Garden of the Mind

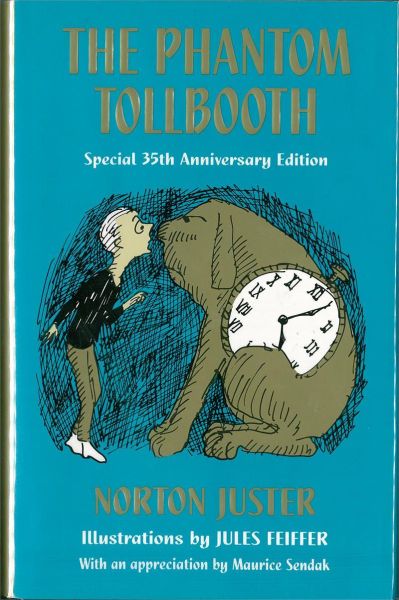

The Phantom Tollbooth

By Norton Juster

6 Mar, 2017

0 comments

Norton Juster’s 1961 The Phantom Tollbooth is a widely loved whimsical children’s book that, as it happens, I’ve not read until now.

There was once a boy named Milo who didn’t know what to do with himself — not just sometimes, but always. When he was in school he longed to be out, and when he was out he longed to be in. On the way he thought about coming home, and coming home he thought about going. Wherever he was he wished he were somewhere else, and when he got there he wondered why he’d bothered. Nothing really interested him — least of all the things that should have.

When Milo comes home to find a mysterious package awaiting him, he sees no point to assembling the contents … but he does so anyway. Not assembling them would have been just as pointless and at least putting the strange present together was something to do.

His gift is a tollbooth. A very special tollbooth.

On a whim, Milo pays his toll and drives his replica electric car past the tollbooth. He is astounded to find himself far from home. Astounded but oddly enough, not alarmed. Milo begins to experience a feeling previously alien to him: happiness.

Milo is in a land of words and numbers, a place where figures of speech have physical reality. Or rather, he is in a land of words or numbers, thanks to some very bad decisions by proud but foolish rulers. Rather than accept the compromise offered by the Princesses Rhyme and Reason, King Azaz of Dictionopolis and the Mathemagician of Digitopolis have banished the Princesses. Words and numbers existing in separate domains, in isolation from each other, is clearly foolish, but without the Princesses Rhyme and Reason, there is no wisdom.

Someone needs to retrieve the Princesses from the Castle in the Air. Milo is a someone. Moreover, he and his companions — the Humbug and Tock the Watch Dog — are someones who lack the experience to know when they have been voluntold for a quest. Someones whom the King and the Mathemagician would be willing to send off into a land filled with monsters and demons of all kinds.

Milo may be trepidatious, nervous, and unsure. But he is not bored. His life is worth living! But it may prove very short.

~oOo~

The particular edition I have in hand is the 35 th anniversary edition, which is inexplicably somehow twenty-one years old, even though the novel itself is only as old as I am. It is a mystery. The 35 th edition includes an introduction by Maurice Sendak, who is almost inarticulate with enthusiasm for The Phantom Tollbooth.

I am mainly familiar with Jules Fieffer’s work from the Village Voice (there’s one particular political cartoonist who seems especially apt these days). I would not have thought of him as a children’s cartoonist, but his style is eminently suitable for the unsure Milo.

That remarkable opening passage made me wonder if part of Milo’s problem is clinical depression. I wonder the same thing about Charlie Brown 1. Perhaps the problems the protagonists face seem so insurmountable because the protagonists are being betrayed by their brain chemistry. 1961’s unsophisticated pharmacopoeia may have consigned Milo to anhedonia, but it gave us a children’s classic.

The Phantom Tollbooth brings to mind John Myers Myers 1949 fantasy Silverlock.The two books have many common features, from the protagonists’ inability to enjoy life to the worlds of letters in which they find themselves. Still, the differences outweigh the similarities. The Phantom Tollbooth seems to me a more good-natured work than the Myers. Myers filled his book with references to works of fiction, Juster with an amazing density of wordplay.

It’s not surprising that Milo’s essential good nature turns out to be an asset. In children’s stories, the people one helps often repay the favour. If you think you might be a character in a children’s book, always help strangers! Of course, in real life, this strategy may not always pay off, but at least you’ll have the pleasure of having done the right thing.

What’s less usual for a kid’s story is that Milo manages to out-think many of his obstacles. Of course, that makes perfect sense in a book like this, which assures us that learning and thinking are fun, but it is a pleasant change from protagonists who prevail because they’re stubborn and because they are The Chosen One.

I would have loved this as a kid. A lot of luckier children appear to have enjoyed it 2. I enjoyed it greatly as an adult.

The Phantom Tollbooth is available here (Amazon) and here (Chapters-Indigo).

Please direct corrections to jdnicoll at panix dot com

1: Actually, I don’t doubt that Charlie Brown is depressed.

And his friends and family don’t help.

2: Eventually. It seems that this novel was not an immediate hit. In fact, I suspect had things gone just a little differently, it could have vanished without a trace. One wonders how many equally good but less lucky books there were.