On My Way To Mars

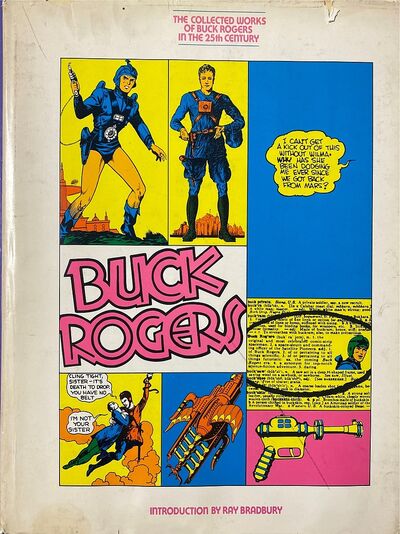

The Collected Works of Buck Rogers in the 25th Century

By Philip Francis Nowlan & Dick CalkinsEdited by Robert C. Dille

13 Apr, 2025

Robert C. Dille’s 1969 The Collected Works of Buck Rogers in the 25th Century is a collection of Buck Rogers strips from the 1920s to the 1940s. Early story arcs were written by Phil Nowland and illustrated by Dick Calkins. The last two arcs are by Calkins alone.

Trapped by a mine collapse, 20th century American Buck Rogers is surely doomed, in this, the first panel of what would be a long-running series.

When Buck wakes up, he finds that the USA has been delenda1.

Buck wakes from slumber and discovers that his path to the surface is now open. He finds himself in a world transformed. A woman — Wilma Deering — falls from the sky, oddly unharmed. While she rewards Buck’s efforts to protect her from the men chasing her by holding Buck at rocket-pistol point, once she is convinced Buck is a white hat, she befriends Buck. More importantly, Wilma explains what is going on.

It is the 25th century. America was long ago conquered and occupied by the Mongols. The Mongols being content to remain in their cities, the surviving Americans were able to form freedom-fighting “orgs.” The orgs have been unable to liberate America despite centuries of struggle.

Of course, until now, the orgs have never had someone like Buck, whose talent for running headlong into danger is matched only by his ability to survive doing so. Whether engaged in pointless romantic squabbles with Wilma or conducting daring raids into Mongols territory, Rogers is the archaic American that the rebels need.

However, even if Rogers can somehow drive the Mongols from North America, can even he protect Earth from the Tiger Men of Mars, perfidious Atlanteans, or the Monkey Men of Planet X?

~oOo~

Delicate readers should be aware that casual violence and even more casual death abounds, up to and including ecocide after the good guys drop a moon on Mars. It was the 1930s! Nobody knew genocide was bad!

Not that the strip always resorts to violence. Buck can, when needed, deliver irresistible oratory when he needs to.

In defense of Calkin’s regrettable visual depiction of Asian people2, conditions in 1929 reflected decades of relentless efforts to ethnically cleanse the US. Who is to say if a particular artist would have ever actually seen Chinese people or if, having seen them, would not immediately collapse with a fatal brain aneurysm from the shock? It is important when assessing American works of this era to set the bar very low.

Mitigating the art somewhat, Nowlan clearly wasn’t happy with his novel’s solution regarding Wilma’s genocidal racism3. Nowlan’s Mongols are…. nuanced is too strong… more complex than one would expect from the initial strips. The North American Mongols have factions, some of whom are willing to work with the Americans.

In fact, in a twist I had completely forgotten in the half-century since I first read this tome, it turns out that the entire invasion and conquest was a scheme cooked up by ambitious functionaries. When Buck and company confront the immortal Mongol emperor in far-off Asia, the emperor is astonished and aghast to discover that the Americans did not invite his empire to assume governance of the US. His subordinates have been lying to him about North America the whole time it has been occupied.

Another detail long forgotten: while the US was easily conquered and occupied, Canada remained free territory.

This seems perfectly reasonable.

Characterization is somewhat inconsistent… or perhaps I should say plot driven: if Wilma needs to be an action girl to keep the plot moving, she is. If she needs to be kidnapped, she is easily overpowered. This flexible characterization applies to most of the characters.

Towards the end of the collection, Calkins turns his dubious talents to writing as well as art. This permits him to express his displeasure at the Japanese, who had only recently attacked Pearl Harbor. The result is memorably racist, even by the standards of a strip that started off being about the Yellow Peril.

Speaking of dubious talents, while I understand why Dille produced the collection — the Dille family is relentless in its efforts to monetize Buck Rogers4—I am not sure what criteria guided Dille in his selection of strips. Why are only parts of some arcs included? Why, a generation after WWII, end the collection with the Monkey Men arc? Why include that arc at all?

The book itself is unwieldily large, while the strips are printed in a small format that is difficult to read. Hmmm. I don’t remember having issues reading this copy the first time I took it out of Dana Porter Library half a century ago5. Presumably the art shrank with age.

This collection isn’t the best introduction to Buck Rogers, so it’s not a terrible tragedy that the book is out of print. However, if you are Buck Rogers curious, an extensive archive may be found here.

1: USA delenda est!

2: As far as I can see, there were no Africans or African diaspora persons in the strip. Given how almost every other group, from Mongols to cowboys to Native Americans, are broad stereotypes, this is probably for the best.

3: Which was to declare that with the single exception of the Mongols, Wilma was terribly open-minded about people of other races, from Europe to Africa, and also it turned out that the Mongols weren’t actually human, so it was OK if Wilma amused herself by tossing the occasional Mongol infant into a wood-chipper.

4: Which is why TSR (more famous for Dungeons and Dragons) kept producing Buck Rogers games while managed by Lorraine Williams. Williams was the granddaughter of Dille Family Trust founder John F. Dille. The Trust owned Buck Rogers; the potential synergy between the Buck Rogers IP and a gaming community for whom Williams had boundless contempt was obvious. As it turned out, though, the synergy remained potential.

5: I also did not remember that this copy is autographed by the editor. I will point that out to the library.