In the Middle of Fifth Avenue

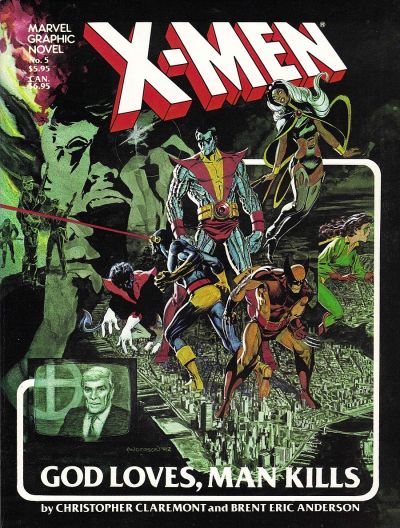

X‑Men: God Loves, Man Kills

By Chris Claremont & Brent Eric Anderson

29 Mar, 2022

1982’s X‑Men: God Loves, Man Kills is a graphic novel (sort of an American tankōbon) by Chris Claremont, with illustrations by Brent Eric Anderson. God Loves, Man Kills was in its day considered something of a classic.

Two African-American children flee — but not quickly enough. Their pursuers corner and murder both of them. The pursuers leave the bodies on display and add signs explaining their motivation for the lynching: both were mutants.

The Children of the Atom are individuals born with extraordinary superpowers. While mutants precede the atom bomb, numbers soared after Trinity. Some mutations, like the ability to synthesize vitamin C1, may be subtle but others, like generating force-bolts, controlling weather, and the ability to psychically contact every human on the planet at once, are not. The moniker “homo superior” for mutants has thus far failed to allay baseline human anxieties.

The Reverent Stryker is an extreme example of anti-mutant sentiment. Forced to deliver his wife’s baby after an auto accident marooned the Strykers in the wilderness, he was horrified to discover his child was a mutant. Secretly murdering wife and baby on the spot, he pledged to cleanse the Earth of mutants. He has spent years building the power base needed to do this. Now he is almost ready; he has only to secure one last element in his plan.

One of his opponents is Professor “Professor X” Charles Xavier. The Professor actively recruits young mutants to fight menaces in the name of human/mutant friendship. He uses his status as a known mutant to campaign for human/mutant peaceful coexistence. He agrees to a public debate with Stryker, only to discover too late that the affair is rigged to favour Stryker.

That’s just one part of a more extensive plan, which Stryker and company have hidden behind artificial psi-blockers2.

On their way back to Professor X’s Westchester mansion, Professor X and his loyal supporters, Scott “Cyclops” Summers, and Ororo “Storm” Munroe are ambushed on Central Park Drive by Stryker’s Purifiers. The police arrive to find only three corpses. Since the car was blown up by two missiles, the remains are unidentifiable. The police can do nothing but inform the Professor’s grieving students that X, Storm, and Cyclops died in a traffic accident3.

However! X‑Man Wolverine’s suite of powers includes heightened senses. He can tell the bodies are unlucky strangers4. Perhaps Charles, Scott, and Ororo were simply taken prisoner and three bodies left in their place to forestall investigation.

In fact, this is exactly what has happened. The Professor’s prodigious powers are necessary to Stryker’s scheme to kill every mutant on the planet at once. However, he must first brainwash Professor X. This gives the X‑Men time to confound the scheme … provided that they are willing to accept help from their long-time antagonist, leader of the mutant supremist terrorist group Brotherhood of Evil Mutants5 Magneto!

[break]

No doubt esteemed mutant expert Professor Andrew Deman has written about this graphic novel more incisively than I can. So I’ve been very careful not to check his writings on this subject. An ill-favored thing, sir, but mine own.

Credit where credit is due: writer Chris Claremont made the Uncanny X‑Men what they are today. Before Claremont came on board in 1975, the title did not sell well. In fact, it was cancelled in 1970. The success of Len Wein and David Cockrum’s 1975 Giant-Size X‑Men suggested there was a market for the X‑Men, if only someone could find an angle. Between 1975 (when he was assigned the title) and 1991 (when he left), Claremont transformed an underperforming title into an unstoppable juggernaut.

This particular graphic novel showcases Claremont’s creative prowess. The cast is huge and diverse. Women play central roles. Characters aren’t stoic do-gooders; they express their emotions … at length. Dialogue is so voluminous that one marvels that Claremont and the art team crammed it all in. There are lots of thrilling action scenes. Superpowers are limited in plot-facilitating ways. The one significant Claremontism missing, because this was a graphic novel and had to be complete, is Claremont’s love of dangling plot-threads.

This particular work of Claremont’s was highly regarded enough to be the basis of the second X‑Men film, X2. However, one notes there are some significant differences between graphic novel and movie. This may be because certain elements of the graphic novel aged poorly6.

For example: God Loves, Man Kills is many things but subtle ain’t one of them. Dialogue leans overwrought and melodramatic. There’s a surprising amount of torture, committed by both the villains and the ostensible good guys (granted, specifically by Wolverine, who is gray at best, and Magneto, who is a would-be genocidal terrorist, albeit a very polite and well-spoken one). It’s hard to believe that two missiles would be waved off as a traffic accident. Claremont’s use of various Black characters to draw parallels between anti-Black bigotry and the far more pressing issue of anti-mutant bigotry is unfortunate. I’d have been happier without Kitty’s use of the N‑word. The plot turns out to depend on a New York cop having a moment of moral clarity when he sees costumed Sprite as a girl about to murdered8; I know this is a fantasy but really?

Interestingly, Claremont firmly rejects a stock plot element that remained popular for decades after God Loves, Man Kills: the scene where the Bad Guy Reveals Their True Nature on television, whereupon the public immediately turns on the Bad Guy and his cause. Stryker is exposed, confounded, and arrested, but his followers do not abandon anti-mutantism.

On the one hand, this is a franchise and anti-mutant activists are too rich a source of plot to abandon. On the other hand, how many black hats in fiction were easily sidelined at the last moment simply because of a public slip of the tongue or instinctive use of a small child as a human shield?

God Loves, Man Kills is an important part of the history of the X‑Men franchise, but it’s one that has not aged particularly well.

X‑Men: God Loves, Man Kills is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Book Depository), and here (Chapters-Indigo).

1: Actually, synthesizing vitamin C is a superpower that I happen to think would be spiffy, but have not seen in any comics. Professor X tended to recruit teens with offensive or defensive super-powers, poor Cypher being a notable exception. Perhaps the Professor overlooked many useful mutations.

2: Stryker’s minions may have developed this technology. Alternatively, the fact the arguably most prominent mutant is a grotesquely powerful telepath may inspired a lot of people to work on psi-blockers.

3: “Accident?” you ask. “What about the two missiles? And the gunfire you didn’t mention? What about eyewitnesses on Central Park Drive?” It’s possible the NYPD did not send its best.

4: “What about dental records?” you ask. The evidence that the NYPD assigned to the case actually cared what happened to some mutants is non-existent. You’ll be happier if you don’t google police + no human involved, but this may be an example.

5: Marketing was not one of Magneto’s superpowers.

6: Somewhat unusually for speculative fiction of this era, thirteen-year-old Kitty “Sprite7” Pryde’s determination to win the heart of the much older Piotr “Colossus” Nikolayevich Rasputin gets pushback from other X‑Men, due to the age difference.

7: And many other code-names. It’s as if she were thirteen and still figuring out who she was.

8: Sprite can become intangible and immune to bullets, but presumably the cop did not know that.