Like Dragons in the Dead of Night

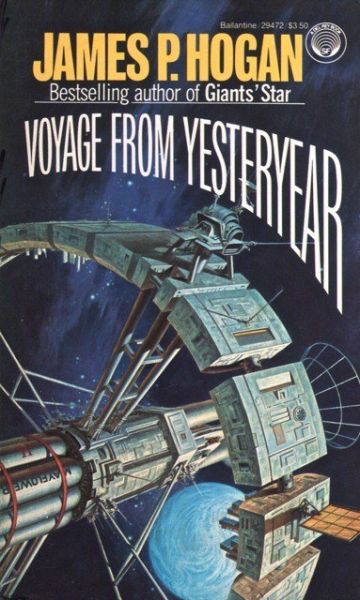

Voyage From Yesteryear

By James P. Hogan

16 Apr, 2019

James P. Hogan’s 1982 Voyage from Yesteryear is a standalone science fiction novel.

Faced with seemingly inevitable nuclear war in the near future, the North American Space Development Organization and its Asian partners decided to take the bold step of re-purposing the SP3 interstellar probe. Five years before its 2020 launch, the probe was redesigned to deliver human life to Chiron, the habitable world in the Alpha Centauri system. But there’s a catch.

Sending adults is impossible. Instead the Kuan-Yin carries with it encoded genetic information and machines designed to create and raise human children. It’s a gamble, but the alternative is hoping that nuclear war doesn’t manage to drive humanity into a new dark age or even extinction.

The probe succeeds: a generation after its launch, humans in increasing numbers call Chiron home.

World War Three breaks out a year after Kuan-Yin leaves. It’s far worse than the brush-fire exchange of 1992. Somehow, civilization survives. The New Order rebuilds America, this time without any corrupting pretense of equality and social mobility. Conscious that its rivals in Europe and liberal Asia have cast avaricious eyes on Chiron, New Order America dispatches an expedition on a twenty-year journey to reach and claim Chiron for the New Order.

Terra and Chiron have been in constant contact since the Kuan-Yin established its colony. Forty years into human occupation of Chiron, it is clear to the New Order that something has gone horribly wrong with the colony. There is no hint of the hierarchies necessary to any sensible society. Instead, the Chironians seem to think possession of an expanding economy with ubiquitous automation and limitless resources means that they can each do whatever strikes their fancy.

It’s America’s duty to cure the Chironians of this delusion. If simple logic fails, the Mayflower II has weapons ranging from sidearms to nuclear city-busters. Chironians appear to have no military-industrial complex. Their choices are submit to their betters or die.

It all seems so simple as the Mayflower II approaches Chiron. The American starship fails to take into account the one weapon the New Order cannot resist: the lure of freedom.

~oOo~

I would not be at all surprised to discover that Hogan had a dog-eared copy of Eric Frank Russell’s “And Then There Were None.” The manner in which the New Order finds its staff evaporating into Chironian society as soon as they encounter it is very reminiscent of EFR.

This novel has its flaws. Hogan’s prose, for example, was never better than serviceable and it is often flat-out clunky. As well, in accordance with the grand traditions of utopian fiction, most characters are either righteous or villainous. (To be fair, there are some New Order elites who changes sides. Such character arcs are never a given with Hogan.) The characters are cardboard … though some of them appeal to beloved stereotypes. The contingent of the New Order military who save the day is a collection of rogues and oddballs notorious for subverting military discipline.

In retrospect, Hogan’s decline into holocaust denial may be foreshadowed by his assumption that, like most governments, the New Order authorities will spew endless self-serving lies about history and about groups currently the designated Enemy. That Hogan would become a denier wasn’t obvious in 1982.

Still, the novel has its virtues. Hogan prudently selects as his viewpoint characters New Order Americans rather than Chironians. This allows him to keep a few cards up his sleeve while facilitating lengthy explanations of how Chironian utopia works. If there’s one element on which all utopian fiction is dependent, it’s leading newcomers around to explain how, e.g., the laundry gets done in the World of Tomorrow1.

Voyage from Yesteryear is unusual in that virtually all SF of this sort that sees print is American right-wing libertarianism, long on gun-waving and gold-buggery. Hogan, on the other hand, is much closer to Iain M. Banks than American libertarians, which may be the first time that phrase has ever seen print: his anarchy is so rich they don’t need to track resources2. They are also essentially reasonable people, having been raised by good old sensible robots3 rather than Terrestrial ideologues. Nobody need be particularly concerned that your average Chironian can set their hands on WMDs if the whim takes them.

This is probably Hogan’s best novel. His earlier stuff was much rougher and his later… well, best not to dwell on some matters.

1: Robots do it, presumably. I really need to review William Pène du Bois’ The Twenty-One Balloons, which spends more time dealing specifically with the issue of laundry that I expected. Granted, I expected “no time at all.”

2: At some point they will run out of room, but they are sure that they will think of something.

3: I was hoping I’d have an excuse to reference Clarke’s Songs of Distant Earth and here it is. Songs shares with Yesteryear the conceit of settling a distant world with robotically-raised children. As does Chiron, the colony that results lacks some culture traits commonly found on Earth (in Clarke’s novel, this is planned rather than happenstance). Clarke’s new world isn’t a shiny, perfect utopia. Everything is a bit shabby; there are lots of human foibles on display; but people are happy enough. The Clarke novel (1986) was published after the Hogan (1982).