Love is the plan, the plan is death

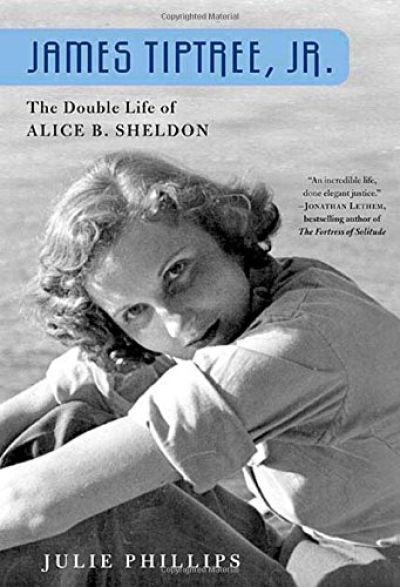

James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon

By Julie Phillips

13 Jul, 2015

0 comments

Anyone setting out to write a biography of a revered author could do a lot worse than to take Julie Phillips’ 2006 biography, James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon, as a model. It’s that good.

I suspect that most people who have heard of Alice B. Sheldon only know her as an author writing under various pen names, most prominently as James Tiptree, Jr. Yet authorship was only part of Sheldon’s life, only one of the identities she tried on over the course of her seventy-one-year life.

While Sheldon was aware of the science fiction being published in the early 20 century [1], she doesn’t seem to have been tempted to become an SF author herself — at least at first. Instead, uncomfortable with the constrained roles then allotted to women, she moved from life to life as a child celebrity, wife, divorcee, artist, critic, WAAC, WAC, work for the US intelligence community (although not to the extent fannish myth would have it), marriage to the more suitable Ting, a foray into the sciences, and finally, in her fifties, her emergence as not just one pseudonymous science fiction author, but several.

Sheldon lived under restraints that made it unlikely that any given identity she adopted would be a perfect fit. She lived in a society even more patriarchal than ours, a world that regarded women as second-class citizens. They were slotted into a few appropriate roles —save when wartime necessity required allowing women greater freedom (a freedom to be snatched away as soon as possible).

Women were also expected to be heterosexual, whereas it seems clear that Tiptree was well towards the lesbian end of bisexuality. She had male lovers and husbands but it was women who really rang her bell. Unfortunately, 20 century America wasn’t exactly a great time to be a lesbian. Or a woman, really.

Given her context and personality, it’s not that surprising that the authorial persona she adopted was male, or that losing that persona cost her professionally. It would be an overstatement to say that the effective death of James Tiptree, Jr. in the 1970s led to the death of Alice Sheldon in 1987, yet it seems obvious that adding one more injury to the burdens she already carried (her personal health, her struggle with depression, her husband’s decline) couldn’t have helped.

~oOo~

If you asked me to guess which editor discovered Tiptree, John W. Campbell wouldn’t have made my top five list. Maybe not my top ten. Color me surprised.

In the course of reading various biographies and autobiographies, I have been forced to conclude that writers cannot resist tidying up the facts of their lives, whether for greater narrative impact or in the service of egotism [2]. To rely solely on the version of their lives that writers freely offer is folly. Notes and quotations suggest that Phillips was a diligent researcher who looked beyond Sheldon’s own version of her life.

Considered as an artifact, this book is nicely put together and organized. Ancillary material includes a bibliography, fairly detailed chapter notes, and an index that passed all the tests I cared to throw at it.

Tiptree the science fiction author only appears about half-way through the book. Because of the impact Tiptree made on the field of science fiction, examining Sheldon’s life between 1967 and 1987 also provides an illuminating glimpse of science fiction history. I was a little surprised, given that Phillips isn’t one to spare feelings, how positively certain SF silverbacks come off as far as their relationships with Tiptree are concerned [3].

To be honest, while I am happy that I have my short shelf of Tiptree books, the impression left by the Phillips biography is that had Sheldon not lived in the time she did, if she had not lived in a culture in which virtually any ambition she might have had was denied to her or at least made far more difficult than it should have been due to her sex … she could have found more rewarding venues for her outstanding talents [4]. It was great for science fiction that Tiptree published her ground-breaking work, but was it such a great thing for Alice B. Sheldon? I don’t think so.

James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon is available from Macmillan.

1: Interestingly, there’s a period in Sheldon’s life when she dated someone named John Michel. Not that John Michel, not as far as I can tell. Probably for the best, because I cannot imagine that dating Futurians did much for a person’s security clearance.

2: I Asimov is an interesting case, wherein the image Asimov paints of himself does not seem to be the one he set out to create.

3: For example everyone (including me) mentions Silverberg’s ‘ineluctably male’ comment, but we rarely cite his comments following the revelation that Tiptree was Sheldon. Similarly, Ellison comes across as not as awful as he could have been; he has made it clear that he wasn’t the person who exposed the woman behind Tiptree.

I am bit sad to say that this is another biography that paints Fred Pohl in a somewhat unfavourable light. Given what else Pohl was publishing at this time, his reluctance to take a chance on Up the Walls of the World over issues of tense seems a bit odd.

4: There is a rather scathing discussion of how much benefit the world-traveling, accomplished Sheldon would have derived from mixing with the self-styled slans of the propeller beanie set.