Quit Hollering at Me

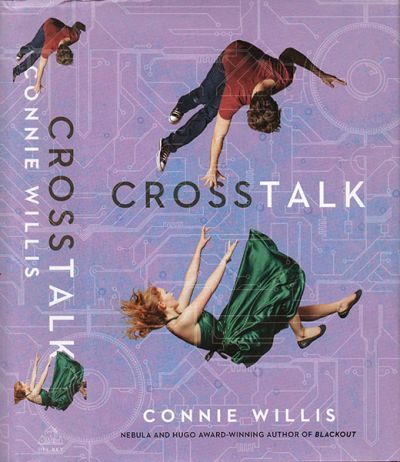

Crosstalk

By Connie Willis

24 Jan, 2017

0 comments

Connie Willis’ 2016 Crosstalk is a standalone near-future SF novel. I regret to inform my readers that this review may not be as enjoyably vitriolic as previous Willis reviews. (I may revisit that decision once Crosstalk gets its inevitable, inexplicable Hugo nomination.) As Willis novels go, I didn’t hate it all that much.

In the exciting world of Tomorrow CE, couples are not limited to intrusive social media and ever-present electronic communications. Now there’s the option of the EED, a device that creates an empathic link between lovebirds. Or at least, it’s supposed to.

Pressured into submitting to elective brain surgery by her loving fiancé Trent, Briddey Flannigan gets an EED. Alas! there is no sign of the empathic link that should have formed between Briddey and Trent. What Briddey got was…

Telepathy.

Not as nice as one might think. Everyone has thoughts one would find embarrassing if broadcast. But Briddey finds herself in a predicament even more bizarre; she is not connected to Trent, but to co-worker C. B. Schwartz. C. B. is by no means a monster, but he is also not someone she wants listening to her every thought. Or broadcasting his thoughts into her mind.

The telepathy doesn’t stop with C. B. Her telepathic reach grows with each passing hour, filling her head with increasing mental cacophony. C. B. is of course aware of her discomfort and can offer her a few coping mechanisms.

The fact C.B. seems quite familiar with the ins and outs of telepathy raises some uncomfortable questions.

Trent is upset that he has no empathic link with Briddey. What will he do if he finds out about the telepathy? Accuse her of telepathic adultery? Decide Briddey is insane? Turn her over to the scientists as an experimental subject? Or will the ambitious Trent figure out some way to monetize telepathy?

~oOo~

This book has most of the characteristic Willis tropes: unlikeable characters1, idiot plots, contrived communications issues, and a tendency to dismiss as half-witted anyone who behaves in a way of which the author disapproves. While these are negatives for me, Willis fans apparently love this stuff. Chacun à son goût, right? I suspected I would not like this book, but I read it anyway. Nobody even paid me to read it. I have only myself to blame.

In a spirit of fairness, then, let’s talk about the ways in which this book wasn’t as terrible as it could have been.

Wait! Let’s start with a plot point that shows why near-future SF is such a dangerous genre in which to work. Events have a way of evolving in ways that make short-term SF outdated overnight. Venus’ true nature was revealed midway through the serialization of Podkayne of Mars, which used a pre-Mariner‑2 Venus. The fact that Mercury is not locked into a one to one spin-orbit resonance was discovered in the interval between Niven writing “The Coldest Place” (which depended on Mercury having one face in eternal daylight) and that story’s publication. Willis had the misfortune to pick as an example of a high-profile romantic couple a pair of celebrities who timed their divorce to coincide with the publication of this book. It happens.

I don’t have any issue with the subplot about the niece and the helicopter mom. I don’t think you should need a specific communication-blocking app to deal with such moms. But it’s useful to be reminded that one can just ignore communication when it proves disruptive. (Maybe not teenagers, whose lives become less free with each passing year, but adults can.). That’s why I don’t look at email after midnight (lest I become too agitated to sleep). That’s why I now know how to block certain people on Facebook and Twitter. Just because 24×7 communication exists is no reason to drown in it.

Having trudged through all 1168 pages of a previous Willis novel (Blackout/All Clear) I was thrilled to find that Crosstalk is a complete novel in just 498 pages! That’s even shorter than 2001’s Passage (nearly 600 or 700 interminable pages, depending on the edition). Since I actually like Willis’ short fiction, or some of it, shorter is better for me.

It is not uncommon for near-future SF novels to be essentially stock detective novels, ones in which the central McGuffin could be replaced by a sealed manila envelope without affecting the plot overmuch. Crosstalk is legitimately SF: you cannot remove the SFnal elements of the story without destroying the plot. Admittedly, some plot elements — such as the premise that the Irish are sufficiently genetically distinct from the rest of humanity that only persons of Irish descent have a particular trait2—are stupid. However, works that are canonically SF have used even dafter ideas to generate stories3. The important thing is, Crosstalk really is SF.

Crosstalk is available here.

1: Most of the negative commentary I’ve read focuses on the protagonist. In my case, I found the manipulative C. B. even more off-putting. And Willis lets him get away with pushing Briddey around! As does Briddey. Someone is not wearing her pussy hat.

2: Some of you may be familiar with thrilling tales of super-powered psionic redheads. You may be rolling your eyes at the idea of yet another novel about Celtic Ubermenschen (and frauen and non-binary-en). Rest assured that the genetic trait that distinguishes the Irish is deleterious. All other human genetic populations have eliminated or at least mitigated it. The Irish are not demi-gods in this story, but genetic cripples. That’s better, right?

3: I hate to have to tell you this (it’s like denying Santa and the Easter Bunny) but there’s no convincing evidence that any of the dodges SF writers use to get around the light-speed limit have any basis in reality.