When The World Is Our Rotisserie

Days of March

By John Brunner

24 Sep, 2024

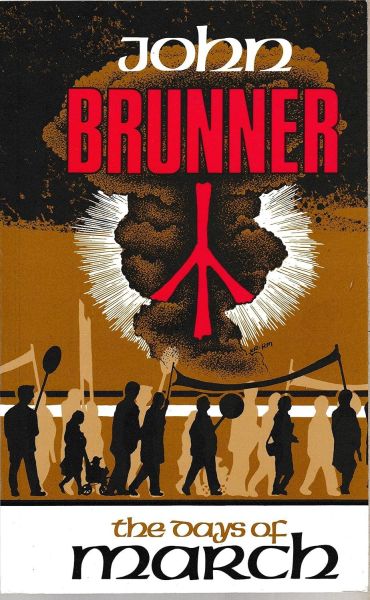

John Brunner’s 1988 Days of March is a stand-alone mainstream novel.

There are many goals that Micky Daws would like to accomplish in 1962. However, to accomplish them Micky needs not to get incinerated in a nuclear exchange. Thus, Micky’s dedication to Liberty, an organization campaigning for nuclear disarmament.

Luckily for Micky and his allies, his employment allows ample free time to devote to the political campaign. Micky being easily distracted; time is a vital resource. Saving the world is important but so are music, parties, and chasing women.

It’s not enough to want to save the world. There are mundane logistical issues to manage. Someone has to show up for debates, answer the phones, print the posters, distribute the posters, and all the other petty tasks that are part of a political campaign. Micky, whatever his faults, is a willing, dependable worker.

Although Her Majesty’s Government takes an oddly hands-off view of the organization, there are other challenges. An unlovable chum is dispatched on a minor errand. The goal is free the office from the fellow’s grating presence. The actual result is a horrific, fatal traffic accident for which Micky feels responsible.

Disarmament is just one of many reforms suggested by the UK’s left wing. Liberty is considered left-wing, thus has an abundance of enemies on the right. Some of Liberty’s enemies want to break heads. Others keep an eye out for opportunities for more meaningful sabotage.

Liberty’s greatest foes might be one of its own allies. Bruises heal, trashed offices can be tidied up, but it’s best for political activists not to be found in possession of expensive stolen goods… as Liberty finds out, the hard way.

~oOo~

This review is brought to you by the miracle of academic libraries and interlibrary loan. I’ve never seen a copy of this mainstream novel in the wild. No doubt because Days of March is mainstream, the SF community does not appear to have taken note of the work at the time. In fact, if ISFDB is a guide, there were just two reviews in SF circles, and only Helen McNabb’s review in in Vector 148 is substantive1. Interzone’s “review” is an observation that the book existed.

Brunner makes some interesting decisions in the novel, the first of which is avoiding any mention of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, even though it’s perfectly clear that CND is what Brunner had in mind. As featured on the back cover, the Guardian review knew what Brunner was thinking of.

CND invented the kind of campaign which the US peace movement was to mobilize against the Vietnam War … John Brunner’s is the first novel to convey the heady excitement, the political drudgery and the flavour of that movement — Martin Walker

But within the covers, there is no Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, but rather a campaign for disarmament known as Liberty.

Brunner also takes the bold step of selecting as protagonist a fellow whom one has hardly met before being tempted to lob an empty boot at him. Micky has his sterling qualities… well hidden behind an abrasive surface. Likewise, his fellow strivers at Liberty are a colorful lot, with a wide range of quirks… sometimes even competence.

One of the astonishing aspects of the work is the absence of overt governmental opposition. Members of Liberty are forced by circumstance to interact with police on a number of occasions, as victims and as inadvertent receivers of misappropriated goods. The police are not notably useful, but they’re also not looking for an angle to arrest everyone. A cynic would speculate that this is because Liberty has no chance of achieving change. Letting people participate allowed them to feel as if they were accomplishing something… and it kept them out of the clutches of the World Peace Council.

If I had read the novel without being aware of when it was actually published, I would have guessed it was written before Thatcher’s time. Brunner tries his hand at various stylistic flourishes, less successfully than in his late 1960s, early 1970s works.

[Added September 24, 2024]

Jad Smith’s John Brunner explains why the novel feels like an early work. It is an early work. Various publishing misadventures delay publication from the early 1960s to 1988.

One detail rang oddly familiar, having to do with the charmingly convincing fellow who saddles Liberty’s with illicitly acquired goods.

Your psychopathic liar is often so skilled that you have to know him some considerable while before you even suspect his veracity. Then, quite often, the fear of some unpleasant revelation causes him to elaborate his constructs past the point at which they can be controlled, and the whole shebang comes down like a house of cards. Unfortunately this seldom has any — ah — educational effect on the sufferer; he simply invents something fresh.

There’s a name on the tip of my tongue.

Days of March is out of print.

1: David Redd’s review in Relapse, Autumn 2012 looks substantial… but having been published in 2012, readers would have seen it long after the Brunner was out of print.