Like The Ocean

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Captain Nemo, volume 1)

By Jules Verne

13 Oct, 2024

Jules Verne’s 1869 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, originally published as Vingt mille lieues sous les mers, is one of Vernes’ series of Voyages extraordinaires, or in the Anglophone vernacular, Awesome Trips. In modern terms, it could be described as a proto-technothriller or possibly a proto-hard-SF novel.

Repeated encounters with a mysterious oceanic phenomenon inflame public interest and alarm. Whatever the object is, its range is global, its size prodigious. The American government dispatches the frigate Abraham Lincoln to investigate.

Chance puts esteemed natural historian Professor Pierre Aronnax and his faithful assistant Conseil in New York at the same time Abraham Lincoln is in Brooklyn. Aronnax cannot turn down the invitation to join the expedition.

Aronnax’s suspicion is that the mysterious entity could be an immense narwhal. Aronnax’s educated guess is entirely wrong.

The world’s oceans are surprisingly large. It takes Abraham Lincoln some time to encounter the whatever-it-is. At this juncture, Aronnax’s career very nearly comes to an abrupt end. He is washed overboard. Faithful Conseil and Canadian whaler Ned Land leap overboard to save Aronnax. The trio’s prospects of survival appear quite poor.

Luckily for the trio, their quarry is no narwal, but a prodigious submarine. Surfacing near the trio, it offers what could well be a temporary salvation. Before it submerges, its crew notice the castaways clinging to the hull and bring them inside.

Aronnax and his companions are aboard the Nautilus. The Nautilus is the creation of its captain, Captain Nemo (No One). Nemo explains that Nemo and the entire crew have turned their backs on human society. Living off the ocean’s bounty, the all-electric1 submarine Nautilus has no need for contact with the nations that abused everyone on board. A necessary consequence is that Aronnax and company will have to remain on board for the rest of their lives.

On the one hand, no one cares to be a prisoner. On the other, the Nautilus is a surprisingly luxurious prison. As well, Nemo is a man of knowledge on par with Aronnax, and the Nautilus affords Aronnax knowledge of the ocean’s secrets he could not otherwise obtain. Best to defer escape attempts for now.

Aronnax’s increasing concern, old grudges, isolation and unquestioned authority take their toll on Nemo. Nemo is unquestionably brilliant, loyal to his men, and brave. Nemo is also more than a little mad and growing worse each day.

~oOo~

French Canadians will be interested to know that in Aronnax’s opinion, to call someone Canadian is to call them French.

The crew of the Nautilus, all male, are left in the background because they speak a conlang not shared with Aronnax, Conseil, and Land. Effectively, the three can only converse with Nemo. As Land has little to say to Nemo, the situation is particularly trying for him.

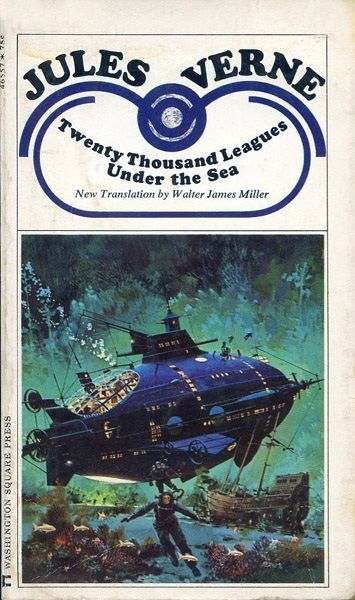

I first read my Washington Square Press edition of this novel half a century ago2. I remember being struck by the introduction, penned by translator Walter James Miller. Miller noted that Verne is regarded more warmly in the French-speaking world than in l’anglosphere. The reason, he said, is quite simple: Verne’s books were atrociously translated. Miller detailed the many shortcomings of previous translations, then set out to provide a better one himself. I think he succeeded.

Two narratives run in parallel in the novel. On a positive note, confident that his guests will never be able to reveal his secrets, Nemo describes the Nautilus in great detail, as well as revealing his covert logistical facilities. Nemo also shares his knowledge of the ocean with Aronnax, who appreciates that he is learning things that he could not have learned otherwise (given the limitations of his previous research methods).

Verne clearly did considerable research into what was known of the oceans at that time, as well as doing research into contemporary tech. He imagined inventions that would make the Nautilus possible. He was determined to share the results of his research with readers. So, in addition to writing proto-SF, he may have deployed the proto-infodump.

On a less positive note, Nemo makes a strong case against vengeful brooding in a community of irritable, isolationist conlang enthusiasts, Not a productive therapeutic strategy. When the trio first encounter Nemo, he is arrogant and aloof, but merciful. As the journey continues, it becomes clear that Nemo is erratic and inconsistent. He laments the greedy extermination of whales in general, while conducting a vendetta against sperm whales in particular. Towards the end of the novel, Nemo starts taking increasingly perilous risks3 and appears willing to commit murder.

This novel was a best-seller in its time (and has been ever since). Verne was somewhat of a humorless infodumper, but the book was also readable for its humor. His characters take themselves very seriously, but Verne takes a much more distanced view of their foibles. Oh, and it’s a thrilling read.

The introduction to this edition remained in my memory because it was the first time that I had been reminded that the quality of a translation mattered. Miller made clear it clear to a much younger me that any translation can be as much the work of the translator as of the original author.

A comparable edition of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea is available from the Naval Institute Press (here). Other editions are available from other booksellers, but I am not sure of the quality of the translations.

1: The Nautilus was not nuclear-powered, whatever Disney claimed in their film adaptation.

2: This edition was illustrated by Walter H. Brooks, an illustrator of some note. Not the Walter Brooks who wrote Freddy the Pig.

3: Unless the risk-taking was Nemo’s way of allowing Aronnax and the others to leave in such a way that the world would think the Nautilus and all aboard were lost.