No shinjū featured in this story

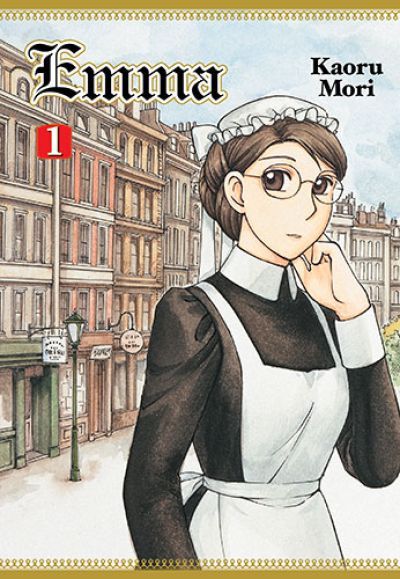

Emma (Emma, volume 1)

By Kaoru Mori

28 Jul, 2015

0 comments

No, not the Jane Austen Emma. Aside from nation of origin and sex, Kaoru Mori’s Emma has almost nothing in common with the more famous Emma; neither class, occupation, personal character, nor personal history.

Emma has no money, no family, no surname, and she owes her position as a maid (and her education and her glasses) to retired governess Mrs. Stowner’s generosity. Despite her lack of prospects, she gets lots of offers, being a comely lass. But Emma has no interest in matrimony

And then one day, Mrs. Stowner’s former student William Jones comes to pay his (extremely belated) respects to his former governess.…

William Jones isn’t aristocratic but his ambitious family, wealthy thanks to generations of effort, can see aristocracy from where they are. The Jones have wealth, they have considerable respectability, and now all they need to enter the upper levels of late Victorian Britain’s stratified society (at least on a provisional basis) is a well-chosen strategic marriage. To date, William has shown little interest in matrimony, much to the irritation of his father and his family.

Both Emma and William suddenly lose their aversion to marriage the moment they clap eyes on each other (which is right after Emma opens a door into William’s face). Chance and duty have led the two to each other. When William leaves Mrs. Stowner’s home, both he and Emma know that they have met their one true love.

Pity the class gulf between them is so large that they almost might be different species, as the Victorians see things. Pity that, even if William is inclined to give in to romance, his relatives are determined that he make a match appropriate for the Jones’ ambitions.

Pity that Emma loves William too much and is far too sensible to tie him to someone like her.

~oOo~

Jeez, this pair can fall in love in a dozen panels (William manages it in at most six) but it takes them 225 pages to get around to their first kiss. And it doesn’t get any faster after that. Various circumstances force Emma out of London, far from William, which cannot help the pacing. Let me just check something … hmmm. There are 52 chapters in the main story and this 500 page book collects 14 of them, so there should be three more volumes to come. I mean, I know they have to end up together at the end (Mori isn’t Ishiguro) but clearly the path between where they begin and where they have to is neither direct nor swift.

Author Mori is enthusiastic about Victorian England without being blind to its faults. Not only is the gulf between rich and poor vast, but lifespans are comparatively short (even setting aside child mortality). As the fate of one character shows, it’s very easy for someone to be healthy one day and dead the next. William has always enjoyed a privileged life, but Emma has not. We see enough of her backstory to get a good feel for how bad things could be for people down at the bottom of the social pyramid. I would say her life before she met Mrs. Stowner was Dickensian, but I don’t think Dickens ever wrote about a character who narrowly escaped being sold to a brothel as a child.

(The author could have tossed in some cholera or TB for giggles but resists the urge.)

There are a couple of minor historical errors. For example, William has a very anachronistic model plane. I gather the author has since acquired an expert on the period as a consultant. And while I am griping, while Mori’s inanimate objects are all distinct from each other, sometimes the English can be hard to tell apart.

Visiting Indian noble Hakim Atawal appears to exist to provide comic relief and romantic encouragement; I don’t think Hakim and Mrs. Stowner ever speak to each other, which is a pity because Mrs. Stowner is also enthusiastically pushing the pair together. The governess and the son of the Maharajah could discuss their shared hobby. Ah well.

Don’t ask me what the deal is with Hakim’s quartet of identical, bored-looking dancing girls. I think the author just likes drawing Indian dancing girls.

It’s nice to be reminded that not everything has to move along at the pace of a Michael Bay movie [1] and that the stakes don’t have to be THE FATE OF THE WORLD to matter to the protagonists. Sometimes the fate of two people is enough.

Emma is available from Yen Press.

1: Would my readers want a review of Yokohama Kaidashi Kikou? It’s about a tea house after the end of the world as we know it and is far more leisurely in its pacing than Emma.