Not Exactly Queen of the Undead

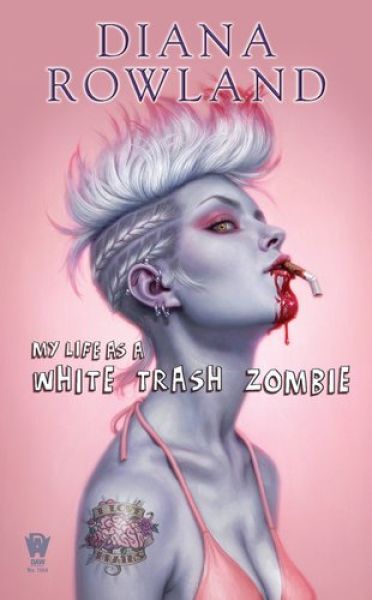

My Life as a White Trash Zombie (White Trash Zombie, volume 1)

By Diana Rowland

30 Jun, 2015

0 comments

2011’s My Life as a White Trash Zombie begins with a scene with which readers will be familiar from scores of movies and books: protagonist Angel Crawford wakes in a hospital bed with no idea how she got there. The news that she barely survived an OD is believable given her drug habit. What is inexplicable, thanks to the giant hole in Angel’s memory, is why she was found wandering naked on a back road miles from anywhere. More mysteries: is her appearance on that back road related to a murder that had taken place nearby? Which mysterious benefactor left her a supply of unfamiliar tasting but nummy slushies, along with a letter explaining how to conduct herself over the next month in order to avoid jail and inevitable death?

Angel’s amnesia erased hours from her life [1] but at least (unlike many characters in her position) she knows who she is. What she doesn’t know is what she is.

Her mysterious benefactor arranged a job for Angel, as a van driver at Saint Edwards Parish Coroner’s Office, a job she has to keep for at least a month. Angel has had a long sequence of minimum wage jobs, all lost thanks to her pill-popping, self-sabotaging ways. However, jail terrifies her (for various good reasons) … and all it would take to land her there is a call to her probation officer.

Angel discovers that the job description for morgue driver is broader than the name might suggest; she is expected to assist in the morgue within the limits of her skills. Although she has a track record of extreme squeamishness (it was a high school biology lab dissection gone wrong that ended with her storming away from high school forever), oddly enough, Angel finds that she has no problem handling the bodies in the morgue. Not only that — it turns out that if she applies herself, she’s acceptably competent. Until now, she had been marked as a loser by class and family background. She had never been expected or encouraged to excel, not even by herself.

Angel gradually comes to terms with a new life that isn’t a series of lost jobs, pill-popping, casual sex with her loser boyfriend, and eventual death (accident, murder, or suicide — all were equally likely). But she cannot ignore vexing questions about the recent past. What happened to her, that night she was found on Sweet Bayou Road? Why do her fragmentary memories of the night suggest horrific violence (even though she woke in the hospital without a mark on her)? Who is her mysterious benefactor? What’s in those … slushies? Who is leaving decapitated bodies all over the parish?

And why do brains suddenly smell so very, very tasty?

~oOo~

I decided to review this because I had read the second the book in the series and while I am not some kind of obsessive [Editor’s note: oh no, clearly not!] , reading the second book in a series and not the first one, despite the first one being trivially available, would have made me feel as if there were an annoyed bee bouncing around in my skull.

“Protagonist wakes up in a hospital having either slept through important events or forgotten them” is a pretty common opener. The protagonist generally gets handed a stack of perplexing clues to be unraveled, once they have left the hospital and discovered just how their world has gone to hell. Variations on theme: 1) the reader knows what’s going on before the protagonist does and 2) the reader figures it out along with the protagonist. Both variations are so useful for writers that they get invented independently over and over. In this case, however, I don’t think it’s reinvention. I suspect Rowland is paying deliberate homage to works like 28 Days Later and The Walking Dead.

Rather like Angel’s mysterious benefactor, Rowland lets Angel figure things out all by herself. Angel is given sufficient supplies to get her through the first month and plonked into an environment where she can gradually grok that she’s now a brain-eating zombie (benefits and limitations included). I understand why that’s the most interesting decision from a narrative point of view but … given the need to keep the existence of zombies secret, given the unfortunate tendency of zombies to become ravening monsters when they get hungry enough, I don’t know why this decision made any sense to her benefactor.

An interesting math problem: take the death rate of the region and the rate at which zombies need to eat. Work out the maximum number of zombies a given region can support, assuming that all the recently dead brains are handed out to drooling zombies as efficiently as possible [2]. For example, Waterloo Region should have something along the lines of 3600 deaths a year [3]; if a zombie needs one brain every other day [4], then 3600 brains is sufficient to keep 20 zombies fed and happy. Of course in practice supply inefficiencies would reduce that number. I am not 100% sure Rowland ever did such a calculation: Saint Edwards Parish isn’t crawling with zombies, but there do seem to be more than can be supported, given reasonable assumptions about brain supply.

Your average urban fantasy/paranormal romance protagonist, on learning that they have Very Special Powers (either because they had an Origin or thanks to good breeding), generally chucks every post-Enlightenment value to embrace social systems so hilariously stratified, displaying such callous disregard for the despicable mundanes, that even Louis XV would be taken a bit aback. Superheroes at least feign concern for Collaterally Damaged Americans as the masked marauders crash through cities; UF/PR protagonists generally cannot be bothered. Civic responsibility and adherence to any political tradition later than CE 1700 would get in the way of being sparkly.

Angel is one of a very, very few exceptions to this pattern. Her new Very Special Powers (and the fact that someone in a position of power decided she was worth giving her a hand up) give her a chance to work her way up to the level of privilege enjoyed by most middle class Americans. She’s not the Queen of Suburban Vampires and she’s not juggling a dozen Faerie lovers, each more handsome, powerful, and ruffled-shirt-ish than the last. Angel’s landed a decently paid job for the first time in her life. She’s not going to be handed a kingdom, but if she plays her cards right, she might get her own apartment.

How much of Angel’s reinvention of herself is because she finally has the chance to develop potentials she had all along and how much of it is because (small spoiler here) the parasite that causes zombie-ism is moderating her behavior to improve its own changes of survival? I think it’s a bit of both. If Angel had actually been the worthless, hopelessly dim fuck-up she thought she was, she wouldn’t be able to capitalize on the opportunity that she is handed. Even if many of the changes are due to a parasite yanking her strings, humans are already a collection of tropisms, habits, and unconscious decision-making processes (heavily influenced by the gut biome), topped with a patina of consciousness kidding itself that it’s in charge.

Out of curiosity I searched my finished review folder to see if I’d read any Rowland before last week’s Even White Trash Zombies Get the Blues. Hmm … I see that I reviewed 2009’s Mark of the Demon, which I didn’t hate and didn’t love. I enjoyed My Life as a White Trash Zombie, but not as much as I enjoyed Even White Trash Zombies Get the Blues. That’s good, because I read Life and Blues in the wrong order; Rowland seems to be getting better over time.

My Life as a White Trash Zombie is available from DAW.

1: And is completely explicable given that she has flunitrazepam in her system. Nobody at the hospital seems to pick up on that; I would say that’s partly due to Mysterious Benefactor suppressing the report (she was also positive for other, parole-violating, drugs, and her probation will be yanked if anyone official finds out) and partly due to the fact that nobody at the hospital cares that some white trash girl with a bad dye job got roofied.

2: In other, more advanced, nations, treatment of partially deceased syndrome would probably be something that a single payer health care system would handle efficiently (at least after the first few whoopsies involving a hungee hungee zombie in a waiting room). This book is set in the US, so there’s a free market solution. Control of the brain market is handled by a few well-placed gatekeepers. In this specific case, the system doesn’t seem to work anywhere nearly as badly as you might expect. Two factors might explain this: the gatekeepers do not want large numbers of zombies to go hungry (with dire consequences) and the insurance companies (even more predatory than zombies) are completely locked out of the process.

A note to authors reading this: as far as I know, while I know of one “zombies meet the NHS” series, I don’t know of any zombie novels where the undead have to navigate an American insurance company’s barrier of forms and phone trees.

3: ~3600 a year works out to about ten a day. Waterloo Country is fairly efficient at processing dead bodies, so the equilibrium supply of fresh(ish) corpses is maybe forty or fifty — at this juncture I would like to thank local funeral homes for cheerfully fielding some odd sounding questions, including “I don’t really want to explain why I am asking this but how would you handle a sudden influx of, say, 1500 dead bodies?”[5] — scattered across the local morgues and funeral homes for the most part. I think the way an actual zombie apocalypse would work is that a few zombies here and there would wake to find themselves trapped in secured drawers and coffins. There would be lot of frustrated knocking and clawing and not much else happening.

(Not that your classic zombie apocalypse has much to do with this book. Rowland isn’t writing about obligately ravenous zombies with no capacity for self-control, at least not in My Life as a White Trash Zombie.)

4: The need for brains can be reduced by limiting physical activity; many zombies spend as much time as they can parked on the couch in front of the TV. The next book reveals older zombies need fewer brains, but I do think that this calculation gives a good idea of the overall brain-supply situation.

5: It turns out at least some of the people in the local funeral home community (and probably elsewhere) have spent some time thinking about how they’d handle unlikely but possible scenarios. Whole Canadian towns have been obliterated by wildfire, washed away when a dam upstream collapsed, or crushed when ore mountains fell over. None of those are likely in Waterloo County, but there are enough Possible MegaBads that it’s worth taking a few minutes to work out contingency plans.

The bottleneck turns out to be available backhoes. Coffins can be had in quantity. Processing could be sped up considerably if it were necessary. There are lots of gravesites available. If there were huge numbers of casualties, they’d use heavy earth movers to fill mass graves. However, 1500 bodies wouldn’t justify that. That number is too small for mass graves and too big for business as usual.