Let Me Be Lighter

Ariosto

By Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

20 Jun, 2021

Chelsea Quinn Yarbro’s 1980 Ariosto is a standalone mundane alternate history novel (but one which contains within itself a fantasy alternate history novel).

Italy’s warring states have set aside their mutual enmity in the name of common defence. The Italia Federata protects all of its member states from foreign aggression, whereas formerly each principality and republic could rely only on its own strength and that of an ever-shifting network of allies.

Ludovico Ariosto is but a poet, not the Il Primàrio who expected to keep all of the Federata’s saucers in the air. Il Primàrio Damiano de’ Medici is, however, Ariosto’s patron. Italy’s problems are Damiano’s and by the transitive property, Italy’s problems are Ariosto’s.

Small wonder the poet finds escape in fantasy.

In the world of the poet’s imagination, he is a grand adventurer, the man who tamed a hippogryph, the hero who defeated the Great Mandarin in single combat. Now his talents are needed in the New World, where Nuova Genova and its Cérocchi are imperilled by the Fortezza Serpente, the dread sorcerer Anatrecacciatore.

In the real world, Ariosto is dragged into the troubled world of international politics thanks to his patron. Someone must greet the Tudor embassy to the Federata, as Damiano juggles Italy’s need to maintain contact with Henry VIII while at the same time not offending the pope Henry with whom English Henry has fallen out. Ariosto is the obvious choice. Consequently, the poet becomes privy to state secrets, namely that Henry is working on an alliance with Moscow that may upend the current international order.

In the poet’s fantasy, matters are hardly better. Anatrecacciatore commands powerful magic. His allies include giants of flint and ice. His army is vast and those who oppose him seemed doomed to miserable ends. Nevertheless, Ariosto is determined to take part in the common defence, if only to die facing the enemy than perish during cowardly flight.

In the real world, the Federata’s member states are all jealous of each other. Each head of state is eager to push the limits of their poorly defined positions1within the new nation-state; each is eager to see former rivals humble. Henry VIII’s embassy provides the pretext for potentates to claim affront at the manner in which the diplomatic mission was handled. This cannot serve Italy well, but the Federata is too young for rulers to have accustomed themselves to thinking of the whole region as a unified entity.

Il Primàrio Damiano de’ Medici is resolute in his determination to steer his young nation towards unity and mutual assistance. Unfortunately for Damiano and those standing too close to him, this makes him an impediment to be removed.

~oOo~

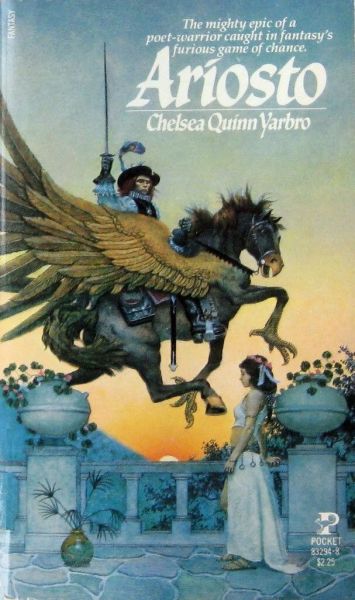

Here is a better version of Maitz’ cover.

I am not up on my Italian history and I suspect I missed a lot of in-jokes.

This alternate history is one where Europe is dabbling in negotiation rather than the usual backstabbing. It’s not just Italy; it’s a minor plot point that the War of the Roses was ended with a compromise (Richard naming a Tudor his successor) than a battle. Or perhaps that should be “dabbled” in the past tense: Henry VIII is still a willful autocrat determined to have a male heir at any cost to England’s relations to Church and Europe, while the Italian heads of state seem not to have understood that joining the Federata meant being one part of a whole as opposed to the most significant part of the whole.

Modern readers may find that the behavior of certain regions within the Federata recalls the UK’s attitude towards the EU. Bear in mind this novel was published forty-one years ago, long before the EEC became the EU. In fact, there are a number of nations, federations, and international arrangements in which (subsequent to this novel’s publication) divisiveness proved stronger than unity (Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, to name a few), as well as a great number that fell apart prior to publication (the United Arab Republic, the West Indies Federation, and Gran Columbia, to name a few). There is a lesson here, perhaps only that it’s amazing we’ve managed to stitch together any nations larger than small counties.

Having permitted her nations their moments of community spirit, Yarbro then explores reversion to the mean. There are more ways for Italy to fall apart than there are for it to remain together; most of those divisive paths have lamentable consequences for Ariosto and his patron. To put it another way, this is a tragedy wherein an initial triumph is only the necessary precondition for an epic defeat.

Yarbro’s structure is interesting. Ariosto may be trying to escape his daily life with his heroic fantasy, but the troubles of one are reflected in the other. Ultimately, the author manages to unify the two narratives in an unexpected way. I don’t own a lot of Yarbro books, but this fascinating effort clicked for me. Readers appear to have liked it. Ariosto was nominated for both the World Fantasy Award and the coveted Balrog,

As far as I can tell, even though Open Road Media and SF Gateway did ebook editions of Ariosto as recently as 2014, Ariosto is out of print.

1: Unifying before hammering out the exact details may have been necessary to unify at all. The ambiguities allowed each ruler to kid themselves that nothing significant would change. The unification then faced serious implementation issues.