Dream, When You’re Feeling Blue

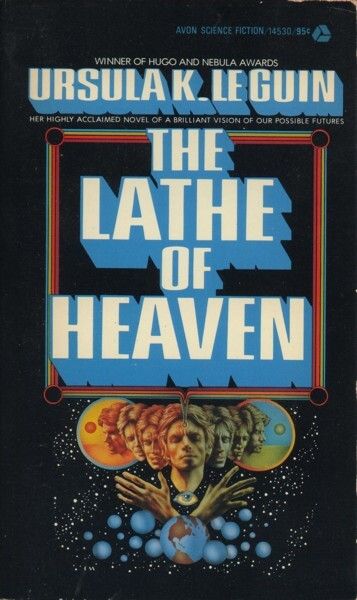

The Lathe of Heaven

By Ursula K. Le Guin

18 Apr, 2021

Ursula Le Guin’s 1971 The Lathe of Heaven is a standalone science fiction novel.

Despite the distractions of a polluted, overpopulated world forever on the brink of final war, Dr. William Haber does his best to diligently perform his duties. The task at hand: to assist seemingly unremarkable drug abuser George Orr deal with his crippling fear of dreams, Haber plans to use hypnotherapy and his own invention, the marvellous dream-inducing Augmenter.

Haber soon learns that Orr is anything but unremarkable. Orr is a living wish machine, a genie in a bottle that Haber is uniquely qualified to open.

Orr’s powers saved billions of lives in 1998. As Orr lay dying in the radiation-soaked wastelands left in the wake of total nuclear war, he dreamed his way from apocalypse to a world that, while problematic in many ways, would not immediately kill him. One might therefore question why Orr should be so terrified of his world-shaping dreams.

The problem is that while Orr can set goals, the means by which his dreams achieve them is outside of his control. A wish for sexually predatory Aunt Ethel to no longer live with his family was fulfilled when a fatal accident struck her down. Orr does not want to warp reality if it leads to more deaths.

It’s usually the case that only Orr is aware of the changes he has wrought. However, proximity to Orr seems to confer a degree of immunity to the alterations. Haber can therefore remember the world before he tested Orr’s claims and the new one that resulted. The visionary doctor sets out to do what Orr should have done: fix the world!

And should the results of each universe-altering dream fail to meet expectations? Why, simply try again and again and again until the world meets Dr. Haber’s exacting specifications.

~oOo~

This is a complete novel in 175 pages. Modern authors, take note.

Interesting trivia: Lathe was adapted into a movie that did not betray the author’s vision and was also worth watching. A curious phenomenon in a world where usually the best one can hope for Le Guin adaptations is that they won’t misspell the title or the author’s name.

Haber is a wretched behaviorist who prioritizes his own hobby horses over his patient’s happiness and well being. Which is to say, Haber is very nearly an ideal Campbellian hero, the sort of man with the clarity to see what must be done and the grit to do it regardless of cost to lesser people. To quote Haber’s speech given when Orr showed weak-minded distress at the current reality’s citizen-vigilante enforced euthanasia:

This is a tough-minded world we’ve got going here, George. A realistic one. But as I said, life can’t be safe. This society is tough-minded, and getting tougher yearly: the future will justify it. We need health. We simply have no room for the incurables, the gene-damaged who degrade the species; we have no time for wasted, useless suffering.”

This attitude would have been celebrated if Haber had been figuring in the pages of Astounding, where characters could eliminate any number of folks in the quest for racial perfection or ideal mass ratio. Tragically for the bold visionary, his author is Ursula Le Guin, who takes a somewhat dimmer view of his aspirations. She might use the word hubris for Haber’s project: transforming the world into bland grayness while racking up a body count in the billions.

While Haber’s determination to press on in the face of unintended consequences is of course worthy of approbation, there is an entity that is even more at fault, which is to say that which manifests the changes in the most malicious manner possible, like a malevolent Dungeon Master punishing a player character for wielding a ring of unlimited wishes provided by the DM themselves. On close examination, this would appear to be Ursula Le Guin herself. The author wants events to work out as they do to drive home a lesson about the perils of positivism over tranquil acceptance. OK, interesting point but one that would better if failure was driven purely by the inherent flaws in Haber’s world view, rather than by the author’s fiat.

Unsurprisingly, Le Guin’s slender, skillfully crafted novel was nominated for a Hugo. Somewhat more surprisingly, it lost to Philip José Farmer’s unremarkable To Your Scattered Bodies Go1. Strange indeed are the ways of Hugo voters.

The Lathe of Heavenis available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Book Depository), and here (Chapters-Indigo).

1: And you thought I would get through this without a footnote.

The Best Novel nominees were as follows (winner bolded):

- To Your Scattered Bodies Go by Philip José Farmer

- The Lathe of Heaven by Ursula K. Le Guin

- Dragonquest by Anne McCaffrey

- Jack of Shadows by Roger Zelazny

- A Time of Changes by Robert Silverberg

This was not the only Hugo a Le Guin work would lose to an inferior work in 1972:

Best Short Story

- “Inconstant Moon” by Larry Niven

- “Vaster Than Empires and More Slow” by Ursula K. Le Guin

- “The Autumn Land” by Clifford D. Simak

- “The Bear with the Knot on His Tail” by Stephen Tall

- “Sky” by R. A. Lafferty

- “All the Last Wars at Once” by George Alec Effinger