Footfall

Footfall

By Larry Niven & Jerry Pournelle

3 Aug, 2014

0 comments

I remembered Footfall as one of those excessively long science fiction novels of the pre-Aught Three and when I picked it up I was surprised to see that my May 1986 Del Rey mass market paperback was only 582 pages (including the authors’ bios at the end), barely an evening’s read. When I put the book back down eight long hours later, I was still surprised that Footfall was only 582 pages because the authors managed cram in the mediocrity and tedium of a much longer novel.

It’s still better than a lot of the competition.

But first! Some context:

In the long long ago of the early Disco Era, Niven had a sense of joy, Pournelle was a Campbell-Award winning author and together they wrote The Mote in God’s Eye, a long novel about managing a fraught First Contact with as low a megadeath count as possible. Having enjoyed success once, Niven and Pournelle continued the partnership, rewriting Dante’s Inferno, smashing the planet with a comet, creating a portrait of the world’s largest gated community and so on. Over the years, to borrow from Alan Moore, Niven grew more like Pournelle; Pournelle too became more like Pournelle.

Their late ’70s disaster novel Lucifer’s Hammer started off as an alien invasion story that featured a deliberate asteroid impact; their editor apparently liked the asteroid but was cool on the aliens. What emerged was a conventional disaster novel written in the matter of the 1970s best seller novel, thick and with a cast of thousands. The original idea was still bouncing out in their heads and almost a decade later the pair finally got back to it in this novel.

In a 1995 as imagined by a ex-Red turned right-wing ideologue, America has surrendered supremacy in space to the Soviets, whose command of space out to the Moon is unquestioned. We are denied the chance to see if internal rot eats the US from the inside out before or after the imperial might of the glorious and eternal Soviet Union crushes poor, doomed America because before things can come to a boil an external event renders most terrestrial politics moot: aliens have been hiding out by Saturn for the better part of a generation and now they are ready to act.

The alien’s arrival in the Solar System went overlooked because nobody happened to be looking in the right direction at the right time but there’s no such thing as stealth in space and in 1995 enough people are looking at Saturn when the alien mother-ship sets out for Earth that humanity has months of warning to prepare their responses. It is obvious any civilization able to travel between stars commands a vastly superior technological kit than any nation on Earth and that open war should be avoided if possible. It’s not clear if violent conflict can be avoided and so the various human factions make their plans, hoping for peace, preparing for war.

The elephant-like aliens for both historical and cultural reasons see no alternative but to crush humanity, although they don’t intend or want to wipe us out; thanks to their unfamiliarity with human psychology, their attempt to get it over with a glorious moment of shock and awe is doomed to fail abjectly. Their occupation of Kansas reveals to the aliens how poorly they understand humans; the means by which the occupying forces are removed from the face of Kansas gives them a hint as to how far the humans are willing to go to resist being conquered.

What follows is a brutal, escalating struggle between two sides with rapidly dwindling resources; the aliens have superior technology but a small population, while the humans have the advantage of numbers but have difficulty bringing that advantage to bear. No clear path to compromise exists and eventually the plot narrows down to one glorious confrontation between invaders and defenders whose outcome will determine the future of the Earth and its Solar System.

So, the bad first:

One flaw is built in by nature of the sub-genre: realistically the scale of the universe suggests first contact between humans and aliens would be less like Cook in Hawaii and more like Lord Shiva squaring off against a toddler. For the conflict to be interesting, the aliens have to handicapped somehow, whether it’s limiting their available resources, egregious ignorance about Earth or making them hyper-conservative dullards whose technological advantage over the Earth is entirely due to their possession of Coles Notes to Superscience. I will concede there probably isn’t a thrilling war story without the author nobbling the aliens somehow.

[It’s possible but not hinted at that the coincidence in time of the aliens and the humans is due to the Precursors]

In general, if energetic right-wingery offends you, avoid SF in general and Niven and Pournelle in particular. That said, while I remembered the journalist being drowned in the toilet, I had completely forgotten the business where the Right People step in at the last moment to protect humanity from the ravages of elected government.

Let us walk by the gender politics, eye averted. Likewise, nobody needs to relive the bits about the porn tape or the parts about the struggle to have freedom without filthy dirty license.

I regret that I did not reread this long enough ago to ask Fred Pohl how he felt about how the book divides the SF writers into military veterans or liberals. I would also have liked to ask Theodore Cogswell what he thought.

I also understand that hard SF, which is to say SF written by one small cabal of writers centered in Southern California, has its particular set of obligatory tropes and conventions, but I was still surprised at how early the required dig at Proxmire turned up (Page 33, if you care).

The doleful prediction of a Red Solar System was amusing in retrospect; the Russians certainly could be seen as having a more robust crewed space program than the US (although the US kicked the SU as far as uncrewed probes go) but in the end crewed space flight was completely irrelevant to the resolution of the Cold War.

The advantage of the cast of thousands approach is that it allows authors to pad the page count easily. The disadvantage is it limits the room for character development (which I guess is really only a disadvantage if the author actually does character development). I found it hard to care about most of the characters because most were sketches. I certainly wouldn’t be able to name most of them without notes. The added length resulted in serious plot fatigue for me; I was ready to stop reading by page 400.

I think it would have been nice if the Nigerian astronaut had been better defined than “that very dark skinned guy who spends most of his time being terrified until he dies of fright part way through the book.” I was never able to determine if he had a name, which I think is a bit sad. The other significant black guy, Carter, is treated more reasonably and while it’s true his last appearance makes it unlikely he will be appearing in any sequels, he has a lot of company in that.

Dear god, let me never again encounter a Niven/Pournelle sex scene. I have a feeling they were Niven’s fault; I remember some very sexy bits from Neutron Star whereas nothing similar is coming to mind from Pournelle. Ann Aguirre has argued that there should be more room for sex in SF but while I agree sex is a wonderful part of human existence, I don’t think Aguirre understands the horrors that could be unleashed if authors like Niven and Pournelle followed her advice. The living would envy the dead.

The pair are foolishly specific about the asteroid impact in the Indian Ocean from which the novel takes its title. The impact is 4,000 megatons, which is admittedly bad but well short of the 130,000,000 megatons of Chicxulub – huh, apparently I’ve used Chicxulub before – and only about five times larger than the 1812 eruption of Tambora. N&P have Footfall triggering earthquakes around the planet; I strongly doubt that would be the case.

Like most science fiction readers, I keep my copy of Hazards Due to Comets and Asteroids one execuglide away. As we all know, Hazards says that wave height for an impact in deep water is roughly

h = 6.5m [y/gigaton] 0.54 [1000km/r]

h = wave height

r = range to impact

y = yield

Tsunamis have the annoying property that wave height drops off linearly with distance, which is why a quake in Chile can kill people in Hawaii.

Idealised wave run in (which is to say, not applicable to any real region):

Xmax ≈ 1.0km [h/10 meters] 4/3

At a thousand kilometers, the wave is 14m tall and the idealized run in would be a couple of kilometers. People tend to live near coasts and places like Bangladesh present less an idealized example and more the worse possible case of millions of people living meters above peak tides but it seems to me clear that while prompt deaths due to Footfall would be millions or tens of millions, they would be nowhere close to justifying lines like “[Stalin] would have been pleased to have a simple answer to the India ‘problem’. [p 388] India had half a billion people before Footfall; it will probably have about a half a billion people after.

These may be the actual distances from the stated impact site of some interesting locations (usual ‘cribbed without double checking in full knowledge that I will be a figure of justified mockery if these are wrong’ warning):

- Mombasa: 3342km

- Perth: 5163km

- Chennai 4324km

- Mumbai: 4703km

- Diego Garcia:1903 km

(Now, you’d right to point out Hazards post-dates Footfall but it cribs heavily from Glasstone and everyone has a copy of Glasstone)

I for one have a very low tolerance of hand-jobs from science fiction writers, coy in-jokes and thinly veiled cameos from SF authors and their friends. This book devotes a significant number of pages to characters based on Niven, Pournelle, Cherryh, Heinlein and others, assembled as an advisory team for the government (Sadly, SIGMA has shown that if you try this you end up with one author promoting a spitefully bigoted medical fraud while another has his own personal Alexander Haig moment; the utility to America is not obvious). It’s true Fallen Angel’s handies were even more off-putting but that doesn’t mean that Footfall’s were any good.

But the book isn’t entirely terrible, at least if you consider it in comparison to other books in the same subgenre. It’s true I wanted Footfall to be over by page 400 but if this had been by Harry Turtledove, it would have been at least six turgid volumes long. Possibly twelve.

I suspect Niven designed the aliens. As usual he paints with a very broad brush but at least if I say “elephant-like aliens” people have a good chance of guessing “Fithp” whereas if I say “genocidal space lizards”, people may have no idea if I mean the Aan, the Xan-Sskarns, the Visitors or some other equally generic aliens.

(because we’re dealing with a single community of aliens, one can also assure oneself that this is just a particularly bone-headed group. Even as small as it is, we do see variation, disagreement and divisions within the group)

Footfall’s energy is too low for the effects it has but at least the authors did not depopulate the Golden Triangle with a meteor the volume of a bungalow, unlike Bear in Scardown.

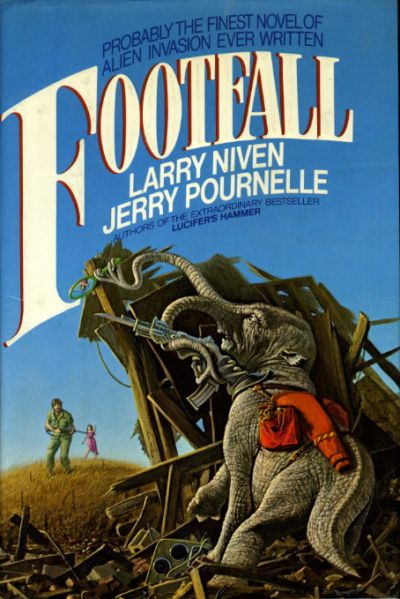

I am not a big fan of Michael Whelan – it’s a texture thing — but consider the alternative:

I am not a big fan of Michael Whelan – it’s a texture thing — but consider the alternative:

or more fairly, this uninspired Footfall cover:

or more fairly, this uninspired Footfall cover:

Whelan’s covers are relevant to the books his art graces and he puts in an effort to create an interesting and eye-catching piece. There is a reason he wins Hugos and why so many best-selling F&SF novels of the period had a Whelan cover. This is the full art he created:

There is the small puzzle of what happens to Anson, the Heinlein expy. He becomes past tense at some point and the how was never explained. I like to think he allowed the other writers to kill and eat him so they could absorb his qualities, in the secret belief that he would assimilate all of them from the inside.

I wasn’t keen on Footfall and I probably will never read it except for research purposes but it certainly could have been much worse; at least it didn’t have any plucky and sympathetic transsexuals tortured, eaten and killed — in that order — by cannibalistic Koreans. “It could have been much worse” might seem like a low bar but it’s a level of expectation for science fiction many science fiction novels fail to clear and one I will settle for.