Don’t Fear the Reaper

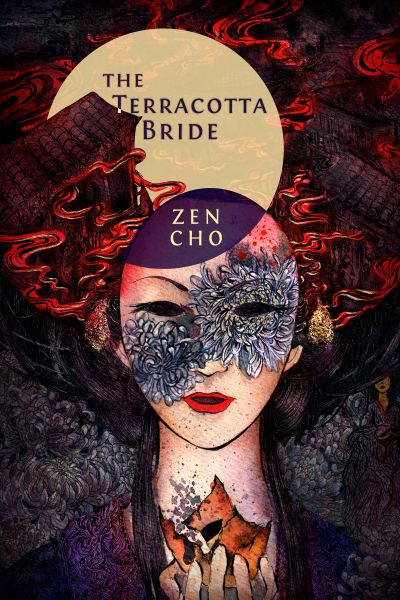

The Terracotta Bride

By Zen Cho

22 Mar, 2016

0 comments

My main complaint about Zen Cho is that she doesn’t publish as much and as often as I would like1. Still, not only can I gleefully anticipate the second Sorcerer Royal book, but 2016’s The Terracotta Bride has just been released. And just purchased by me.

You might think death is the end to all of life’s problems. If you do, then some day you will discover, as did the unfortunate Siew Tsin, that this is not at all true.

Educated by nuns, Siew Tsin might have expected the afterlife to feature wings, harps, and much singing, performed on fluffy white clouds. What she got was a world filled with officious, unpleasant demons, where the souls of the dead are prepared for their next life by having their past sins beaten out of them. But because the demons are as corrupt as any human, it is also a world where the lucky few can buy their way out of punishment.

Siew Tsin, run down by a car before her life had really begun, is not one of the lucky few [2]. She doesn’t even have a reliable protector; her Fourth Great-Uncle is worse than useless. In the end, she is sold to the wealthy but foolish Junsheng, who fancies her as a second wife.

Life as a second wife is better than being tortured by demons, but it’s not exactly fun. Junsheng is as fickle he is inconsiderate. One day, Siew Tsin discovers that she has been displaced in Junsheng’s consideration. There is a new woman in the household: Yonghua, “the elegant lady.”

Yonghua is no woman of flesh. She’s something new: she has been formed from durable terracotta. Junsheng sees her as a prize, proof of his pre-eminence. For Siew Tsin, she is something else. (You might be thinking “rival.” Maybe, maybe not. I’m not going to spoil this for you.)

~oOo~

At least Siew Tsin has been exposed to Chinese beliefs about the afterlife. If everyone on the planet ends up there, it must come as a rude shock to many of them.

Yonghua appears to be a mere mechanism, but she can learn as people do. She might not have had a soul when she was made … but it seems as if she has developed one. It is thus arguable that this is science fiction, despite the fantasy trappings. After all, what drives the story but a novel technology that changes society?

Not just society. If souls can be housed in durable, potentially immortal bodies, what happens to the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth? The novelette spends some time discussing this issue.

Think, Ling’en had told her, what could you do with a thing that resembled a human body? Stronger than a human, more beautiful, and most importantly — immortal. Impervious to illness and the persecutions of demons alike. Such a thing was not pinned to the spokes of the Wheel, unlike the bodies of every natural thing. Rebirth did not apply to it.

And

“But this man or woman, whoever it was who created our Yonghua — they asked themselves: what if we could transfer our consciousness into something that is not vulnerable to the demands of the Wheel? If there was something like that, it would render the idea of past lives and future lives obsolete. All lives would become one.”

“They want to become Buddhas?” said Siew Tsin.

“Without putting in the work,” said Ling’en. “There is a group claiming that they have found the secret of immortality. They have worked out a way to insert their minds into an immortal shell that does not need food or air to live, that is not affected by material things the way humans are.

“Once a person has locked their consciousness into this shell, their memories are sealed in with them forever. Even if the shell drank Lady Meng’s tea of forgetfulness, the mind would be untouched. The person could climb up into the living world again and live as themselves forever. They say to live in this shell is like being human, but even better.”

I bet Yonghua’s creators have overlooked some very important details. But that’s not what the story is really about, because Yonghua isn’t the protagonist. Siew Tsin is. Nor is it about the obvious philosophical implications of Yonghua’s existence — though it does spend a fair bit of time on the secondary implications, effects of that Yonghua’s designers likely never considered3. Which is one of the elements that makes this story straightforward hard SF, even though it is set in a supernatural afterlife4.

I didn’t pay enough attention when I bought this. It is clearly labelled as a novelette, but I expected a short novel. I settled down for a satisfying read and then — zoom — it was over. This doesn’t mean that I thought it a bad novelette; it is just as long as it needs to be and no longer, which is good.

Also, I now know that this first appeared in Torquere Press’s Steampowered 2: More Lesbian Steampunk, which suggests that the whole collection is worth a look. So the purchase was not an error on my part, but a necessary step towards another (possibly) pleasant experience.

The Terracotta Bride is available here.

1: And that she wrote more SF, rather than fantasy. Oh, well. I choose to regard this as an excellent addition to her corpus of good SF.

2: One attains riches in the afterlife if one has devoted relatives who burn paper money/cars/houses, etc., which translate into real wealth for the deceased.

3. As someone or other once said, the trick isn’t predicting the automobile, it’s predicting how its existence will change courting customs.

4: Thoughtful consideration has led me to decide that romance, involving as it does the highly complex interaction of human neurochemisty with cultural and technological factors, is hard SF. Very hard SF because romance is especially difficult to mentally simulate accurately, not easy-peasy like rocket science.

Romance as hard SF may seem counterintuitive, but it’s the counterintuitive results of modeling that are often the most interesting outcomes.