Earth Below Us

Shuttle Down

By G. Harry Stine

25 Apr, 2021

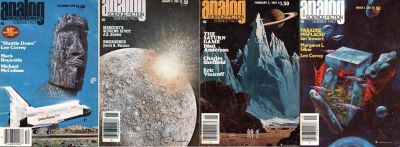

G. Harry Stine’s Shuttle Down is a standalone near-future science fiction novel, published under his Lee Correy pen name. First serialized in Analog from December 1980 to March 19811, it saw print in mass market paperback form in 19812.

Dateline: Tomorrow AD! The space shuttle Atlantis launches from Vandenberg AFB to deliver a Landsat satellite to orbit. A premature main-engine cut-off leaves the shuttle with insufficient velocity to reach orbit. The shuttle must manage to return to the Earth’s surface, using only the limited propulsion provided by its orbital maneuvering system.

Inconveniently for the shuttle and its crew — Frank King, Jacqueline Hart, Lew Clay, and George “Hap” Hazzard — Landsats live in sun-synchronous polar orbits. Rather than the abundance of potential emergency landing strips an equatorial orbit offers, most of the Earth’s surface under the shuttle’s path is ocean.

With one very small exception: Rapa Nui, also known as Isla de Pascua or Easter Island. Providentially, the island’s runway is long enough that a shuttle can make an emergency landing. Once the Atlantis is down, however, significant logistical challenges present themselves.

Ailing spacecraft fall outside the contingencies with which military governor Ernesto Obregon expected to deal. Nevertheless, the shuttle on the island’s runway is a reality with which Ernesto must deal. He soon discovers that the peculiar legal status of the shuttle (something of an aircraft, something of a space craft) means the vehicle and its crew are not carrying the standard equipment or documentation that any stranded airplane would have. The crew cannot even prove they are who they say they are. Luckily for the Americans, while Ernesto is determined to prevent any American disregard for Chilean sovereignty, he is also a reasonable man who wants to manage the crisis as best he can within the remit of his authority.

Diplomatic challenges extend beyond Ernesto’s domain. NASA has emergency landing arrangements with various nations. Chile, as it happens, is not one of them. Only broad UN treaties apply. While not actively hostile to each other, US-Chilean relations are cool. Thus, it falls to American functionaries like Joyce Fisher to smooth the way, carefully steering their US colleagues past potential culture clashes with the Chileans while determining just what it will take to get Chile to allow the US to retrieve Atlantis.

But even the best diplomacy cannot erase the significant logistical challenges NASA faces.

- Rapa Nui is isolated, farther from the nearest mainland than the range of the aircraft that usually ferries the shuttle.

- Rapa Nui has a tiny population, many of whom are backward islanders3.

- It has almost no modern infrastructure. The main radio is World-War-Two vintage and the backup is even older.

- The runway in which the shuttle is parked is the only runway; it is too narrow for most modern aircraft.

- The shuttle cannot be moved off the end of the runway because while the natives have the muscle power to shift it, the toxic OMS fuel is a danger requiring special equipment to manage that is nowhere to be found on the island.

- There is not even sufficient housing for the small army of technicians NASA proposes to land on the island.

- Local power generation is quite limited.

- Fuel is limited.

- Potable water is limited and as Hap Hazzard discovers the hard way, the local dysentery is a strain to which Americans have no resistance.

If technical, diplomatic, and social challenges were not enough, there is also the commie threat. Even as the US and Chile work towards a mutually agreeable resolution to the crisis, the Soviet Union — communists all! —schemes to exploit the mishap for their dire Red ends. Those dirty rats!

~oOo~

The commie threat subplot is rather perfunctory and entirely unnecessary. The Soviets may have engineered the whole thing to kneecap the US space program. They appear to have contemplated stealing the shuttle from Easter Island. But if this silly subplot were removed, no harm would be done to the main narrative.

The author’s depiction of the Rapa Nui inhabitants is legit horrifying. They are described as childlike thieves with no grasp of the concept of property. Their sexual mores are unacceptable to right-thinking Americans and Chileans. They are therefore confined to their village. They must have permission from the military governor to leave it (this doesn’t stop them from rustling sheep from the Chilean military).

The novel does end on what the author thinks is a hopeful note. Chile is demanding infrastructural improvements as their price for assisting the US. Surely these improvements will aid all the residents. However, some of the characters worry that the sheltered, ignorant locals will have a hard time coping with exposure to the wider world. Oh the white man’s burden!

This novel is set in a world where either the CIA-instigated coup of 11 September 1973 never occurred or General Augusto Pinochet’s junta soon fell from power. Page 58 bluntly states “Chile is a democracy.” Perhaps the best explanation is that Stine had never heard about the coup.

While the Chileans are not unreasonable, they are very determined to ensure that A) they are properly compensated for their inconvenience and B) the end result is nota permanent US military presence on Rapa Nui. Most of the knuckleheads in this book are American. Once on the island, Americans have to be reminded to get Ernesto’s permission before taking action. A particularly obnoxious American journalist objects to Chileans speaking Spanish within her hearing.

There’s also the little matter of the US apparently having never considered the possibility that there might be a shuttle mishap when it was on a polar orbit4.

Retrieving the shuttle from the middle of nowhere5 is an interesting problem. Solving it is enough of a plot to power the book. Apparently, Stine didn’t believe that, as he felt a need to close the book with an exciting climax: a sudden terrorist attack at the end of the novel.

I’ve read a number of Stine books lately. Shuttle Down would have been better with some slash-and-burn editing. Nevertheless, there’s an interesting problem at the heart of the novel, which may be Stine’s best.

Shuttle Downis out of print.

1: Which is where I first read it, the pretext upon which I justify its inclusion in Because My Tears Are Delicious to You, which as we all know only covers books I read as a teen, between March 18, 1974 and March 18, 1981.

2: The ISFDB says this happened in April 1981, but Amazon thinks the book actually came out in March 1981, so perhaps I did not need to cite the serial. Best to be sure.

3: At least according to Ernesto.

4: Even though the real-world shuttle would have been able to deliver 40,000 pounds to polar orbit, as far I can tell, it was never used to do this.

5: Antarctica would have been worse. Fewer diplomatic issues, but greater logistical challenges.