Drawn in the Snow

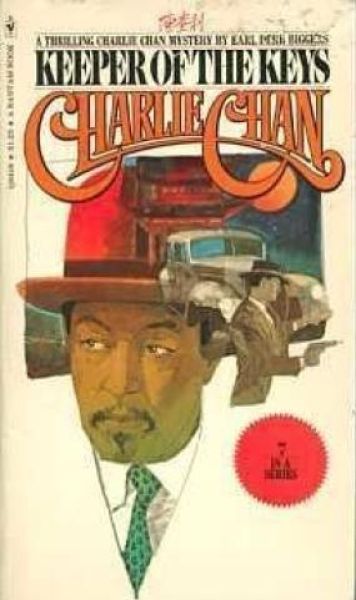

Keeper of the Keys (Charlie Chan, book 6)

By Earl Derr Biggers

7 Jul, 2024

Earl Derr Biggers’ Keeper of the Keys is the sixth and final Charlie Chan mystery.

Inspector Charlie Chan takes leave of mundane Honolulu and travels to exotic Truckee, California. There Chan hopes to finally see snow close up, rather than at a distance1.

Chan will get his snow. He will also get the chance to solve yet another murder.

Chan arrives at host Dudley Ward’s home to find himself in the midst of an impromptu convocation. The common achievement celebrated by Ward, John Ryder, Dr. Frederic Swan, and Luis Romano? All are or soon will be ex-husbands of famed singer Ellen Landini. While the men are not exactly chums, particularly with their immediate successors, they do agree that Ellen is both irresistible and vexing. To complete the experience, Ellen is also present, having come to get divorced in nearby Reno.

Chan himself was never married to Ellen. Ward invited Chan for his investigatory talents. Ward belatedly discovered that Ellen had born a son soon after leaving Ward. She kept this a close secret, presumably for professional reasons. Ward is eager to know what happened to the boy, thus the presence of a detective and everyone who might have clues to the boy’s whereabouts.

The obvious person to ask is, of course, Ellen herself. Before Chan can ask, someone shoots and kills Ellen. Now Chan is not only faced with a quest to find a missing boy, he must also solve the murder.

Suspects abound. However, to many people’s intense distress, the person who most frequently appears as a person of interest is Ward’s aged Chinese servant Ah Sing. That the universally beloved Ah Sing could be a killer is as unthinkable to the household as it is to the sheriff of nearby Truckee… and yet that is where the clues point.

~oOo~

I recently read articles revealing that Chan was inspired by real-life Honolulu detective Chang Apana. The articles gave me the impression that this fact was not well known. How surprising then, on rereading Keeper of the Keys for the first time in half a century, to see the connection carefully explained in the book’s ancillary material.

Biggers’ intent was to present a heroic Chinese American character as a counterweight to the all too many Chinese characters depicted as evil masterminds or just common criminals. The Yellow Peril trope was unfortunately common at the time Biggers was writing. Hence his depiction of Chan as a brilliant detective, incorrupt, a family man. Rather than being an Asiatic menace to America, he works to protect it. He is admirable in almost all ways, lacking only those virtues that might make him threatening2.

In fact, Biggers weighs the scales so heavily in favour of Chinese characters that the practice takes on an unintentionally humorous air. The Chinese people Chan meets are invariably good people. White people enthuse about Chinese people so effusively and so consistently that one wonders if the Chinese Exclusion Act was some sort of typographical error.

Despite Biggers’ laudable aspirations, Chan is has become a controversial character. Certain aspects of his portrayal have not aged well. Some critics might say “Well, fair for its time,” whereas others might dwell on Chan’s problematic aspects. There’s a peculiar statistical anomaly in that the critics defending Chan’s portrayal tend to be white whereas the critics … critiquing it tend to be Asian. This is probably just another odd pattern of the sort one should expect from small sample sets.

Chan isn’t a very nuanced character3. It’s not surprising that recent efforts to revive the character have stalled4. One might take the positive view that thanks in part to characters like Charlie Chan, racism against Chinese has weakened. Obviously, that’s complete nonsense, as racism of all varieties not only flourishes, it is the basis of successful political campaigns.

I might have wondered how much of Charlie Chan’s mannerisms were an act to calm otherwise easily alarmed white xenophobes. I didn’t, because early in the novel Chan interacts with a Chinese American couple and he’s just the same with them as he is with anyone.

One must note that Biggers wasn’t really going for depth of character. He writes in the tradition of Agatha Christie, in which cardboard characters to their best to move the mystery along. All his characters are one-dimensional and often defined by their nationality. Chinese readers at the time reportedly approved of Chan, but Italian readers were probably upset by the excitable, shiftless, greedy Romano.

This is not a mystery that keeps the reader guessing. A reliable rule of thumb for real-life murder (which I will not reveal here) identifies the likely killer early in the book. There isn’t all that much suspense.

I have many shelves of mysteries but only one Charlie Chan novel, which suggests that teen me wasn’t all that keen on Charlie Chan. Rereading this many years later, I found that I could at least enjoy it as a historic artifact.

Still, there is one part of the book that stayed with me in the half-century since I read this, Charlie Chan’s lamentation about the limbo in which he finds himself.

“I was ambitious. I sought success. For what I have won, I paid the price. Am I an American? No. Am I, then, a Chinese? Not in the eyes of Ah Sing.”

Keeper of the Keys is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Chapters-Indigo), and here (Words Worth Books). I did not find Keeper of the Keys at Apple Books.

1: Connie Willis stories to the contrary, it does snow in Hawai‘i… but nowhere near Chan’s Honolulu. He would have had to travel to the Big Island’s Mauna Loa or Mauna Kea, or to Maui’s Haleakalā and he’d need to be lucky in his timing, as the snow does not linger.

2: Chan isn’t threatening. He’s not a master of martial arts. He’s not especially good-looking and does not make women’s hearts go pitapat. This is probably for the best, as there is a Mrs. Chan and she would not approve.

3: Chan of the books, I mean. Chan of the movies is a caricature.

4: Despite being aware of Hollywood’s casting habits (Chan himself is almost always played by a white man, Keye Luke being a notable exception), I was still surprised to discover that in The Amazing Chan and the Chan Clan Jodie Foster played Charlie Chan’s daughter. Interestingly, the part originally went to Asian actor Leslie Kumamota but was then recast due to concerns that viewers would not be able to understand Kumamota’s accent.

Is Leslie Kumamota’s surname misspelled? Kumamoto is far more common than Kumamota, although I did find at least one other Kumamota. If it’s a misspelling of her surname, it’s a widespread one. That actor is credited as Kumamota on IMDB, Wikipedia, and TV Guide. It may be that they’re all quoting the same incorrect source.