Fighting Dragons

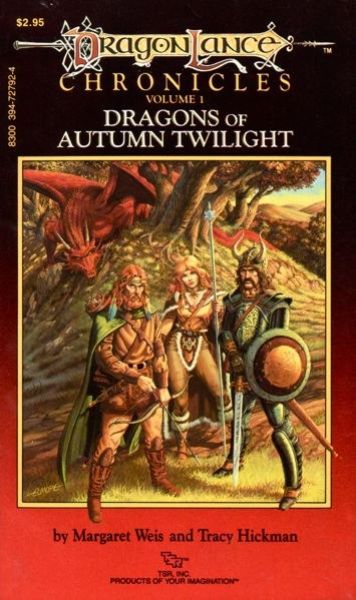

Dragons of Autumn Twilight (Dragonlance Chronicles, volume 1)

By Margaret Weis & Tracy Hickman

20 Jan, 2022

1984’s Dragons of Autumn Twilight is the first volume in Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman’s Dragonlance Chronicles. Curiously for a trilogy, the Chronicles comprise but three volumes.

Tanis Half-Elven (bastard half-elf)1, Sturm Brightblade (a would-be knight), Caramon Majere (fighter), Raistlin Majere (magic user and Caramon’s sickly brother), Flint Fireforge (dwarf grognard), and Tasslehoff Burrfoot (kleptomaniac hobbit kender) reunite in the Inn of the Last Home to regale each other with tales of the adventures each has had in the five years since they last met.

One Companion is missing. Kitiara Uth Matar, Caramon and Raistlin’s half-sister and future villain, sends a note saying that she will not attend. Flint proclaims this development bad luck. This pessimistic proclamation is too optimistic by half.

Three centuries earlier, the gods abandoned the world of Krynn. This was merely the end of organized religion devoted to actual deities. Organized religions persisted, now more focused on enriching their leaders and holding power (often used unfairly and abusively). Case in point: Solace, the village that is home to the Inn of the Last Home, has fallen under the sway of the Seekers. The local Seeker Theocrat is bent on establishing control. Hobgoblin Fewmaster Toede’s goblins keep the people of Solace in line for the Theocrat.

When barbarian princess Goldmoon arrives in Solace bearing a mysterious blue staff, the Theocrat’s first instinct is to confiscate it. He fails abjectly, as do others who try to take the staff from Goldmoon. The staff is the first divine artifact seen in Krynn in three hundred years and it is quite particular about who carries it and who wields its magic.

Of course, the Companions’ immediate reaction is to ally with Goldmoon and her barbarian guard/lover, Riverwind. Although more than a match for any given Seeker minion, the party is outnumbered. They flee Solace.

No sooner do they escape the Theocrat than the party encounters cloaked Draconians, a race unfamiliar to them and a harbinger of events to transpire. Eluding the lizardmen takes the party into the cursed Darken Wood. They are then rescued from the undead who call the wood home by a unicorn calling itself the Forestmaster.

While the Forestmaster is no doubt altruistic in a general sense, in this case rescue has a price. The party must find its way to the ruined city of ruined city of Xak Tsaroth. If the Companions are lucky, hardworking, and observant, they will find and retrieve the Disks of Mishakal and thus re-establish the teaching of the True Gods. Perhaps they will return the True Faith to Krynn!

Or perhaps they will die discovering that dragons have returned to their world. Either way, their adventures are only beginning.

~oOo~

To rip the Band-Aid off immediately, while this novel is significant in the history of the fantasy genre, it is a wretched fantasy novel. I found it barely readable.

Like Quag Keep, Dragons of Autumn Twilight is overtly a Dungeons & Dragons (Specifically, an Advanced Dungeons & Dragons) tie-in novel. Unlike Quag Keep, the novel was published by AD&D publisher TSR. Unlike Norton, the authors were quite familiar with AD&D as it existed in the early 1980s.

Dragons of Autumn Twilight’s genesis came from Weis and Hickman’s involvement in what was originally called Project Overlord. Whereas many pre-generated adventures had limited scope, Project Overlord—or Dragonlance, as it became known to the public—was an epic twelve-module set of AD&D adventures, each adventure focusing on a different variety of colour-coded dragon. This bold gambit proved popular.

Writing a tie-in novel for the series may seem to us like a no-brainer but in fact that was not, as far as I can tell, common practice at the time2. Weis and Hickman were not the first picks to write the novel. An unnamed author was. Deeming that person’s work unsatisfactory, the task of writing the novel fell to TSR employees Weis and Hickman. Thus the book in hand.

It’s just too bad Dragons of Autumn Twilight is comprehensively derivative and badly written, on par with Quag Keep (or perhaps worse, since Quag Keep was at least shorter). Indeed, the authors’ familiarity with AD&D may have worked against them, as one can see game mechanic gears whirring3, and work out the class to which each character belongs4. This may be due to the fact that the game material preceded the first novel. The book reads less like a proper novel and more like a player’s journal of a campaign run by a DM unafraid to give his characters a firm nudge in the direction the plot requires.

As anyone familiar with (unrelated) The Sword of Shannara’s success years earlier could have predicted, being a nigh-unreadable wodge of clunky prose and creaky plotting (ornamented with Tolkienesque details whose serial numbers were lovingly filed off) mattered much less than scratching the right itch at the right time5. In 1984, enough readers wanted a straightforward secondary-world fantasy adventure that the book was a best seller. Writing from the perspective of a former RPG store owner, the novel was wildly successful, by far the best-selling fantasy novel in stock in 1984. If one looks at the number of fiction titles published per year by TSR, one can definitely see an uptick following Dragons of Autumn Twilight’s publication. To this day, I know people to whom this novel and the series of which it is a part are a treasured part of their teen years. The authors certainly went on to have long, prolific careers.

Dragons Of Autumn Twilight is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Book Depository), and here (Chapters-Indigo). Unlike Quag Keep, I do not believe it has ever been out of print.

1: Persons familiar with common early RPG tropes may be curious how long it takes before the first reference to rape appears. That turns out to be roughly as long as it takes the first mixed-race character to appear.

2: Wikipedia claims that TSR was reluctant to publish the novel. This does not appear to be the case. Perhaps a Wikipedia editor was confused by the accurate tale that the first writer hired was dismissed; thinking that this meant that TSR didn’t want to publish the novel.

3: Certain races (like goblins) are irredeemably evil in the novel, others (like the Gully dwarves) are hopelessly inferior, and all of them (save possibly humans) have certain intrinsic behaviors (like kender kleptomania) baked in. This comes directly from AD&D game mechanics, which in turn are rooted in D&D designer Gary Gygax’s worldview (Gygax having once defended Colonel John “Nits make Lice” Chivington as Lawful Good). Among the consequences: race-based prejudices are perfectly functional in AD&D. Killing goblins on sight is simple self-defense, while jailing any kender in sight is merely crime prevention. Later editions of the game are moving away from this design philosophy.

4: To be fair, not entirely a bad thing. Sickly Raistlin’s origin is rooted in the person playing him rolling a natural three on 3d6 for his constitution—the lowest value possible—and deciding to run with it.

5: I would make fun of these readers were I not familiar with the less than stellar quality of the SF novels I hoovered up as a teen.