Ice Cold Hands Takin’ Hold Of Me

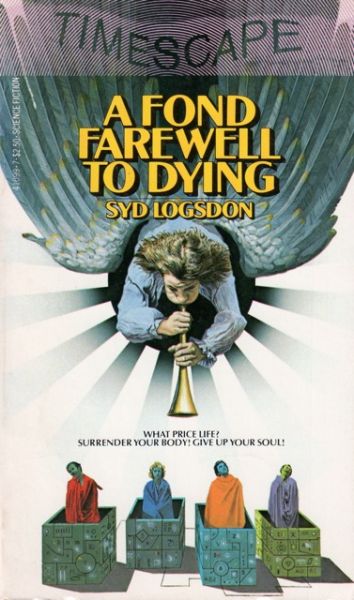

A Fond Farewell to Dying

By Syd Logsdon

29 Oct, 2017

1981’s A Fond Farewell to Dying is a novel-length expansion of Syd Logsdon’s 1978 novella To Go Not Gently.

Of all the nations of Earth, India has been least affected by the Cataclysm that ended Euro-American domination of the world. Though even India was changed: sea level rise has cut it off from mainland Asia and the fallout that made it over the Himalayas has forced birth rates below replacement levels. Two centuries after the nuclear conflict, India is a much emptier place.

Scientist David Singer has abandoned the North America of his birth for India, the most advanced nation on the planet. Now calling himself Ram David Singh, he is researching what he conceives as immortality tech. The odds of an American hick garnering the required resources from the Indian state may seen poor, but geopolitics is his friend.

India has invested billions in the Panch-ab project, constructing dikes and draining lands once known as Pakistan, lands flooded by post-war sea level rise. India’s neighbor Medina has allowed settlers into the recovered lands. This is easily played by religious extremists on both sides as a continuation of older struggles between Hindus and Muslims.

Prime Minister Sri Jogendranath Kantikarji—Sri Karji to his supporters—owes his long tenure to his skill at juggling opposing goals. He wants to avoid war between India and Medina, but also needs placate Indian nationalists. He orders an airstrike on the Mahmet, a Medinan settlement within the disputed territory. He did this knowing that his grandson Nirghaz Husain was in Mahmet. Husain loses both legs.

Sri Karji will fund Singh’s research if Singh can reliably promise to restore Husain’s legs. The most straightforward solution would be to grow a clone of Husain and transplant new legs onto the Prime Minister’s grandson. But this is impossible; the damage to the rest of Husain’s body is too great: Singh proposes a more audacious strategy: grow a Husain clone and transfer Husain’s memories into the young, healthy body. This will be a trial run for Singh’s grand plan for immortality: clones.

Singh sees no moral problems here. Husain is less sure that this strategy is permissible. Won’t this involve killing whatever personality the clone has developed, as well as euthanizing the old body? Singh’s fellow researcher Shashi Mathur has another objection: the clone may think that it is a continuation of its original, but the soul, the atman, will have migrated elsewhere. The strategy is even more obviously murder.

In the course of events, Singh, Husain, and Mathur will find out who (if anyone) is correct.

~oOo~

Rather remarkably, the justification Singh uses to pursue cloning research—addressing India’s fertility issues—turns out to be correct. The immortality game is thus far a side issue but trying to prevent further population decline has traction. The fact the elites select members of their own ethnicities to clone while excluding those lower in the pecking order as genetically unfit is unsurprising; the manner in which the book notes the injustice is a bit of a surprise.

James’ usual nitpicking re setting: it would take over 200 meters of sea level rise to cut India off from the mainland. Current estimates of the ice released by melting glaciers and ice caps predict a smaller rise (one that would still be catastrophic, of course). Logsdon does some hand-waving here, claiming that nuclear Cataclysm triggered geological tumult on the American West Coast, which then caused accelerated and amplified sea level rise. The implications for Eurasia are rather dramatic.

I was a bit hesitant to revisit this book. I was afraid that the suck fairy would visit hard, given the cultural context. The first version of this story was published in Galaxy, a year or so before this exchange over in Analog:

ASF&SF 99(4) April 1979, Brass Tacks, p. 176

Dear Ben,

Just finished "I Put My Blue Genes On" by Orson Scott Card. Good story. But it reminded me that all your stories have one major fault. They are racist by implication and by supposition. They ignore the possibility that Japanese, Chinese, Indians, Arabs, Ethiopians etc. might found civilizations in the stars. Card at least mentioned the Chinese (only to explain briefly that they had all been wiped out) to concentrate on the real world beaters of 2810 A.D. — the Americans (granted they came from Hawaii), the Russians, and the Brazilians. Western civilization all. Most of your stories just ignore the existence of Earth's other races. Even a story about a planet peopled with the descendants of Japanese space explorers (Donald Kingsbury's excellent "Shipwright") feels it necessary to explain that this is an out-of-the-way, backward planet and that real interstellar civilization is white. Hope that in the future your writers will come to accept the fact that Nigerians as well as WASPs are star bound.

Gordon Heseltine

Canandaigua, NY 14424

[The editor replies:]

Why is there no science fiction written by Eastern authors? (Assuming Russia and Japan are Western nations.) Because Eastern cultures are a-scientific. They will get to the stars aboard Western ships -—no matter who builds them.

Logsdon’s story shows that at least one SFF author had already attempted an Eastern SF story. His India isn’t the most advanced nation on Earth simply because all the others have vanished or are still recovering from barbarism1 (although that helps). This India is able to do things no pre-Cataclysm nation could match, from launching fusion-propelled orbital battle stations to developing mind-transfer techniques. The same is true to a lesser extent of neighbouring Medina; as the Indians discover, it’s amazing how powerful a beam weapon one can build if you can hook it up to a national electrical grid.

It’s also an overtly democratic India, which is unusual for any futuristic nation in disco era SF. Many of Sri Karji’s decisions are driven by his desire to avoid losing a confidence motion in parliament. How odd to see a future that isn’t autocratic2.

Logsdon also subverted another trope. One might predict that the smart white dude’s extremely devout Indian co-worker’s religious objections to his research would falter before her adoration of her ever-so-much-smarter-than-her boyfriend. That’s not what happens. Singh never changes Mathur’s mind. She’d rather kick her lover to the curb than abandon her morals. Furthermore, the author makes it clear that her critique may be well-founded. There is more going on that can be explained by Singh’s model.

I do wonder what someone who is actually familiar with India would make of this novel. Comments?

A Fond Farewell to Dying is out of print3. Used copies may be available.

1: Though North America, which at first appears to be populated by backward religious fanatic farmers, turns out to have some respectable urban centres.

2: It is, however, oligarchic.

3: It’s a sad review where I don’t learn something while researching the book in hand. In this case, I discovered that Logsdon has a new book out, 2017’s Cyan.

If ISFDB can be believed, it is his first new SF novel in 36 years....