he worked from the teleplays. Consequently, plot details sometimes differ from the episode as it aired (as did terminology: Spock’s father’s people are referenced as “Vulcanoids”). Also, cast characterization does not appear to have gelled at this stage of the game.

As a very rough rule of thumb, a minute of screen time is about a page of script. Therefore, it’s for the best Bantam did not opt to mandate one novelization per episode, as the resulting book (even giving the much smaller page counts back in the 1960s) would have been terribly thin. Blish, by fitting each episode into 14-to-30-page stories, delivers the opposite effect; a full episode condensed down to the span between commercial breaks.

“Charlie’s Law” • [Star Trek Original TV Series Adaptations] • (1967) • Based on a teleplay by D. C. Fontanna and Gene Roddenberry

Marooned as an infant on an alien world Thasus, Charlie Evans’ survival strains belief. Charged with delivering poorly socialized Charlie to his only known relatives, the crew of the Enterprise discovers to their increasing alarm just how Charlie survived.

I happened to watch this episode over dinner. While Blish is happy to use foreshadowing, the actual episode hammers the viewer with intrusive music to signal something terrible is going on. In any case, one can’t help but feel sorry for Charlie, granted superhuman abilities without self-discipline, or any useful guidance from the crew of the Enterprise, who, whatever their strengths, are not great with teenagers.

This episode is notable for two things: Spock’s unshakable (and correct) belief that there is no way Charlie survived on his own, thus whatever the physical evidence suggests, Thasus must have natives. This establishes very early in the series that many planets have godlike natives the Federation would do well to avoid.

“Dagger of the Mind” • [Star Trek Original TV Series Adaptations] • (1967) • Based on a teleplay by S. Bar-David

Following up on the near-escape of a prisoner from a facility for the criminally insane, Kirk falls afoul of an ambitious researcher’s plan to monetize his research.

Despite Trek’s reputation as a quasi-utopia, the Federation SOP for treating prisoners and mental patients seems until recently to have been one part Devil’s Island and one part Bedlam. The side-effect of having barren worlds as oubliettes?

This too is an early example of a common Classic Trek trope: Federation functionaries left on their own easily slip into megalomania.

“The Unreal McCoy” • [Star Trek Original TV Series Adaptations] • (1967) • Based on a teleplay by George Clayton Johnson

The Enterprise visits Regulus VIII to check on archaeologist Bierce and his wife Nancy (coincidentally an old flame of Doctor McCoy’s). Everything seems fine … so why do crew keep dying?

The story notes off-handedly that the galaxy is strewn with planets littered with ruins of long-dead civilizations, a detail that would concern me a lot more than it seems to bother the crew of the Enterprise.

You may know this episode as “The Man Trap.”

“Balance of Terror” • [Star Trek Original TV Series Adaptations] • (1967) • Based on a teleplay by Paul Schneider

The warlike Romulans, about whom almost nothing is known, have been contained within the Neutral Zone for fifty years. Now the aliens may have matched or even exceeded Federation technology. Can the Enterprise prevent the Romulans from attacking the galaxy once more, or will the starship simply be another Romulan victim?

This story states that star-flight is relativistic, not FTL. Put that down to early installment weirdness. A detail that did linger is that the human crew are comfortable being dicks toward Spock on account of his alien weirdness, but there is a line past which Kirk will not allow them to pass. Yes, Spock is an off-putting pain in the ass, but nobody is permitted to question his loyalty, even though it is clear there is an undocumented connection between Vulcans and Romulans.

To Spock’s credit, when asked if the physical resemblance between Vulcans and Romulans means that their languages are mutually intelligible, he is a lot less sarcastic than I would have been in his place.

“The Naked Time” • [Star Trek Original TV Series Adaptations] • (1967) • Based on a teleplay by John D. F. Black

The Enterprise checks on a research facility, where they discover that not only is the entire staff of the facility dead, the cause of the deaths is still present and functionally contagious.

In this specific case, the Enterprise can be forgiven for assuming that the researchers would have looked for and identified environmental hazards before setting up the base… if there were any reason to think that the Federation’s main method of documenting local hazards was something other than plunking people down unprotected to see if they keel over.

“Miri” • [Star Trek Original TV Series Adaptations] • Based on a teleplay by Adrien Spies

Responding to an emergency call many decades late, the Enterprise discovers 70 Ophiuchi’s habitable world has three sorts of human inhabitants: children, deranged and weirdly aged adolescents, and corpses. The agent responsible, the product of a bungled bid for immortality, is still present, extremely contagious, and lethal to adults like Kirk and the rest of the crew.

Quarantine: It’s not a thing in the Federation. Nor are even rudimentary efforts to avoid local diseases.

Blish does explain how a signal from 70 Ophiuchi was overlooked, even though the system is right next door to the Solar System3. Still, why was the planet never visited?

The Conscience of the King • [Star Trek Original TV Series Adaptations] • (1967) • Based on a teleplay by Barry Trivors

Summoned by a report of a research breakthrough, Kirk discovers that the signal was a ruse. There is no breakthrough. There may, however, be Kodos the Executioner, who is wanted for crimes against humanity. A small handful of witnesses survive who can ID the wanted man, Kirk among them. However, someone has been murdering the remaining witnesses one by one; summoning Kirk may have made the killer’s task much easier.

Kodos is another example of a Federation functionary who went off the deep end.

1: As written in Blish’s notebooks, later quoted by Ketterer.

2: The work took more time than Blish expected. However, he was able to farm out the work to his wife Judith Blish and his mother-in-law, Muriel Lawrence, who wrote Star Trek 6 through 11 under the James Blish byline.

Blish produced five volumes (plus the Star Trek novel Spock Must Die) between 1967 and 1972. Judith Blish and Muriel Lawrence produced seven volumes between 1972 and 1977, three in 1972 alone. Additionally, Judith, writing as J. A. Lawrence, delivered the novel Mudd’s Angels, in 1978.

3: The colonists selected their emergency frequency poorly. From the Solar System’s perspective, there’s a much brighter source in line of sight with 70 Ophiuchi that drowned out the signal.