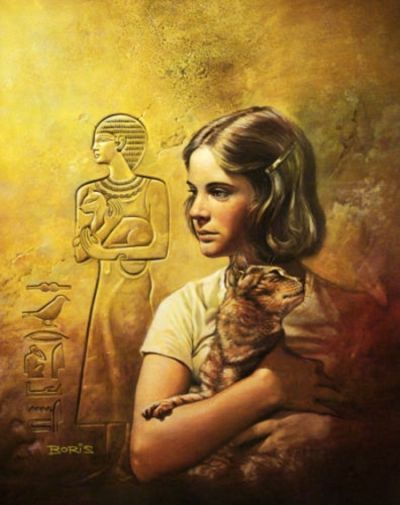

Life Ain’t What It Seems

Cat in the Mirror

By Mary Stolz

14 Aug, 2018

0 comments

Mary Stolz’s 1975 Cat in the Mirror is a standalone young-adult novel.

Erin Gandy is a grave disappointment to her mother Belle; she is deficient in the feminine virtues appropriate for women of her class. Neither pretty nor popular, Erin might well one day end up an academic or worse yet, a feminist. At least Erin can turn to her schoolmates for solace. Or she could if they did not despise Erin even more than her mother does.

Spoilers for a book more than forty years out of print.

Erin does at least have a decent relationship with her father. Like Erin, Peter Gandy is trapped in a world where his dreams must take a back seat to reality. He would love to be an archaeologist, but what he actually does is deal in livestock hormones. The money Mr. Gandy makes is enough to win his wife’s grudging toleration, though not her respect.

Seti Gammel is an Egyptian transfer student. While modern-day Egypt is nothing like Mr. Gandy’s beloved ancient Egypt, her museum forays with her father are enough to build a bridge between Erin and her schoolmate. In a better world, this might have also led to a reconciliation with the other students, but as Erin soon learns, being friends with the exotic new student doesn’t make her any less weird in her classmates eyes.

Distraught after overhearing a spiteful conversation, Erin runs headfirst into an obstruction and knocks herself silly.

At which point we segue into something that may or may not be a different story.

Irun is a sad disappointment to her mother Bel; she lacks the virtues proper to an Egyptian girl of rank. Irun at least enjoys a close bond with her father Perub, who is far more tolerant of his daughter’s eccentric desires than one would expect of a high-ranking servant of the Pharaoh. Still, she doesn’t need further complications in her life. Irun does not need a demon named Erin sharing her head.

Especially not a demon whose un-Egyptian ways could easily get Irun and her entire household executed by the boy Pharaoh.

~oOo~

It is possible that the Irun section is a hallucination that Erin suffers thanks to a blow to the head. In that case, the parallels between Erin and Irun’s lives are because Erin is drawing on her own experiences.

It’s also possible that Erin have been given a glimpse of a past incarnation, in which case Erin, Belle, and Peter have been locked into variations of the same dysfunctional relationship for thousands of years.

Peter Gandy has a pretty sunny view of what life under the Pharaohs was like, one that may not be the consensus view of ancient Egypt. The reincarnation interpretation of the plot suggests that Peter has been assuring himself for millennia that the lower orders like their lives of endless labour. How curious that Peter believes something that is so convenient and reassuring.

I am not sure which boy Pharaoh the boy Pharaoh in this book might be. The text seems to refer to him by his titles, and his sister-wife’s name, Mery-ti, is a common one. An ancient Egyptian might argue it doesn’t matter which Pharaoh this one is. They’re all gods among men, not people you want to annoy by denying them even their most trivial desires.

Both Erin and Irun have the good luck to be born into the upper classes, although neither of them are able to appreciate their good fortunes. Money doesn’t shield them from their mothers or from people their own age. Still, at the end of the day it’s better to be rich and miserable than poor and miserable.

The happiest people in this book are the stupidest, because they accept their positions in life without wondering if it’s fair that they have so much privilege. The only discordant notes in the life of Erin’s mother Belle are caused (she thinks) by other people; those with unfashionable physiques, those who think too much, servants who want higher wages. The other kids at Erin’s school are easily satisfied by lavish allowances and a blind eye turned toward their bullying ways. Simple lives, but rewarding ones.

(In both worlds, the servants know that life isn’t fair. They also don’t expect it to be fair. They just hope that they aren’t fired or thrown to the crocodiles.)

It is odd this book appears not to have sold well and to be obscure today. The premise — an eccentric girl trapped in a school rife with status-obsessed bullies — is one that I would think would have broad appeal. Perhaps the issue is that the author eschews the obvious morals and comforting conclusions of so many works aimed at younger readers.

Erin’s insight into a dysfunctional family of the far past might allow her to escape the same dysfunction in the present. It’s not clear that it will, because the book ends as Erin is still digesting her experiences.

Cat in the Mirror is out of print, although Amazon has used copies here.