Bold Canadians

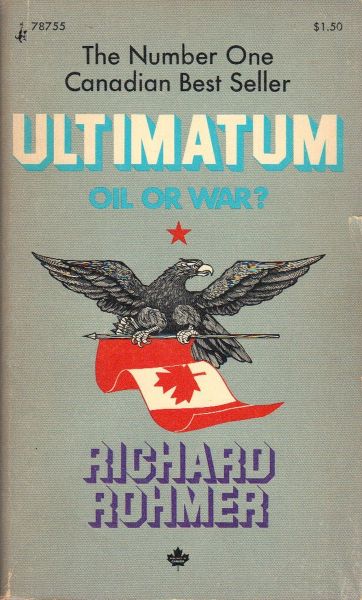

Ultimatum (Robert Porter, volume 1)

By Richard Rohmer

12 Nov, 2023

1973’s Ultimatum is the first of two Robert Porter novels by Canadian author Richard Rohmer.

Newly elected Canadian prime minister Robert Porter (party unspecified) receives a phone call from American president Howard. The Texan-born Democrat faces the challenge of reelection in just one month. He has a bold stratagem to achieve a second term, one in which Canada will play a central role.

Whether Canada wants to or not.

Relentless industrial expansion combined with the American population explosion means that American energy resources are insufficient to meet US needs. Canada could provide the US with the natural gas the US needs. For a number of reasons, Canada has been both unwilling and unable to create the preconditions necessary to satisfy the US in the matter. Therefore, the president delivers a three-point ultimatum (in this order):

- Canada must, as the US did, recognize aboriginal rights and reach an equitable arrangement with native groups concerning fossil fuel extraction and sales.

- Canada will give the US full access to Arctic Island natural gas without concern for Canadian needs.

- Canada will permit the US to create the infrastructure to transport natural gas from the North to the US.

The deadline is 6 PM the following evening. The US has many means to bring Canada to heel, demonstrated by the president’s preemptive embargo of US investment in Canada. Result: an immediate $30-million-dollar-a-day hole in the economy.

With little time to act, the prime minister orchestrates an emergency meeting of parliament, summoning together his own party, the opposition1, the New Democratic Party, and the Social Credit Party. Although Canadian politicians are, to a person a stalwart lot who, despite policy differences, uniformly agree that national interests must come before party loyalty, the current crisis may be beyond their combined skills.

While the American president takes a sudden northern tour so that he can survey and discuss in great detail the resources of the North, the dismal infrastructure in that region, and the bold technological advances that could deliver cheap gas to the US, the Canadians consider their options and orchestrate a response. As one would expect from a prime minister, Porter confers with the press to avoid panic2 and conscientiously consults a broad cross-section of national leaders, even those of provinces that legally have little say in this matter3.

Canada does have some cards to play and it does. Will this satisfy the American president? Or will it simply provoke a more extreme reaction from a man determined to keep his job?

~oOo~

A note about terminology: usage regarding First Nations has changed since this book was published.

With his hundredth birthday only three months away, Richard Rohmer has had a colorful and very long career, of which writing best-sellers is a very small part. However, everything but his ludicrous pot-boilers fall outside the concerns of this site. He was in his day an extremely popular Canadian author. Rereading this novel, one has to wonder how few home-grown books there must have been for this one to have been so popular. It was the best-selling Canadian novel in 1973; it was found in every school library.

A major issue with the novel, although perhaps one that won’t bother all the Poul Anderson fans out there, is that a huge fraction of the book consists of infodumps about the resources of the far north and the new technologies that could make them accessible4. (Exploiting the North just happened to be one of the goals of Rohmer’s political career.) The American president’s sudden tour of the North exists purely to justify these infodumps.

Also, by the nature of the plot, a considerable fraction of the remainder is people talking to each other at great length. It turns out that parliamentary democracy involves extensive polite debates and private conversations. Arguably better than resolving differences by hurling people through windows but it’s not very dramatic, particularly given politician characters who are apparently addicted to reasonable consensus.

Finally, the prose is serviceable at best. Again, not necessarily a problem for fans of SF pulps, but don’t go into this expecting James Joyce. Or even Farley Mowatt.

There are some points of interest. For example, anyone curious about the state of northern resource exploitation fifty years ago will enjoy the American president’s tour of the North.

While Rohmer is clearly a Canadian nationalist, at no point does the American president empty a pistol into a crowd of cheerleaders, propose ethnic cleansing, or eat a live baby. The president is an antagonist but not a villain as such. The plot point that he prioritizes First Nation discontent may suggest that Rohmer’s model is Lyndon Johnson, circa the Civil Rights Act.

Furthermore, Canadians are not entirely the paragons of virtue suggested by the summary. The situation with disgruntled natives is entirely of Canadian manufacture, as is the issue with native terrorists, (because all other ways of getting federal attention were rejected). As well, the passing presentation of residential schools is more negative than I’d have expected from a white Canadian born in 1924, writing in the early 1970s. Our bureaucracies are acknowledged as onerous.

Nevertheless, Ultimatum is not great literature and the emphasis on discussion means that while the stakes are high, it’s not much of thriller. At least for me. Canadian ate this book up fifty years ago. Who knows? Perhaps I overlook certain virtues.

Ultimatum is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Apple Books), here (Barnes & Noble), and here (Chapters-Indigo). I suffered through it as a teen and now you can too!

1: I only notice on this rereading that the author is very careful to avoid any mention by name of the Liberals or the Progressive Conservatives, allowing readers to think the party they most supported was governing. Saying otherwise would upset some readers. Since neither the NDP nor SoCred have a realistic chance of forming a government, it’s safe to name them.

The text suggests that the PM has a plurality but falls one seat short of a majority, while to form a majority all other three parties would have form a coalition. This may explain why the PM is so careful to consult with parliament; he can afford to anger any two parties but not all three. It’s also consistent with the text that the PM is a living windsock who will not act until he measures public sentiment.

The now long-vanished Social Credit Party (circa 1970) is responsible for my favourite political slogan of all time:

“Ladies and gentlemen, the Union Nationale has brought you to the edge of the abyss. With Social Credit, you will take one step forward.”

2: Rohmer namechecks the Global TV network, which I thought didn’t go live until the year after the book was published. I am reading the ebook omnibus so he could have updated the text, but other details suggest he didn’t.

3: A quotation from the Albertan Premier that suggests this is the product of a different era:

But let me tell you that we are Canadians first, and Albertans second.

In general, even when they disagree strongly with each other, the Canadian politicians in this novel respect each other and seek ways to cooperate. Therefore, I do not hesitate to classify this as science fiction or possibly fantasy.

4: Including one odd notion that I was astonished to discover was seriously proposed: the Boeing Resource Carrier 1, a cargo plane able to transport 1000 tons of cargo sixteen hundred kilometers. It was intended to be used in lieu of pipelines.