It takes a thief

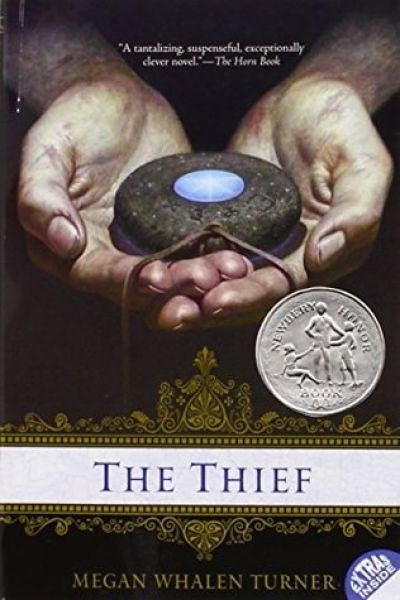

The Thief (Queen’s Thief, volume 1)

By Megan Whalen Turner

5 Jan, 2016

0 comments

I admit I approached The Thief, Megan Whalen Turner’s 1996 novel, with trepidation. Not only was it a Newbery Honor Book (with all that implies), but I had previously read and disliked its sequel The Queen of Attolia. Having read and enjoyed The Thief, I am forced to consider that perhaps I misjudged The Queen of Attolia.

By his own testimony, Gen is the greatest thief the city-state of Sounis has ever seen. That same testimony appears to mark him as somewhat less than the most astute thief in Sounis, because Gen made that boast to a client who turns out to be a government agent.

By the time the book opens, Gen has spent a fair time in a dank prison, contemplating escape options. Gen can steal anything but not, it seems, his own self from a secure dungeon.

An opening to freedom appears in the form of the King’s magus, who needs a talented thief.

Someone who can steal a magical icon straight out of a fairy tale.

The polities of Sounis, Attolia, and Eddis are linked by history and geographic proximity. Sounis and Attolia are divided by a mountain range. The one break in the range is occupied by Eddis, a monarchy that has until now resisted all attempts to conquer it. Eddis’ immunity to invasion is not shared by its two neighbours, both of whom have been conquered by a succession of invaders, since driven off (although not before transforming the local culture). All three states (Sounis, Attolia, and Eddis) now face a far greater threat: the seeming invincible Medes. Together, the states might stand against the Medes; a regional alliance would seem advisable. However, the distrust between the three states seems insuperable. The magus has conceived of a cunning ruse that will force an alliance. Which is where Hamiathe’s Gift comes in.

Hamiathe’s Gift dates from the age of the old gods. Whoever possesses it may claim Eddis’ throne. The Gift was hidden away long enough ago that most people consider it a mere myth; the magus believes that it is real and thinks he knows where it is. If he can recover it, then Sounis can blackmail the Queen of Eddis into marrying the King of Sounis. Sounis’ army could then march into Attolia and unify all three states.

The magus believes that the Gift is hidden in enemy territory. in a place where it might be recovered by a small, stealthy, expedition. It should be easy to sneak into enemy lands, recover the Gift, and flee to safety. No problemo. The problem will be extracting the Gift from its hiding place. Only a master thief can carry that off … and there’s a master thief vegetating in the dungeon. How convenient!

The magus is fairly sure that others have figured all this out and tried for the prize. He knows that no one has survived any such attempt. How to steal the Gift is a problem for which the magus has no answer. Something he leaves to lucky Gen.

Gen can regain his freedom, but only at the cost of risking his life.

~oOo~

This is not a typical Newbery book: no dog dies of rabies, no best friend drowns in a shallow creek, and Charlotte does not die all alone at the fair. Well, there are a few sad moments in this book, but nothing as sudden and brutal as the death of the protagonist or the protagonist’s close friend. Or their pet.

This book is set in a secondary world inspired by Greek history. The whole range of Greek history, from the Greco-Persian Wars to the Byzantine era to the 19th century wars of independence. It’s a jumble melange, in which Bronze Age gods share the world with pocket watches and gunpowder.

I had to tell you about the magus (not named in the book) to hint at the plot, but the actual protagonist is Gen. He’s not the nicest fellow ever; his fellow murder hobos adventurers put up with his uncouth manners and disrespectful demeanour only because they need his skills. Gen is a rogue. The narrative often reminded me of the first-person smart-ass of a Zelazny or a Chandler novel, as Gen relates the events of the novel with the easy confidence of a man who has convinced himself he knows more than the people around him, despite that whole “was chained to a wall when we first met him” thing.

The book seems linear enough, right up to the moment when surprising revelations start to tumble on the reader’s head1. Now, you might wonder why, if I had read the sequel, I was surprised by the big reveals. The answer is that I seem to forgotten virtually everything about the second volume save for the Queen’s cutting remark near the beginning.

I wasn’t expecting to enjoy The Thief at all, let alone as much as I did. I really must reread The Queen of Attolia to see where I went wrong.

The Thief may be purchased here.

1: One of the surprises involves something that does not happen: this is not one of those novels in which archaeological research is indistinguishable from suicide.