Noble Lustre in Your Eyes

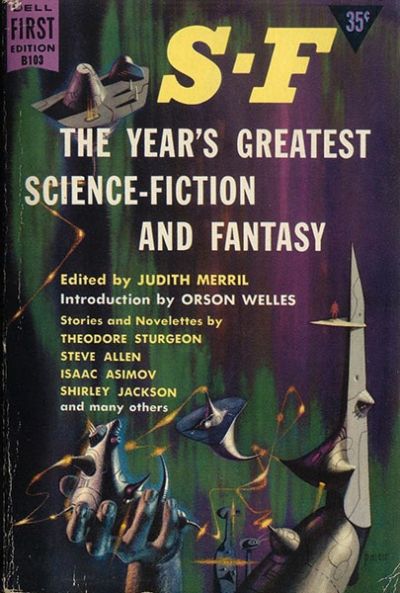

S‑F: The Year’s Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy (The Year’s Best S‑F, volume 1)

Edited by Judith Merril

7 Mar, 2023

Judith Merril’s The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy

1956’s S-F: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy was the first of twelve volumes in Judith Merril’s The Year’s Best SF anthology series.

Merril does not state in her title the year for which this is the best SFF. It seems to be traditional for debut volumes of Best SF annual anthologies to omit any indication of which year is covered and Merril helped pioneer that tradition. I would guess that Merril and her publishers expected the shelf life of the anthology to be limited enough that the exact year would not be an issue.

Speaking of publishers: the hardcover was issued by Gnome Press, a company of some significance and great notoriety in science fiction. Founded by David Kyle and Martin Greenberg (but not the Martin H. Greenberg of whom you’re most likely to have heard), helmed by Greenberg, Gnome was a pioneer in the field of speculative fiction hardcovers and a stalwart protector of writers from the royalties they were owed. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a Gnome Press book in the wild, probably because they folded around the time I was born.

By my count, this volume includes three essays (two by a woman—the same woman—and one by a man) and eighteen short stories (fourteen by men, three by women, and one a collaboration between a man and a woman). Ah, well. At least women got more representation in this volume than they did from Bleiler and Dikty. As well, while the text uses ‘man’ as the default for human, Merril acknowledges in her preface that women authors do exist, something that is not always a given in SF anthologies of this vintage. Merril may have been tipped off to the existence of women authors by being one herself.

This is, alas, a rather uneven volume. To make matters worse, Merril appears to have positioned the weakest stories at the beginning. The good news is, if one perseveres, the stories get better. The bad news is that many readers may want to give up early. Perhaps context matters. Maybe these stories, even the disappointing ones, really were the best stories 1955 had to offer.

However, the volume is rewarding for a number of reasons. For one thing, this may be the only such work I’ve ever read that features an introduction by Orson Welles. I am certain that this volume contains the only Steve Allen SF story I’ve ever encountered. A number of the stories (“Pottage,” “Nobody Bothers Gus,” “The Last Day of Summer,” “One Ordinary Day with Peanuts”) are noteworthy in a positive sense, as are the essays “The Year's S-F,” “Summation,” and “Honorable Mentions.”

Most noteworthy: not the stories themselves, but the anthology’s structure. It features commentary on each author, as well as a summation of the state of science fiction in the year 1955. I’ve seen this approach before: Gardner Dozois used it in his Best SF annuals, as did Lester del Rey before him. Since Dozois assumed the helm of the del Rey series before launching his own, I wondered if Dozois was inspired by del Rey. Now I wonder if del Rey and Dozois borrowed from Merril. Merril’s contemporaries presenting their own Best SFF anthologies do not appear to have presented their material in this manner, so it cannot have been the accepted presentation.

It is a sign of the times that Merril’s sources break down as they do:

Astounding - 3

The Blue Book Magazine- 1

Fantastic - 1

Galaxy - 3

Good Housekeeping - 1

If - 1

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction - 6

No Boundaries - 1

Science Fantasy - 1

I am certain that had this volume been assembled in 1946 instead of 1956, the table of contents would have been dominated by stories drawn from Astounding. By the mid-1950s, however, the bloom had very much gone off Astounding’s rose. Its commanding position had been taken over by the more innovative Galaxyand The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (F&SF). Oddly, Merril seems a little dismissive of F&SF despite drawing so heavily on it.

Each story is accompanied by a brief note about the story’s author.

“Introduction” (S-F: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy) • (1956) • essay by Orson Welles

A glowing introduction from the famous film maker. Welles thought the SFF novels of the period were dire, but he was fond of short SFF.

“Preface” (S-F: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy)• (1956) • essay by Judith Merril

A brief lead-in, presenting Merril’s views on quality SFF.

The Stutterer • (1955) • novelette by R. R. Merliss

An indestructible android sneaks his way to Earth in a desperate bid to save his immortal kin from a fate worse than death.

This story was, to put it mildly, terrible.

“The Golem” • (1955) • short story by Avram Davidson

An irate android, convinced that conflict between human and android is inevitable, is undone by a wacky Jewish couple.

“Junior” • (1956) • short story by Robert Abernathy

Generational conflict, under the sea: Junior refuses to settle down like a proper person would.

The joke being that sea creatures have the same sort of conflicts the Silent and Boomer generations were having, if played out a bit differently.

“The Cave of Night” • [Station in Space Universe] • (1955) • short story by James E. Gunn

America unites to save an astronaut stranded in space. Except there is more to the story than first appears.

This is a cousin to “they faked the Moon landing” fables, not to mention “if you fake it well enough, it will come true.” Oddly, this wasn’t published in Astounding but in Galaxy.

“The Hoofer” • (1955) • short story by Walter M. Miller, Jr.

A drunken wreck of a spaceman would love to return to Earth and his family, but his personal flaws ensure he will never be able to do so.

The kindest thing I can say about Miller’s view of how space work might function is “implausible.” It’s not a great Miller story, which may explain why editors after Merril didn’t collect it until after it entered the public domain and they didn’t have to pay for it.

Bulkhead • (1955) • novelette by Theodore Sturgeon

A space cadet learns after the fact the lengths to which his superiors will go to protect cadets’ mental health in space.

Sturgeon seems to believe that there had never before been jobs where people worked in isolation.

Sense from Thought Divide • [Ralph Kennedy] • (1955) • novelette by Mark Clifton

A psionics researcher struggles to convince a scam artist that his powers are real.

This story was awful; it was also long. Cue lamentations that I cannot just skip past the dire stuff when reading for review. I have no idea what people saw in Clifton’s work.

Pottage • [The People] • (1955) • novelette by Zenna Henderson

Alien refugees hidden on Earth encounter a lost community of their kin. Can conflict be avoided?

This is a Henderson story, so it is almost certain things will work out in the end. The road getting there will be rocky.

“Nobody Bothers Gus” • [Gus] • (1955) • short story by Algis Budrys

A day in the life of a poor, pitiful superman.

This particular breed of miserable superman combines ultra competence with psychic camouflage that precludes ever getting credit. Bonus: no pitchfork-waving mobs angry about the appearance of the Next Race. Minus: he’s very, very lonely and unlikely to have kids. This belongs to a small but memorable subgenre focusing on how much it sucks to be super.

“The Last Day of Summer” • (1955) • short story by E. C. Tubb

Aware he has aged past the limits of rejuvenation technology, an old man does his best to enjoy his final day of life.

Tubb’s prose is never more than mediocre, which in the case of this story is a bit of a pity.

“One Ordinary Day, with Peanuts” • (1955) • short story by Shirley Jackson

A husband and his wife pursue similar and yet very different hobbies.

“The Ethicators” • (1955) • short story by Willard Marsh

Well-meaning aliens seed barbaric Earth with something they consider the very basis of true civilization.

“Birds Can't Count” • (1955) • short story by Mildred Clingerman

Intrigued by her discovery of an other-dimensional voyeur, a woman is extremely put out when she discovers the voyeur’s true target.

Cat pictures.

Of Missing Persons • (1955) • short story by Jack Finney

An unhappy man is offered paradise … with conditions.

Those who do not learn from Orpheus are doomed to recapitulate his fate.

“Dreaming Is a Private Thing” • (1955) • short story by Isaac Asimov

A dream merchant struggles with the challenges of the ever-evolving field of entertainment, from the appearance of pornography to the rise of a mass market in dreams.

I would have sworn I’d never read this, but it is in Earth is Room Enough, which I own.

“The Country of the Kind” • (1956) • short story by Damon Knight

A social pariah, shunned for good reason, searches in vain for similarly broken individuals.

“The Public Hating” • (1955) • short story by Steve Allen

Having harnessed psi powers, America uses them to enact that most American of rituals, the death penalty.

The … well, an interesting twist is that the starting premise is that individual humans have almost no psi power. They have a sufficiency if they work in concert. Turns out that it is pretty easy to rile up crowds against public enemies. It’s not a coincidence this is a McCarthy-era story.

Home There's No Returning • (1955) • novelette by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore

War has grown too complex for Man to master. Will robots do any better?

In short, no. Where’s Henry Kuttner’s Gallegher when you need him? Not that the Proud Robot would have been much use in war….

“The Year's S-F, Summation and Honorable Mentions” (S-F: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy) • essay by Judith Merril

An enthralling summation of SFF’s history, in particular recent history. Also trenchant comments on the various SFF publishers. Magazines are discussed in detail (oddly, F&SF is discussed in more dismissive terms than one would expect given how much of the book is drawn from that magazine’s pages). This review of the field would have been of great value to me if this were 1956 and not 2023.

Interestingly, Merril’s view of SFF is of a field struggling to survive publishing disasters. I thought the big SFF collapse was a bit later; is publishing always in a state of recent calamity and impending doom?