Murderer Sitting Next To You

Asimov’s Mysteries

By Isaac Asimov

7 Apr, 2024

Isaac Asimov’s 1968 Asimov’s Mysteries is a mystery collection — mostly but not entirely science fiction — containing only stories written by Isaac Asimov himself.

Asimov tended to write stories in which the author plays fair with the reader. This is true whether the tale is a who-dunnit or a how-dunnit. The results are closer to Ellery Queen or Nero Wolfe than they are to Hammett or Chandler.

It’s probably best not to think too deeply about some of the mysteries and particularly about the role coincidence plays in several plots.

I had remembered that Asimov wrote many Wendell Urth stories; I was surprised to find that he wrote only four. Urth seemed like the sort of fellow about whom many stories could be told.

Some readers might advise skipping “I’m in Marsport Without Hilda,” but I disagree. I read that stinker and I don’t see why you should escape.

One story surprised me: the one about the bullied wife who resorts to murder. She is given sympathetic treatment. Asimov lets her get away with murder, which is not something one usually expects of his preferred genre of mystery story.

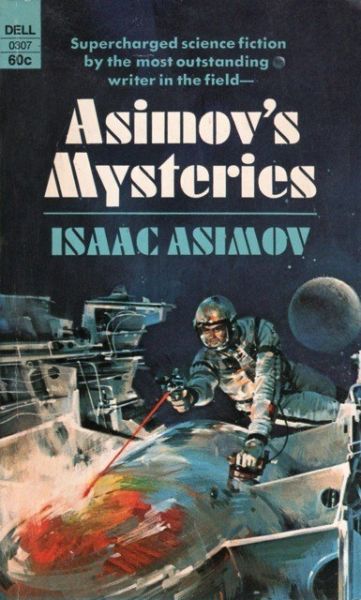

The collection was published in many editions with many covers. Of all the covers, my favorite is the John Berkey cover of the Dell Mass Market Paperback edition.

Final take: Asimov knew what sort of stories he wished to write. In most cases he had the skills needed to write them. (Bonus: the stories are accompanied by informative commentary from the author, commentary I found quite interesting.) The collection is a competent work of light entertainment. It’s dated, but something that readers might enjoy.

Asimov’s Mysteries is out of print.

Let’s go into detail.

Introduction (Asimov’s Mysteries) • [Asimov’s Essays: Own Work] • (1968) • essay

A brief discussion of SF mysteries. Having been assured that SF mysteries (ones that played fair by mystery rules) could not be written, Asimov then showed they could be by writing Caves of Steel.

Asimov doesn’t say exactly WHO claimed that SF mysteries were impossible. In the absence of info, I will do as I usually do and blame John Campbell. He was, after all, responsible for many odd pronunciamentos.

Note: both Clement’s Needle and Gray’s admittedly obscure Murder in Millennium VI predate Caves.

“The Singing Bell” • [Wendell Urth] • (1955) • short story by Isaac Asimov

Inspector Davenport recruits extraterrologist Dr. Wendell Urth to help solve the first Lunar murder. Urth is asked to assert that, in his professional judgment, there’s good reason to psychoprobe the main suspect. Can Urth prove the suspect had visited the Moon?

Some reviewers have compared the obese and travel-shy Urth to Norbert Weiner. I think it much more likely that Asimov’s model was Nero Wolfe. A choice perhaps informed by Asimov’s own aversion to travel.

In this commentary, Asimov notes that a reader informed him that he, the reader, had tried the method Urth used and found that it didn’t work. Ah, well.

A detail previously overlooked: Urth is initially consulted on a matter directly pertaining to his professional qualifications. This is true for the other Urth cases as well. Stark contrast with all the murder-solving actors, bakers, and caterers nosing their way into murder investigations.

Two details unrelated to the resolution of the story jumped out at me:

- Urth is called in because the state is highly constrained in its use of “psychoprobes,” a contrast to how truth machines were treated by contemporaries like H. Beam Piper;

- the suspect disposes of the spacecraft he used and any damning evidence in it by orchestrating a nuclear explosion in the upper atmosphere. One might expect authorities to be as or perhaps even more affronted by a deliberate nuclear explosion. The nuke is treated as a minor infraction, perhaps not even a misdemeanor.

“The Talking Stone” • [Wendell Urth] • (1955) • short story by Isaac Asimov

Urth is recruited to decipher the last words of a dying alien, who would know where a fission-fuel-rich asteroid might be found.

This is another story with details in the setting that bothered me. The alien and the human crew with it die because a technician, believing that the crew was breaking the law, sabotaged their ship’s power plant to help the authorities intercept it. This action played a direct (if unintended) role in the deaths of everyone on board. One might expect professional consequences for sabotaging vital equipment in deep space. Instead, the tech is praised for his insight and quick thinking.

“What’s in a Name” • (1956) • short story by Isaac Asimov

Did a librarian murder her co-worker and romantic rival? If so, what possible evidence could prove it?

This was a non-SF story, although it does involve chemistry. It’s a good thing that outrageous coincidence is part of the toolkit of mystery writers, because fewer murders would be solved without it.

Any scenes involving chemistry or academia come into sharp focus. It is almost as though the author had spent a lot of time in university chemistry laboratories.

The Dying Night • [Wendell Urth] • (1956) • novelette by Isaac Asimov

Which former classmate stole the dead genius’s ground-breaking paper? It’s up to Wendell Urth to reveal the culprit and rescue the secret of matter transmission.

This story reveals why psychoprobe use is restricted. In addition to the obvious privacy issues, if the subject is uncooperative probes can cause brain damage. Therefore, any given person can only be legally probed once. Yes, criminal do commit minor crimes in the hopes that they will be probed for that crime and not more serious crimes they might want to commit later.

“Pâté de Foie Gras” • (1956) • short story by Isaac Asimov

How is the goose that laid the golden eggs transmuting elements?

As pointed out, the goose isn’t just transmuting atomic elements, but it is doing so with a perfectly balanced energy budget. Given E=MC2, even a tiny imbalance would evaporate the goose.

“The Dust of Death” • (1957) • short story by Isaac Asimov

Which subordinate murdered the great, the obnoxious, the exploitative Llewes?

Judging by these stories, murder investigations frequently depend on the killer making some small error. Of course, as pointed out in the TV series Columbo, most killers are amateurs committing their first murder1.

I could not help but notice that Asimov depicts the situation with Llewes (who oversees a lab and steals all the credit for the work of the lab) in a manner that suggests he had personal familiarity with research credit hijacking.

“A Loint of Paw” • (1957) • short story by Isaac Asimov

The judiciary wrestles with the implications of time travel for statutes of limitations.

A slender excuse for an execrable pun.

“I’m in Marsport Without Hilda” • (1957) • short story by Isaac Asimov

A philanderer struggles to solve a drug-smuggling case in time to make his assignation with sexy Flora.

This is Asimov writing a sexy mystery. The goggles, they do nothing.

“Marooned Off Vesta” • [Brandon, Shea & Moore • 1] • (1939) • short story by Isaac Asimov

Three spacers will survive if they can use the limited resources of their wrecked spacecraft to escape orbit around Vesta.

This isn’t really a mystery; it’s a hard-SF story puzzle story.

“Anniversary” • [Brandon, Shea & Moore • 2] • (1959) • short story by Isaac Asimov

The trio of survivors from “Vesta” investigate the curious behavior of authorities after the mishap.

Asimov is as willing as Edgar Rice Burroughs to embrace outrageous coincidence. That said, unlike “Vesta,” this story is a mystery of sorts.

“Obituary” • (1959) • short story by Isaac Asimov

For obnoxious egomaniac Lancelot, time travel is the means to secure the fame he believes he has been unjustly denied. For his long-suffering unnamed wife, time travel is how she will free herself from a violently abusive husband.

Lance’s wife’s name is left unclear not because Asimov forgot women have names but because she’s the narrator. Unlike every other killer in this book, she declines to provides clues to her real identity. Her methodical cunning would surprise Lance — not his real name — if he were not too dead to be surprised.

This may be an example of the now obscure “there is no legal provision for no-fault divorce” murder mystery genre. Even had no-fault divorce been available, divorcing thin-skinned, entitled Lance might have been too dangerous to risk.

“Star Light” • (1962) • short story by Isaac Asimov

A perfect crime is ruined by an unexpected astronomical event.

See previous comments re outrageous coincidence.

The Key • [Wendell Urth] • (1966) • novelette by Isaac Asimov

To recover a lost alien artifact, Urth must unravel a murdered student’s final clue… which is in the form of a terrible pun.

The murder is ultimately inspired by a philosophical argument over whether Earth would be better off with a slightly smaller population, which can be accomplished over time with conventional methods, or if far more radical population reduction is necessary, in which case, fire up the ovens. It is clear that Asimov is firmly on the side of moderation. I should note that many SF authors of the time seemed to favor radical methods, perhaps because they believed that they would not be the ones pruned. Asimov, being a Jewish writer of Russian origin, was very aware that had events played out even a little differently he would have died in World War II. It may not be a coincidence that Asimov took a dim view of social policies supporting the mass murder of undesirables.

The Key is also unusual for a story of its time in that a character who is unemotional and unempathetic is not praised for his reason and objectivity. He’s shown as having deep-seated personality flaws.

The Billiard Ball • (1967) • novelette by Isaac Asimov

Did the visionary engineer die by misadventure? Or was he murdered by a canny scientist who understood the implications of phenomena that the theory-averse inventor had hand-waved away? Did the scientist use this insight to rid himself of a man he envied?

What bothered me about this story when I read it as a teen was not so much that the anti-gravity device violates the first law of thermodynamics — maybe it’s drawing on a power source not yet understood — but rather, that if the billiard ball that kills the scientist emerges from the field at relativistic speed, it would not have simply zipped through all physical impediments. The result would have appeared akin to a nuclear explosion, as friction swiftly transferred the ball’s prodigious energy to the surrounding air.

1: Fictional murderers in this collection aren’t always first-timers. The killer in “The Singing Bell” was a career criminal whose defining fault was arrogance; he left his victim’s body as a calling card because he was sure there wouldn’t be enough evidence to justify a psychoprobe and he wanted to taunt the authorities.