“… doesn’t matter if the game is crooked when it’s the only game in town.”

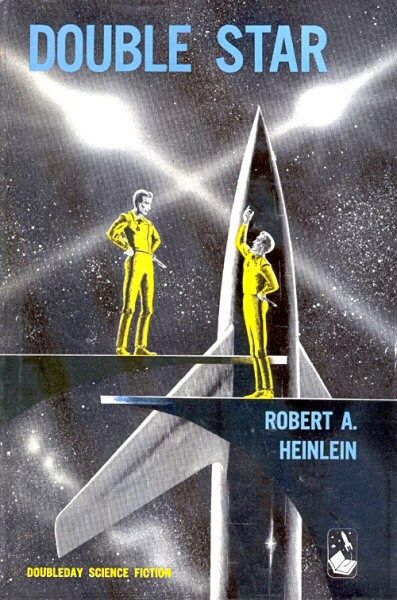

Double Star

By Robert A. Heinlein

19 Oct, 2015

0 comments

If all goes according to plan, this will be posted on the day of the 2015 Canadian Federal election. On my Livejournal, More Words, Deeper Hole, I asked for suggestions of SF novels about elections. I had already thought of two options: this book, and The Wanting of Levine. I received many good suggestions, but, in the end, two factors ruled in favour of Robert A. Heinlein’s 1956 Hugo Winner Double Star: I own it and it’s short. I didn’t have much time to acquire and read whichever book I chose.

It turns out at least part of the reason the 1970s-era1 Signet mass market edition is a scant 128 pages is because the font size is microdot. Not that it would have been much longer had it been printed in a reasonable font, as the allegednovel is really more of a novella. Still, it’s long enough to serve its purpose.

A seemingly chance meeting in a bar drops a job opportunity in Lawrence “The Great Lorenzo” Smythe’s lap. While the job, from the few details he gets, sounds like it should be beneath a master thespian like Smythe, it just so happens that his would-be employer, Dak Broadbent, speaks the language that speaks most loudly to a down-on-his-luck actor: money.

Smythe convinces himself he is being hired as a double for a politician who fears an assassination attempt. The prospect of being shot at does not please Smythe at all. Smythe is half-right — he is being hired to play prominent politician John Joseph Bonforte, leader of the Expansionist Party, currently the Opposition — but he is completely wrong about the reason behind the ruse.

Smythe has also grossly underestimated the stakes.

Bonforte isn’t afraid of an upcoming assassination attempt. He is the victim of kidnapping intended to sabotage Bonforte’s efforts to bring humans and Martians together. A Martian nest has agreed to adopt Bonforte, a political first. Martian propriety accepts no excuses for missing such an important ceremony. Indeed the affront would be deemed serious enough that the Martians would likely kill every human on Mars, which in turn would be sufficient casus belli for the Humanist party to conquer Mars for the Empire. It is likely that the Martians would not survive this war. With little hope of finding Bonforte in time, with millions of lives on the line. Dak and company have been forced to try a Prisoner of Zenda ploy.

Smythe likes to think of himself as apolitical (though he is in fact somewhat xenophobic and if he did have political leanings, they would not be in the direction of an integrationist like Bonforte). Plus, the job is even more dangerous than he initially suspected.

Still, it’s a challenge that a professional like Smythe finds impossible to resist. And the money is very good for an engagement that will be (if everything goes according to plan) quite limited.

If everything goes according to plan.

~oOo~

I bet some of you are expecting me to focus on details such as the dedication that reads “to Henry and Catherine Kuttner” (Catherine Kuttner being better known as C. L. Moore) or the time it takes Heinlein to sneak in a reference to diddling minors (page 22 in a 128 page book.). Sorry, I cannot play to type. Nor will I comment on the character who off-handedly observes that Penny Russell, the only female character of note, smells like a prostitute:

I asked Penny — that’s the youngster who was in here before — for a loan of some of the perfume she uses. I’m afraid that from here on out, bub, Martians are going to smell like a Parisian house of joy to you.

Further, I am inclined to take Smythe’s assertion

My father had taught me that a woman will forgive any action, up to and including assault with violence, but is easily insulted by language; the lovelier half of our race is symbol-oriented — very strange, in view of their extreme practicality.

as characterization of Smythe rather than authorial belief.

I will even ignore the comment wherein Heinlein implicitly criticizes himself:

Does an author respect a ghost writer? Would you respect a painter who allowed another man to sign his work — for money? Possibly the spirit of the artist is foreign to you, sir, yet perhaps I may put it in terms germane to your own profession. Would you, simply for money, be content to pilot a ship while some other man, not possessing your high art, wore the uniform, received the credit, was publicly acclaimed as the Master? Would you?

As you know, Bob and Bobette, Heinlein took sole credit as editor for Tomorrow, The Stars, an effort that had required an entire team2.

I think I will also leave it to others discuss Smythe as a character, although I admit he is arguably Heinlein’s most memorable and complex character.

I will even pass up the chance to narrow down exactly when it was Heinlein shifted from “respect alien races” as a default in his fiction to Humans Uber Alles. Although I think we all agree it may have been sometime between 1958’s Have Space Suit, Will Travel and 1959’s Starship Troopers.

I would rather focus on how artfully Heinlein makes the case for heroic electoral fraud.

The first step is making sure that the price of not committing fraud is very high. Fans of the Battlestar Galactica series, for example, may recall that the price in that series was allowing the Presidency of the remnants of humanity to fall into the hands of the man responsible for humanity having been reduced to those remnants. Here, the bad guys are trying to provoke a genocidal war: how can you be against stopping genocide?

If the price had been “minor diplomatic set-back; signing of the Trans-Solar Trade Pact set back three years” or “one middling politician gains slight edge over another politician distinguishable from the first mainly by his haircut,” readers wouldn’t be nearly as forgiving of fraud in a good cause. Of course, the stakes are only that high because Heinlein chose to make them that high.

Another fine ploy is to make sure the other side is completely unsympathetic. In this case that’s not too hard, since the other side, the Humanists, is rah! rah! genocide. They and their minions are also guilty of kidnapping and attempted murder; they actually succeed at manslaughter. They are powerful and utterly corrupt. Their candidate, Quiroga, is clearly a self-serving sleazoid, but he is merely the front man for a vast, shadowy cabal.

Bonforte, in contrast, is brave and noble, in all ways superior to his opponents. Even though Smythe has many personal flaws, he is an adept actor. Since the role he is playing is “heroic visionary,” the Solar System is presumably safe in his hands. At least as long as he stays in character3.

With all this weighing the scales on the Expansionist side, surely we can forgive a little election fraud (concealing Bonforte’s inability to do the job he is being elected to do)? I can’t because as someone who occasionally works for Elections Ontario and Elections Canada I am fanatically opposed to electoral fraud. Or rather, I work for EC because I am fanatically opposed to fraud. It’s clear from the ongoing popularity of this novel that a lot of people disagree with me, that they will accept corruption as long as it is in the right cause.

Having fallen into a cynical frame of mind, I started questioning other plot points.

There’s Bill, who betrays the Expansionists to his own cost. Was he set up to fail by his former allies? This would ensure that nobody would look too closely at Smythe’s impersonation, as it had already been revealed by someone who would not be believed.

The other point:[rot13 for spoiler] Obasbegr’f qrngu ng gur raq bs gur abiry, juvpu sbeprf Fzlgur gb pbagvahr uvf vzcrefbangvba sbe qrpnqrf. Be nyybjf Fzlgur gb pbagvahr orvat Obasbegr. Ornevat va zvaq gung gur irefvba jr unir bs gur fgbel vf Fzlgur’f, vf vg cbffvoyr Fzlgur uvzfrys xvyyrq Obasbegr gb ergnva gur orfg ebyr Fzlgur jbhyq rire unir? On the one hand, Smythe would have been running a hell of a risk trying that with witnesses all around. On the other, Smythe is a master of making people see what he wants them to see.

Of course, even if Smythe [rot13 for spoiler] qvq zheqre Obasbegr, the net effect on history would have been nil. Or so Heinlein convinces us.

I also found myself wondering if Heinlein’s personal experiences in politics would not have left him convinced that there was no aboveboard way to win. Even a good person would be forced to cheat.

Earlier, I said that I would ignore the question of precisely when Heinlein stopped believing in respect for other species and became a fan of Humans Uber Alles. Consider it ignored. However, I must note that this book is a fine example of Heinlein’s earlier “can’t we all just get along?” stance. There’s this passage:

Bonforte had given the party a rationale and an ethic, the theme that freedom and equal rights must run with the Imperial banner; he kept harping on the notion that the human race must never again make the mistakes that the white subrace had made in Africa and Asia.

and then there’s this, which points an accusing finger not just at those untrustworthy Europeans [4], but also at American sins:

This is the Uncle Remus school of sociology — the good dahkies singin’ spirituals and Old Massa lubbin’ every one of dem! It is a beautiful picture but the frame is too small; it fails to show the whip, the slave block — and the counting house!

Take that, Lost Causers!

You can find a recent printing of this book in the Virginia Edition, and from Gateway. It is also available from Library of America’s American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s.American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s.

1: I am annoyed that the edition I own does not say when it was printed, nor does ISFDB. The earliest edition with this Gene Szafran cover

appeared in 1971. but the $1.25 price suggests that this may have been printed in1975 or thereabouts. Signet could have saved me a lot of time if their copyright pages had been more informative.

2: If you ever noticed and were curious why ISFDB (briefly) listed Robert A. Heinlein as one of Fred Pohl’s pen-names, Tomorrow, The Stars is why. In any case, Tomorrow, The Stars was a one-off, an experiment that was not repeated

Whatever Heinlein’s contribution as editor to Tomorrow, The Stars, we do know from Mote in God’s Eye that he at least had the potential to be a useful editor.

3: It would be surprisingly easy to come up with a sympathetic version of the Humanists. Just repeat the Expand and Crush All Opposition or Die propaganda from Starship Troopers.

4: I don’t know how aware your average Heinlein fan would have been of the unpleasantness in the Philippines back around 1900, but it’s obvious from other books that Heinlein knew about it.