Hush Don’t Cry

Childhood’s End

By Arthur C. Clarke

3 Nov, 2024

Arthur C. Clarke’s 1953 Childhood’s End1 is a near-future novel about human destiny.

1985: the world is on the brink of determining whether democracy’s Nazi rocket scientists are better than Communism’s Nazi rocket scientists… when the question suddenly becomes moot. Vast alien starships appear over humanity’s cities. The Earth and all on it are now under the rule of the Overlords.

What horrific purpose have the aliens in mind for their human subjects? And why will they not reveal their true form to humans?

The tale is told in three sections.

Earth and the Overlords

The Overlords have relentlessly forced on humanity measures designed to improve the day-to-day quality of life for humans and animals. Ethnic minorities may not be persecuted, animal cruelty is banned, and nation-states are amalgamated into sensible administrative domains.

Naturally, plucky humans resist being ruled for their own good.

The Overlords themselves are out of reach. The brave freedom fighters of the Freedom League settle for kidnapping UN Secretary General Stormgren, hoping to bring pressure on Karellen, the Overlord Supervisor for Earth. The hidden Overlords will be forced to accede to Freedom League demands!

This ingenious scheme is, of course, doomed to fail.

The plan does move Stormgren to wonder just what the Overlords look like. Unlike the Freedom League , Stormgren has both means and opportunity to make a try at finding out.

The Golden Age

The Overlords gave humans peace, prosperity, and integration. The whole planet is one peaceful middle-class world in which every person is free to marry whom they like2, live where they like, and pursue any occupation they like… within certain limits.

Now freely intermingling with humans, the Overlords sometimes take interest in human works. Inexplicably, this includes Rupert Blake’s extensive library on psychic phenomena. The evidence collected there leads to the conclusion that there is no such thing as psychic powers. The psychic party game that correctly identifies NGS 549672 as the heretofore secret Overlord home system is probably just a coincidence… although the Overlords aren’t treating it as a coincidence.

Among the occupations closed to humans: starfaring. Jan Rodricks believes he has found a way to circumvent the ban. Failure would be ignominious. Success (and the fact that even the Overlords cannot sidestep Einstein) would maroon Jan decades in the future.

The Last Generation

Chafing at a stagnant world, a brave community of visionaries establish a colony on a volcanic island. There, they hope to rekindle human culture. In fact, the settlers, or more exactly their children, will certainly catalyze an astonishing development, but one far other than the purpose their parents have in mind.

Only a few months older, stowaway Jan returns to an Earth eighty years older than the one he left, to discover what exactly motivated the Overlords to intervene on our world.

~oOo~

Apparently, there is a newer edition of this novel that changes the prologue to take into account the end of the Cold War. My edition has the original text.

This is another book hitherto unreviewed because I was under the impression I had already reviewed it3.

While the world of tomorrow seems to be comfortably British and middle-class, also completely race blind in a way that requires meticulously documenting every person’s skin color to show how open-minded everyone is, Clarke is not blind to the troubles that prosperity coupled with no particular need to work could bring. The people of tomorrow waste a lot of time enjoying vapid entertainment.

Do you realize that every day something like five hundred hours of radio and TV pour out over the various channels? If you went without sleep and did nothing else, you could follow less than a twentieth of the entertainment that’s available at the turn of a switch! No wonder that people are becoming passive sponges — absorbing but never creating. Did you know that the average viewing time per person is now three hours a day?

Clarke belongs to an unusual subset of science fiction authors concerned about the implications of telecommunications. This is not the last doleful scenario he spun out — “I Remember Babylon” featured Chinese communists attacking the US with satellite-broadcast pornography—but I am not sure why he thought people staring at screens all day was plausible. Who is washing the dishes in this scenario? And what about the heat from billions of cathode ray tubes?

Although classic SF generally didn’t go in for unreliable narrators, I couldn’t help but wonder if we were really supposed to believe in species orthogenesis (there’s a set sequence of evolutionary steps through which species pass) and the kindliness of the Overlords in shepherding humans towards the Next Step. One could read this book as cosmic horror, in which humans are devoured by a mysterious alien entity, aided by their Overlord minions.

Cosmic destiny aside, what caught my attention as a teen was this passage.

“Now as you may have heard, strange things happen as one approaches the speed of light. Time itself begins to flow at a different rate-to pass more slowly, so that what would be months on Earth would be no more than days on the ships of the Overlords. The effect is quite fundamental: it was discovered by the great Einstein more than a hundred years ago.

“I have made calculations based on what we know about the Stardrive, and using the firmly-established results of Relativity theory. From the viewpoint of the passengers on one of the Overlord ships, the journey to NGS 549672 will last not more than two months — even though by Earth’s reckoning forty years will have passed.”

This detail blew my mind and inspired years of fiddling around with equations for time dilation and related matters. It is too bad that relativistic star flight would seem to be impossible, even more impossible than a world with four or five television channels! Still, fiddling with those equations gave meaning and fun to my life.

At this point in the review my editor often asks me to opine on the quality of the prose and characters. Well, the prose is functional. The characters… you did see the author’s byline, right? Clarke novels are generally populated by sensible middle-class British people (even the characters who are not British) who would agree with Clarke on most subjects, and who do not much bother with being distinguishable from one another. They suffice to get the plot from A to B.

Childhood’s End is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Apple Books), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Chapters-Indigo), and here (Words Worth Books).

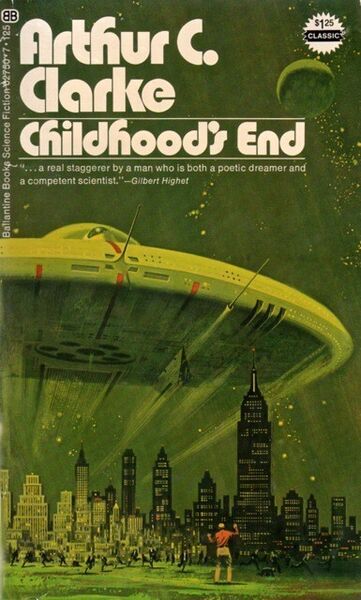

1: This is one of the rare cases where I can narrow almost exactly when I first read this. My paperback is $1.25, which means it is the November 1973 edition. The price was jacked up to an exorbitant $1.50 in January of 1974. That leaves a very narrow window in which I could have encountered this specific edition. The price rise is a tribute to the horrors of 1970s stagflation.

Canny readers will be aware that November 1973 to January 1974 is slightly earlier than the range covered by my Tears Reviews. But I know for a fact that I reread this book in the 1970s. I did like it.

2: Marriage is always with a person of the opposite gender. There are probably SF books of this vintage that feature same-sex marriages, but this is not one of them.

3: Odd coincidence. Last week, I mentioned on Bluesky a Clarke story in which all of the world’s religions disappear in a puff of logic after a time-viewer allows adherents to discover that their respective religions’ histories were false or at least grossly misunderstood. Only one religion survives. Only Buddhism is sufficiently pure and philosophical to survive the shock. I couldn’t remember the title. It was Childhood’s End.