Parents Who Love Their Kids to Pieces

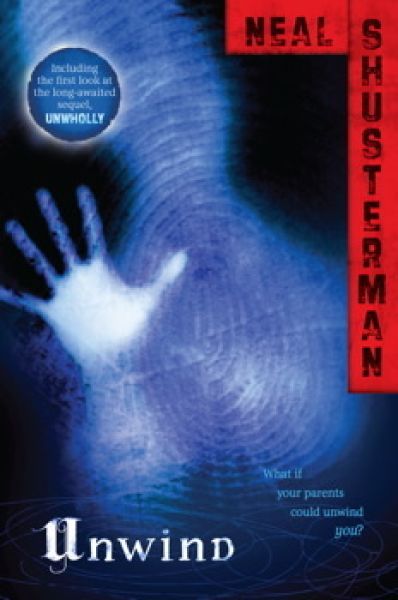

Unwind (Unwind Dystology, volume 1)

By Neal Shusterman

17 Oct, 2015

0 comments

Neal Shusterman has been publishing for a quarter century, but 2007’s Unwind is the first novel of his I recall having read. I wish I liked it more.…

The Second Civil War was fought over reproductive rights. None of the factions involved were able to win a complete victory. The compromise that emerged from peace talks was as counter-intuitive as it was inhumane. While the US legal system now considers life to begin at conception, from ages thirteen to eighteen, parents can opt to consign unsatisfactory children to the organ banks, a process called unwinding. As long as 99% of the teen is used for organ donations, they have not technically died, only become more dispersed. Everyone is happy!

Except for the teens who are slated to be unwound. Eh, teenagers, always complaining.

Connor’s offense is that he is a habitual disciplinary challenge, unable to control his temper. Unwind! Risa, on the other hand, is perfectly well-behaved, but her marks, while not awful, haven’t met the exemplary standards expected of a ward of the state. Unwind! Lev is a perfect angel but his family’s religious principles require them to sacrifice one child for the greater good. Unwind for him too!

Most children consigned to provide organs for their betters are snapped up by the system too efficiently to allow of escape. No system is perfect, however, and all three teens manage to escape, at least for the moment. An unlikely set of circumstances forces the trio to unite as they go on the run from the Juvey-cops.

The trio faces some serious challenges. The Juvey-cops in charge of recovering AWOL Unwinds have numbers, organization, and legitimacy on their side. Most Americans seem enthusiastic about the Unwind system or at least not unhappy enough to do anything about it. Plus Lev isn’t so much a runaway so much as an (unwitting) hostage to Connor and Risa. A brainwashed willing tithe, once Lev sees a chance to betray his two companions, he is going to take it.

A minority of Americans are willing to provide AWOL Unwinds with temporary refuges. The so-called Fatigues go even farther, shipping vast numbers of AWOLs to a secret facility far from official eyes. That may not be entirely altruistic; a workforce that can’t leave without risking dismemberment is a loyal workforce.

~oOo~

Authors like to talk about how books aren’t fungible, but, to be honest, the concept of genres seems to rely on the idea that to some degree books are interchangeable: if you like one $genre book, you might also like another $genre book. Some genres have larger and looser constellations of conventions than others, however, and few genres are as narrow and constrained as the modern Young Adult Dystopia.

There’s no reason why an art form with a very specific set of conventions cannot produce memorableworks of art. Some verse forms, such as the sestina, are quite constrained. One can confidently predict the form of a sestina — but not its quality. Some are divine, some are doggerel. This holds true for Young Adult Dystopia; knowing a book falls into that genre tells the potential reader a lot about the conventions they are likely to encounter … but nothing about the quality.

I regret to report that Unwind falls short of the divine.

It is true that extraordinarily contrived societies are an essential part of Young Adult Dystopia1. Teenagers forced to cope with a cruel, arbitrary world make interesting, sympathetic protagonists. But the contrived society imagined for this book is just too damn contrived to be believed. Ever since the War of 1812 and the rise of the Family Compact that followed that war, Canadians have been encouraged to believe the worst of Americans and their governments. I grew up in Canada, I went to Canadian schools, and even I could not suspend my disbelief in Shusterman’s society long enough to enjoy the book. Even though convincing a Canadian reader that an American society is despicable is such a low bar, it requires a trench.

Now, I could very easily believe a US where people used each other’s kids for spare parts, particularly if particular racial and socioeconomic classes were targeted for dismemberment. I could believe in a US where a few parents toss disappointing children into the organ banks; the US has millions of parents, so some of them are bound to be very very awful. But people doing this to their own kids, en masse? That is an unbelievably inhumane. Nor can I believe that anyone would have come up with this nutso system in the first place, much less managed to have it accepted as a compromise. And yes, I know Shusterman explains how it happened, but I still don’t believe it.

Not to mention that the law requires that 99+% of each Unwind be used for transplants, which is impossible. Just how many left ear transplants are performed each year?

I cannot figure out if this is a snowglobe story, in which the setting only makes sense if you assume there is some impenetrable barrier preventing the characters from fleeing the rotten society. Common snowglobe tropes: all other humans are dead, or, the evil society controls the whole planet. There is no escape, because there is no outside. Well, there is some evidence this is a snowglobe novel: as far as I recall the kids don’t talk about escaping to Canada or Mexico. On the other hand, it’s possible that Canada and Mexico have been conquered by the partsmongers. On the gripping hand, schools may have stopped teaching geography and the kids may never have heard of Mexico or Canada.

And yet … 18th and 19th century American slaves knew about Canada, even though their owners were pretty dedicated to keeping the slaves ignorant. Even though Dixie didn’t have the internet. Slaves figured it out; potential Unwinds would do so as well. They would be very motivated autodidacts as far as escape strategies were concerned.

The cynical explanation? The target market for this book is contemporary American teens, who may not find “escaped to Canada” an appealing resolution, not out of any dislike of Canada, but out of disinterest in Canada. You may be familiar with this sort of American self-absorption from American WWII movies, in which Americans do the derring-do and the Allies are mere set dressing.

If I had to go with one word to describe this novel, I would select “contrived.” For example, there’s a fairly disquieting scene where we find out exactly how the unwinding process works. It’s slow, starts at the feet, and the donor is conscious throughout. It’s a horrifying scene but also one that does not seem plausible 2, unless it was contrived to disgust and outrage the reader. (Though in my darker moments, I suspected that the author was targeting readers who like horrifying surgical procedures. Perhaps readers who like movies such as Tetsuo.)

It is not all bad:

- The prose is functional enough.

- The characters don’t have much depth, but they are not all cut from the same mould. By using one antagonist as the sacrificial lamb in the how unwind works scene, Shusterman transforms that character into a sympathetic figure.

- The plot is a familiar one but I enjoyed previous iterations of this particular plot [3], so that is not necessarily a mark against the book.

- The lesson that negotiations can end in highly counter-intuitive compromises is, I guess, a worthwhile one — even if I didn’t find this particular example believable.

All books are deliberate creations; it’s not as if the words spontaneously swirl together into a coherent story. I acknowledge that, but I like my Suspension of Disbelief. I want to remain immersed in the story and its world, rather than being perpetually aware of the book as an artefact. I would rather wonder about the motivations of the characters than the motivations of the author. While reading this book, I found myself interrogating this text from the wrong perspective. Not my cup of tea.

Unwind is available from Simon & Schuster.

1: I am sad to say that science fiction seems to prefer contrived dystopias to sensible solutions. SF novels in which overpopulation figures, for example, have suggested such schemes as keeping people as brains in boxes to minimize their power and nutrient consumption, or forcing people to sleep six days out of seven, or installing secret, undocumented fertility inhibitors in women.

You may ask “is there any SF suggesting that we educate women, given that one reliable method of reducing the total fertility rate is women’s education?” To which I respond with hollow laughter. If it’s not cruel, draconian, and implausible, it’s not really an SFnal solution

2: Speaking of things that do not seem plausible, the author sprinkles little newsy factoids though the text to lend verisimilitude to an otherwise unconvincing narrative. Example: babies harvested for stem cells in the Ukraine:

No follow-up to that sensational story, which suggests that it might not be … entirely true. The charitable interpretation is that Shusterman fell prey to confirmation bias: it sounded plausible to him so he didn’t double check.

3. In short: bad government targets teen protagonist, who is forced to go on the run and meets unexpected allies. There’s generally an unexpected setback around this point, after which we gallop onwards to the implausible victory! Unless it’s a series, in which case there will be more unexpected setbacks and it might take a few volumes to get to the victory.