Jet Packs and Laser Guns

Space Opera

By Edward E. Simbalist, A. Mark Ratner & Phil McGregor

5 Jun, 2022

Edward E. Simbalist, A. Mark Ratner, and Phil McGregor’s 1980 Space Opera is a venerable science-fiction tabletop roleplaying game. It was published by Fantasy Games Unlimited. The writers’ intent was to provide an all-in-one set of rules that would cover nearly every contingency SF gamemasters might encounter.

Which it does, but not especially well.

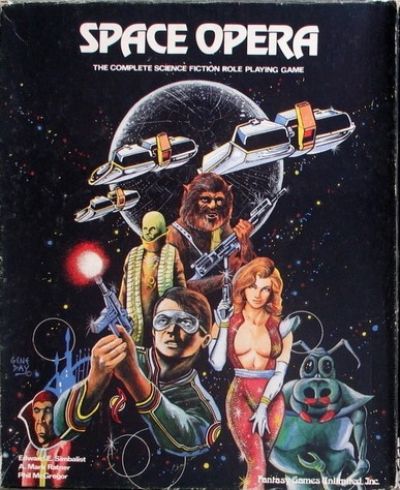

The first thing potential Space Opera purchasers would have noticed was the box art, which promises Star-Wars-type adventure. My copy being a first version of the black box printing (I don’t think the versions were called editions), that meant that the woman on the cover was wearing a body stocking with what TV Tropes calls Absolute Cleavage. A later version added a shirt.

The otherwise revealing original cover suggests that while the woman definitely had breasts, she might have lacked nipples. One must conclude that the target audience was boys and men. This conclusion is supported by the text, which (with few exceptions) assumes that player characters would be male (even if from a variety of species).

Within Space Opera’s reasonably sturdy box (mine has survived forty-two years) were two saddle-stitched booklets, labelled volume one and volume two. While saddle-stitching has gone out of fashion, these binding are as sturdy as the box; they barely show any wear1. Both are illustrated. The artwork (by Gene Day) is typical of the period2, if not the best that Day could do.

Volume one is ninety-two pages long and covers character generation (CharGen) as well as other subjects. Volume two is ninety pages in length and focuses on equipment and combat.

There are no indexes. There are many tables. So many tables. Each volume has a detailed table of contents, which isn’t necessarily correct; I noticed at least one instance in which the page numbers were wrong.

There are numerous typos and spelling errors (“steller” for “stellar” demands special recognition) and the text’s approach to margins is best described as inconsistent. The authors’ prose is bold and idiosyncratic, with a marked enthusiasm for jamming two capitalized nouns into one word (camel-caps, a fad of the 1980s) and for emphasizing phrases with quotation marks.

First-time readers will notice very early on that the book is organized by what one might call the stream-of-consciousness method. Characteristic generation and characteristic definition aren’t next to each other. Combat charts appear haphazardly. Without an index, the reader has no quick way to find applicable rules in ambiguous situations.

The authors do their best to provide a framework3 that facilitates emulating the most famous space operas: Lensman, Star Wars, and the like. In fact, their inspirations are so obvious, starting with cover art that is very much like the first Star Wars poster, it is in retrospect astonishing that FGU never got a cease-and-desist letter from the Smith Estate or from LucasFilms. I suspect FGU was protected by obscurity: companies only go after IP infringements that they notice4.

While we did play a few sessions of Space Opera before moving on to other games, I am not entirely certain there’s a playable game here. Our success in playing may simply be an example of applied pareidolia (seeing in the game play what one expected from other games, just as one can see a face in the markings on a tortilla).

Still, the game is interesting to me for reasons other than playability. It is a fascinating historical artifact. For example, it was one of the few games FGU published that had anything like decent support. FGU owner Bizar took some time to grasp that RPGers didn’t want to do all of their own design work. This was a point of view that was not in any way peculiar to Bizar: the field was only four years old when the game was commissioned, and just six years old when Space Opera came out. Creators were still experimenting to determine what worked and what did not. As well, FGU did not have in-house designers, so the availability of supplements was to a large degree dependent on how energetic the relevant freelancers were feeling. In the case of Space Opera, they were very energetic, so there was ample material to purchase and adapt to better systems5.

As well, the game reflects the technology available at the time. The authors lived on opposite sides of the Earth without anything as convenient as email to move files back and forth. They had to rely on postal services to ship paper. The rulebook definitely needed more polish, polish that might have been possible if the authors hadn’t had to cope with the USPS and the Australian postal service.

Close inspection suggests that the number one was represented in some places by 1, and in others by l. This likely reflects the use of typewriters when the text was being written. While home computers did exist in 1980, there was nothing like the desktop publishing software that came along later in the decade. Thus, any spellchecking relied on the mark-one eyeball; cutting and pasting involved actually cutting paper and pasting it down. This is probably why the margins are so inconsistent: no software to manage margins.

There was a second version. I do not have it and cannot say how well it addressed the glaring problems in the first printing. Well, one problem was addressed: the art was tweaked to reduce the cheesecake factor.

Although FGU had a rather colourful history in the 1980s, 1990s, and beyond, a game company with that name currently exists. Whether it is best seen as a continuation of the original company or the old company’s owner’s new company using an old name to squat on rights that should have long-ago reverted to the writers is an interesting question that I invite you to discuss only in terms that won’t rope me into the subsequent lawsuits. Whatever the true status of the matter, there is an FGU that sells FGU products. Space Opera is available here.

I should add that I cannot recommend that gamers play this game now: it handles nothing better than modern games and a great many things worse. However, persons interested in the history of the field may want to take note of Space Opera.

1: Of course this may be because I probably didn’t reread the rulebooks all that often … if at all.

2: It was a golden age of “someone’s cousin who draws a bit” getting professional illustration opportunities they might not have had otherwise. There was an efflorescence of often spectacularly awful art. I do like to think that some talented artists may have emerged from those garage-band days of RPGing. Suggestions?

Speaking of weird connections, until I did background research on this, I had no idea FGU’s owner Scott Bizar was for a time Chaosium founder Greg Stafford’s brother-in-law. Forty years ago gaming was very small community.

3: A mid-Cold War, slightly right of centre framework, judging by the text’s descriptions of socialism. Yes, if you want to fight Space Commies, you can. In fact, if you use the official setting it may be hard not to.

4: Adhering a smidge too close to inspirational material was not unique to Space Opera’s writers. Many GMs used that approach enthusiastically. I am thinking here of the light-saber-wielding Protector-stage Jediwe encountered in one particular Traveller campaign.

5: At some point I need to review GURPS, an RPG whose mechanics I didn’t like all that much, but whose world books were often extremely useful.