It May Be Raining

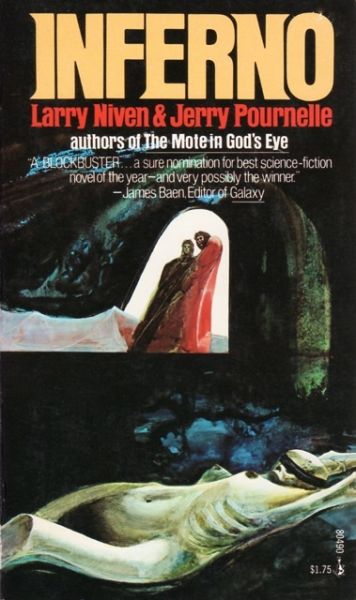

Inferno

By Larry Niven & Jerry Pournelle

15 Feb, 2020

Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle’s 1976 Inferno is the first installment in their Inferno series.

Allen Carpentier’s unremarkable science fiction career ends when an attempt to win the love of fans ends with a drunken plummet from an open window to the sidewalk waiting below.

Allen is very, very dead. He is also still conscious, which is something of a surprise to this agnostic SF writer.

After an immeasurable time spent in a featureless void, Allen appeals to God (in a figure of speech, but apparently that counts). He is freed from limbo and finds himself on a plain covered with small brass jars. Waiting for him is the oddly familiar Benny, who offers to guide Allen out of the realm in which he is imprisoned: the Christian Hell.

Allen is initially quite reluctant to accept Benny’s claim. It’s more likely that Allen has been cryogenically frozen, woken by some fantastically advanced civilization, and dumped into an unpleasant theme park. That’s just science! Unfortunately for Allen, the facts on display do not support this comforting theory. In the end, he very reluctantly admits he is damned and in Hell.

Not all is lost, however. Benny claims there is a way out of Hell and that he has previously led others out. Alarmingly, that path leads deeper into Hell. To escape, Allen will have to brave all the dangers Hell has to offer.

~oOo~

There is an unnecessary sequel to this book whose only utility is to show that a sequel to a successful book may not be very good.

This is the SF book that features a sunnily charitable take on Benito Mussolini. SF loves its jackbooted thugs. Of course, Benito is in Hell, so the portrayal doesn’t entirely overlook his little quirks, but if one were to imagine a spectrum of possible Benito Mussolinis, this one is way the heck over towards the misguided extremist end. He meant well.

One of the greatest pleasures in imagining a Hell is filling it with people the authors are convinced deserve to burn in fires eternal. Niven and Pournelle embrace this tradition with enthusiasm, populating their Hell with the legions of those of whom the pair disapproved: shifty politicians, environmentalists, perverts, teachers who believe in dyslexia, delusional food safety advocates, and of course Kurt Vonnegut.

Unlike Dante, Niven and Pournelle generally refrain from naming actual people who are suffering in Hell. They’re either nameless stereotypes or fictionalized versions of their ideological foes. When real people are name-checked, they are either long dead or drawn from outside SF. Except Kurt Vonnegut.

Allen himself starts off as something of a dick, so keen on climbing his way up the greasy pole of SF fame that he’s willing to tolerate the company of its loathsome fans. Presumably this is to ensure the reader understands how Allen ended up in Hell. The notion that an author could yearn for accolades of people they thoroughly despise1 is too absurd to consider seriously.

This being an early Niven and Pournelle work, there are occasional elements of interest. It’s not all “and then all those people who disagreed with me found themselves nipple-deep in burning tar.” Not all, but a lot of it is. It’s a bit odd, then, that this was so favourably received. It was nominated for both the Hugo and the Nebula. For reasons that are not clear to me, the book then fell out of print for twenty years. It has been republished but it doesn’t seem to have stormed the bestseller list. I went looking for a recent edition and found this way down the list of books titled Inferno.

Inferno is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon US), here (Book Depository), and here (Chapters-Indigo).

1: Any resemblance to Sad Puppies is coincidental.