Dear Old Dixie

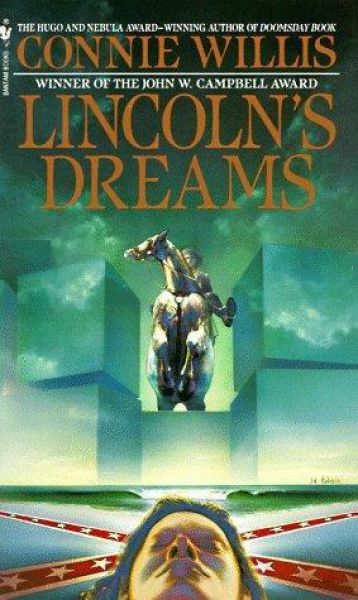

Lincoln’s Dreams

By Connie Willis

21 Dec, 2023

Connie Willis’ 1987 Lincoln’s Dreams is a standalone contemporary speculative fiction novel.

Jeff Johnson works as a researcher for historical novelist Broun. His job is to run down answers to questions, some questions significant and some trivial. Broun is an enthusiastic over-thinker and compulsively tinkers with manuscripts already in galley form. Which means that the novelist keeps Jeff busy tracking down historical minutiae. It’s too bad that Jeff is really not all that informed about the history he is researching. This makes his job difficult and his hours long. He doesn’t need any distractions.

But he’s distracted by troubled Annie and her perplexing dreams.

Annie is the girlfriend of Jeff’s college roommate. Annie’s dreams are odd because they seem to be someone else’s dreams. When she sleeps, she relives scenes from the American Civil War1. From whose perspective is she reliving the past, and why is she reliving the past?

Her boyfriend, a doctor at a sleep institute, sees the dreams as evidence of a delicate mental state. He’s not interested in them; he just wants Annie to stop dreaming. Annie thinks there’s more to her dreams than that and asks Jeff to help her unravel the mystery of her dreams. Are they visions of a real past?

Jeff and Annie discover that she is not reliving Abraham Lincoln’s dreams (despite the title of the novel). Rather, the source of the dreams appears to be Robert E. Lee. Why would a dead Confederate general single out a seemingly unremarkable 20th century woman to bombard with visions of the past?

Author Willis is known for novels in which incompetence and miscommunication do overtime as plot facilitators. Given that authorial tendency, is there any hope that the characters will work out what’s going on before it is too late?

~oOo~

Readers unfamiliar with Connie Willis’ early work may be surprised by how slender this novel is. At just over 200 pages, it’s almost a novella compared to novels like To Say Nothing of the Dog (400+ pages), Passage (~600 pages), or Blackout/All Clear (1,100+ pages). Nevertheless, the fans who have voted Willis award after award need not fear that this is an atypical work. Every Willis quirk is on display here, including the painstaking attention to historical detail that led to a character in Blackout/All Clear using the Jubilee Line decades before it was built.

The key to writing short novels is to leave words out. Generally speaking, the more words that are in a novel, the longer it’s going to be. Unfortunately, Willis left a few too many words out, leaving the novel with a gaping hole at its centre.

Jeff appears perplexed by the causes of the American Civil War. How was it that two peerless stalwarts like Lincoln and Lee found themselves on opposite sides? How is it the American Civil War happened at all? Jeff struggles to understand this inexplicable, seemingly causeless event.

Jeff’s perplexity can be traced back to some words Willis left out. Nowhere in the novel will one find the words “slave,” “slavery,” “black” (save as a color of blisters, objects and animals), African (save in reference to violets), “Negro,” or “abolition”2. It’s no wonder that the American Civil War is a such a puzzle to Jeff. The author having omitted the central cause of the American Civil War, slavery, of course the conflict appears to be bafflingly spontaneous.

One can never be sure why authors write what they do. I think that we can rule out the conjecture that Willis had never heard of African Americans. By 1987, I think most white Americans had some vague awareness that Americans of African origin existed. Willis’ native Colorado seems to pretty white, but it’s not Vermont white. It doesn’t seem possible that she was so sheltered as to not have ever heard of African Americans.

I think more likely the culprit is the author’s desire for a false equivalence between Lee and Lincoln as equally tragic heroes of the American Civil War. Lee’s cause was the slavers’ supposed right to own other people, a cause for which he sent many young people off to die (in a war in which the South fired the opening shot). Lincoln also sent a lot of soldiers off to die, but he was responding to Southern aggression and was of course an abolitionist. The only way to make Lee and Lincoln seem mirror images is to willfully erase the issue (and the people at the centre of that issue) that divided them. Thus, the bizarre phenomenon of an American Civil War novel that entirely omits the causes of the American Civil War. I cannot say if this is a dishonest novel or merely fearfully ignorant.

The issues that vex me did not vex other people back in 1987. The book won accolades from Twilight Zone Magazine, Fantasy Review, Publishers Weekly, Harlan Ellison, Richard Adams, and Michael Bishop.

Aside from the small matter of a narrative seemingly crafted to appeal to Lost Causers, the book has many of the qualities of a novel. There are characters, some of whom are rather shallow. The prose is acceptable. There is a medical malpractice plot imbued with entrenched misogyny that I wish had been the actual focus of the work. Best of all, the novel is very short.

Lincoln’s Dreams is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Apple Books), here (Barnes & Noble). and here (Chapters-Indigo).

1: Yes, I will use American Civil War each time, to distinguish it from all the other civil wars.

2: ‘Color’ and ‘colored’ are likewise absent as labels for people, which is for the best.