CanLit meets SF

In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination

By Margaret Atwood

4 May, 2015

0 comments

In the world of Canadian literature, Margaret Atwood is revered as a major figure, a giant who towers above such lesser authors as Alice Munro, Michael Ondaatje, Anne-Marie MacDonald, and Margaret Laurence — who even stands far above such revered past masters of Canadian authorship as Alistair MacLeod and Robertson Davies [1]. Well, if the world of Canadian literature is defined as me.

Alas, despite the fact that at least three of her books—The Handmaid’s Tale, Oryx and Crake, and The Year of the Flood—are indisputably science fiction, her relationship with the science fiction community is somewhat, shall we say, fraught. In large part this is because she denies that her books are science fiction at all. The uninformed perception is that she is hostile to science fiction, which feeds into the whole perception that litfic types disdain and mock science fiction. I believe that this canard goes back to that time Ernest Hemingway gave Robert Heinlein a thumping and then took his lunch money [2].

This is unfair and untrue. Proof of that assertion exists in the form of Atwood’s 2011 collection of essays and other work, In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination. Her text isn’t intended as a general work on science fiction as a whole, but rather as an exploration of Atwood’s personal relationship to science fiction.

Part of the discord between Atwood and the science fiction community is that Atwood insists on using her own, very personal definitions; what she means by science fiction is much more specific than the definition used by most people (or at least by me). She’s aware that her definitions are peculiar to her, having compared notes with Le Guin. What Atwood calls science fiction might map onto what other people call fantasy and what she calls speculative fiction might map onto science fiction.

I. In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination

Before my parents immigrated to Canada in the 1950s, much of Canada was a rural backwater [3]; small urban populations were surrounded by loggers, farmers, fishers, hunters, and miners, who were in turn surrounded by intermittently habitable desolation. A child of the Depression era, Atwood appears to have grown up in an extremely isolated part of the country, without easy access to films or radio (a bit odd, because the CBC Radio was around back then). But she did have books and she did have comics. As amazing as it may seem to readers who are more familiar with her high-brow books, she had a strong taste for fantastic fiction of the most lurid and colourful sort, even creating her own comic book heroes.

Throughout this chapter, Atwood ties her personal favourites into grander themes, almost as though passage through a university career shapes the language and cognitive tools one uses to reexamine old favourites.

Comments:

This is an interesting chapter and not just because, rather like Robertson Davies’ biography, it really highlights how primitive Canada was within living memory. While Atwood doesn’t seem to have found the Astounding end of fantastic fiction interesting, she read and comments knowledgeably on material that ranges from H. Rider Haggard to various comic books.

Unfortunately, it’s a bit marred by the fact that Atwood relies entirely on her own memory without double-checking certain facts; she conflates Captain Marvel with Captain Marvel, Jr.. Don’t look at me like that. It’s my job to know things like that.

Drawing on the work of critics like Northrop Frye and Marshall McLuhan, Atwood discusses the shape of the modern fantastic and why it is it takes the forms that it does today. The decline of superstition has transmogrified themes that would have been turned into myth in previous times, into fantastic stories set on imagined worlds in space.

Comments:

The whole process of the fantastic migrating from myth to commercially imagined worlds is paralleled, I think, by the way as we learned more about the solar system, SF authors were forced to move their stories from now mundane planets out into the stars. This seems like a perfect place to reference certain Bradbury stories … but I am not going to.

Atwood looks at utopias and their mirror image dystopias, drawing examples from literature (including her own work). Atwood also speculates why it is that utopias have fallen out of fashion while dystopias are increasingly popular. She notes that it cannot have helped the cause of utopianism that such utopian schemes as communism and fascism underperformed when applied in the real world.

Atwood talks at some length about her educational background and personal aspirations. Of particular interest is her never finished PhD thesis, “The English Metaphysical Romance,” which focused on female figures in the fantastic. It seems to have been at least in part an experiment to see if she could earn her PhD while reading lurid old favourites like She.

Comments:

The title of this makes me curious if Atwood has read Hell’s Cartographers.

“Ustopia” is an Atwoodism that includes both utopias and dystopias (and I would think given how often “dystopia” has been mentioned in my reviews over the years, my dictionary would have come to accept it as a real word). I am not entirely certain why she feels that there needs to be a single term but it seems very Atwoodian that she would make up her own word.

I find it interesting that, while Atwood is knowledgeable about modern SF, there’s an odd disconnect between the subset of modern SF she reads (names like Butler, Lem and Le Guin are mentioned) and the older, rather pulpish fantastic fiction she of which she is still fond (Kipling and Haggard, for example). IMHO, there are many modern authors I would expect her to like of whom she seems to be completely unaware. I am very curious how she would react if someone were to send her a box of books by Piper, Bujold, and Carey.

II. Other Deliberations

This is a collection of Atwood’s reviews of various works of speculative fiction. Reviewing reviews seems a little meta. On the whole while Atwood’s perspective is from an angle unfamiliar to me, her competence cannot be denied.

Atwood examines this as a utopian novel rather than a naturalistic novel about a mad woman.

Comments:

Atwood has certain, hmmm, middle class Canadian of a particular era assumptions about how the world works. In other chapters this emerges as a tendency to use “man” to include men and women. Here it takes the form of making a case that Connie’s visions had to be more than hallucinations because Connie “isn’t educated enough to have such a utopian vision.”

Drawing on her knowledge of the period when Haggard was writing, Atwood discusses this famous work of adventure, focusing in particular on why She was the sort of character that She was.

This is a somewhat detailed review and discussion of this comparatively recent UKLG collection, placing it in the greater context of Le Guin’s career and the specific context of the early 21st century.

In the course of reviewing a book denouncing modern technology, Atwood more or less agrees with the author’s thesis that humans have or are about to go TOO FAR!

Comments:

It is because of people like Atwood I cannot purchase a nuclear-powered exoskeleton enabling me to crush people’s skulls like eggshells.

Drawing on her personal experiences of reading Orwell (and on her own fiction), Atwood discusses Orwell’s two best-known books: Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty Four.

Comments:

Atwood read Animal Farm as a child, expecting it to be the usual sort of children’s talking animal book.

To say I was horrified would be an understatement.

Suddenly, I have some new Christmas gift ideas concerning my young grand-nephew.

This is exactly what it says on the tin.

A review of Ishiguru’s novel.

Comments:

Own it, still haven’t read it. I did read his Arthurian novel, though.

A review of Bryher’s work, with details of the author’s life.

Comments:

It’s unfair to Bryher that reading this review made me think of When the Kissing Had to Stop, so I think I am obligated to track down a copy of Visa for Avalon to read for myself.

A review of Huxley’s book, with lamentations about the modern human condition included free of charge.

• Of the Madness of Mad Scientists: Johnathan Swift’s Grand Academy

Using Swift’s work as a springboard, Atwood discusses how scientists have been depicted in fiction.

III. Five Tributes

In which the author admits to having sometimes committed flagrant works of science fiction and then very considerately provides evidence.

A discussion of cryogenics as a meaning of escaping from the Current Unpleasantness (and there’s always a Current Unpleasantness). The cryogenics advocate is less than pleased at the eagerness with which his friends poke holes in the idea.

Comments:

While leaping into the future with cryogenics appears like a good idea, there is nothing to stop the cryogenics company from taking your money and then arranging a power outage to justify dumping the remains. I could name examples.

Aliens examine humans and are not much impressed. They look forward to the day when they can inherit the Earth after our own self-inflicted demise.

An entity describes itself in unconventional terms.

Progress led a race to lay waste to its own world. Pursuit of wealth brought only extinction.

Comments:

It seems to me if Atwood had not grown up out in the uncharted wilderness of pre-Nicoll Canada and if she had not then been seduced by the unsavoury world of higher education and Can-lit, she might have had a perfectly respectable career selling short tales of speculative fiction to editors like Anthony Boucher, Ed Ferman, and Fred Pohl. She might even have been featured on X Minus One and Mindwebs (or perhaps relegated to later Canadian radio shows like Vanishing Point and Nightfall; I should probably check to see if Atwood was on either of the latter two in real life but I am not going to do so).

Two astronauts find a world of exotic women, a world that may be a trap. Comes with some discussion of the story by its fictional pulp-era author and his girlfriend.

Appendices

Atwood deals with the JISD’s hostility towards her novel The Handmaid’s Tale. It begins

First, I would like to thank those who have dedicated themselves so energetically to the banning of my novel The Handmaid’s Tale. It’s encouraging to know the written word is still taken so seriously.

and builds from there.

Comments:

On the whole I would not recommend getting into a war of words with an author. Even the knuckle-draggers from Baen, hampered as they are with a general lack of skill and insight, are well armed with exuberant prolixity.

Margaret Atwood discourses knowledgeably on the art and context of Margaret Brundage, noted cover artist for Weird Tales.

Some of you may be unfamiliar with Brundage’s work. Enjoy!

Comments:

I first read In Other Worlds in manuscript form in 2011. The MS was missing the appendices and any indication of what was in them. Even after reading the rest of the book, I probably would have been willing to place long odds against ever needing to type “Margaret Atwood discourses knowledgeably on the art and context of Margaret Brundage […]”. And I would have been wrong. If I’d ever read Atwood’s The Blind Assassin, I would not have been as surprised as I was last night when I encountered this — but I didn’t and I was.

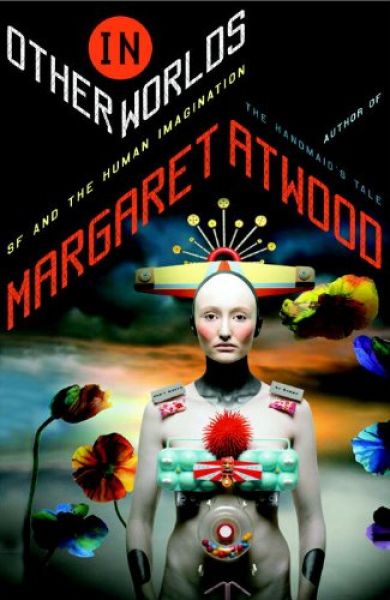

Was Anchor trying for a Brundage vibe with their cover?

~oOo~

Comments FOR THE BOOK AS A WHOLE:

Bad stuff first: this does not have an index. IT DOES NOT HAVE AN INDEX. IT’S THE 21st CENTURY, PEOPLE. NON-FICTION HAS TO HAVE AN INDEX. THERE IS NO EXCUSE FOR NOT HAVING AN INDEX.

Also, I am not 100% keen on the cover, although it certainly is evocative of a certain era in SF book covers (oddly enough, probably not an era in which Atwood seems widely read).

This is a fairly idiosyncratic discussion (or rather, collection of loosely related discussions) of speculative fiction. While there were one or two spots where I wish she’d had someone glance at the MS, she’s generally not misinformed. While some people might asset that Atwood is interrogating the material from the wrong perspective, I don’t think that’s the case. I think her perspective is just one unfamiliar to me.

I do wonder how Atwood would react to that hypothetical box of competent mainstream science fiction.

1: I assume I don’t need links for all those authors?

2: I assume. Actually, I did come across what I think may be the ur-example of a mainstream critic sneering at science fiction but do you think I can find it?

3: For example, the innovative design of CANDU reactors was driven by the fact Canadian industry wasn’t up to duplicating large pressure vessels.