Later’s Better Than Never

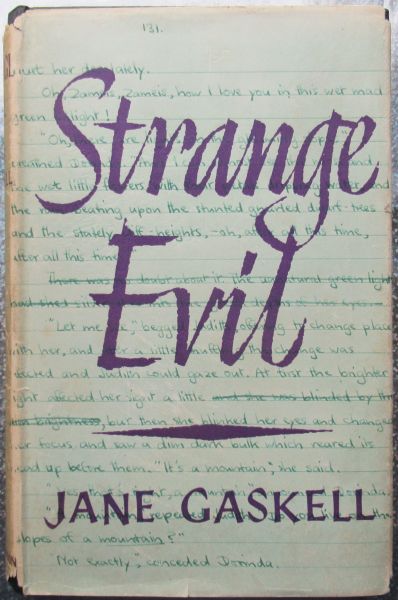

Strange Evil

By Jane Gaskell

12 Sep, 2023

0 comments

Jane Gaskell’s 1957 Strange Evil is a stand-alone free love portal fantasy.

Professional model Judith Henderson is enormously put out to discover that her cousin Dorinda has invited herself to stay with Judith. This is the first Judith has heard of Dorinda, Dorinda’s mother having vanished following a scandalous marriage to an Italian aristocrat. Judith has little choice but to host Dorinda while Dorinda visits her mother’s birthland.

Judith soon discovers that there’s an upside to the unwanted guest. The guest has brought her fiancé, Zameis, with her. Judith is immediately besotted with Zameis.

Judith is somewhat torn over whether she should act on her attraction to Zameis. On the one hand, he is already Dorinda’s. On the other, Judith undoubtedly loves him more than does Dorinda, so he should be Judith’s on purely utilitarian grounds. It’s quite the ethical pickle!

And then … Judith happens to see Zameis’ antennae. It seems the deceased Italian nobleman was no Italian but a faerie lord. Zameis is a faerie lord as well. This poses a problem for Dorinda (also faerie) and Zameis, as Earth folk are not supposed to know about faeries. The easiest solution is to take Judith with them when the couple returns to their faerie realm. Judith is easily convinced to accompany them.

The faerie realm is a land of (decorously off-stage) free love and physical pleasures. One might expect those to distract Judith from having abruptly abandoned her home world. What actually captures her attention is the surprisingly universal conflict between the Haves and the Have-Nots.

Dorinda’s people, the Internals, worship their odd god and embrace their particularly decadent (but off-stage) excessively free love within the Mountain, source of certain life-giving emanations. The Externals, those who rejected the new god, were forced to leave the Mountain and live as outcasts in the surrounding forest. The catch: without those emanations the Externals are languishing and will soon perish.

The Internals have very little interest in helping their External relatives. True, Externals can make a case that tradition and law support their claim to access to the Mountain. The Internals have power on their side, so why waste time talking to outcasts when that time could be used to pursue decadent pleasures?

Having tried reason, the Externals can either accept inevitable death or begin a war they will probably lose. They opt for the second, almost certain death being preferable to certain death. Judith seems powerless to help either side … but she has the greatest power of all!

~oOo~

As you may know, Gaskell was only fourteen when she wrote this (although somewhat older when it was published; writers are almost never younger when books are published than when the books are written). I wasn’t sure what I would find inside the covers. A protracted struggle between desperate have-nots and powerful haves who negotiate in bad faith came as a complete surprise.

One of the important differences between the Internals and Externals is religion: the Internals worship a new god, which takes the form of a giant Baby, and the traditionalists do not. The Baby never makes a strong case that it deserves worship. However, worshipping Baby gives the Internals a justification for their monstrous acts.

I am sure there are no real-world parallels here.

Product of its time warning: Judith compares the decadent religion on the Internals to Hinduism. The grounds of the comparison are rather vague, as though Gaskell assumed readers would know what she had in mind or possibly as though Gaskell was a young teen and bit confused about other people’s religions.

Judith is surprisingly judgmental about other people’s love lives for someone who spends the first part of the book pining after a man who has a fiancé, and the last part of the book pining after a different man who also has a fiancé1. Judith is perfectly happy to pose nude2 and to embrace a certain level of free love, but there are limits! At least for other people.

The book contains all the elements needed to produce a work of superlative sensuality, unparalleled depravity, and enthusiastic licentiousness, save for one. The work is surprisingly vague about what goes on during the carnal revels. Readers may suspect this had something to do with the author being a fourteen-year-old girl when she wrote this. Perhaps the prudish customs of that distant time (the 1950s) would also help account for this. A modern fourteen-year-old with access to the net could probably write much more convincing sex scenes. The result: the novel is a PG-13 cut of an inherently NC-17 tale.

While Strange Evil has its flaws, this short novel is pleasingly energetic, with some unexpected depths. It seems a pity that readers curious about it will have to search for used copies or appeal to a well-stocked library, as Strange Evil has been out of print for decades.…

At least in our dimension.

1: Dorinda is lucky Judith’s eye wanders once she arrives in faerie. This is all to the good for Dorinda, as the author resolves the ultimate romantic triangle by killing Judith’s rival. The locals would no doubt happily share loved ones, but the author chose to complicate the plot.

2: Early on, the novel establishes that Judith is the good sort of nude model, which is to say the sort who shows up when and where she said she would, and not the bad sort, who do not. There really need to be more secondary world fantasies about the importance of punctuality and I was sad to see that plotline get dropped.