Saturday Night Dark Masquerade

The Taking of Satcon Station (Asher Bockhorn, volume 1)

By Jim Baen & Barney Cohen

31 Oct, 2019

Barney Cohen and Jim Baen’s The Taking of Satcon Station is an SF mystery. It is also the sole Jim Baen novel of which I am aware. This is not entirely a bad thing.

Despite the best efforts of UN red tape to impede space enterprise, a century of development has seen the building of space facilities spanning Earth orbit to the Asteroid Belt. Once the US Space Command enforced the rules. Now that is the domain of Fleet Agents like Bockhorn, working for space concerns like MexAmerican & Pacific.

As the book opens, Bockhorn is stubbing out his cigarette before disembarking at Satcon Station. In its day, Satcon was a hotbed of cutting-edge research. Most people would say those days are long behind the eighty-eight-year-old station. Most people would be wrong: there’s a very bold project underway on Satcon. Bockhorn is going to find himself up to his ... let’s say eyebrows... in it.

Most of Bockhorn’s work is dealing with stowaways and truants skipping out on their contracts1. This case is different. MA&P has told Bockhorn to report to statuesque T.J. Janes (odd, as she’s not an MA&P employee). The case: reporter Lauren Potter has vanished.

Janes believes that something untoward has happened to Potter. Bockhorn isn’t clear why she believes that. The attractive reporter could have simply moved on to another station without reporting back to her superiors. But MA&P orders are MA&P orders, so Bockhorn commences a dogged search for Potter.

Some consulting detectives rely on keen insight and brilliant deduction. Bockhorn isn’t brilliant but he is persistent. He starts flipping over every metaphorical rock on Satcon to see what jumps out at him. It’s the sort of approach that leaves a Fleet Agent the target of violent men anxious to convince Bockhorn to go home. Some detectives deal with that sort of thing by being nigh-indestructible. Bockhorn relies on having more extremities than the other side has time to break.

An increasingly battered Bockhorn discovers he finds himself in a hotbed of shady deals, mooks, goons, gunsels, seductive molls, muscular space-lesbians, depraved bisexuals, corpses, misguided infatuations, and flagrant Maltese Falcon homages, all presented in Male-Gaze-o-Vision. But what does it all add up to? And can he stay alive long enough to put it all together?

~oOo~

If you do track down a copy of this, bear in mind that Bockhorn himself admits he’s not a thinker. He’s more like a glacier that is slowly grinding down the opposition. Still, a number of his decisions suggest that the reason he has not been promoted in decades is not because he’s unusually useful to MA&P at his current rank but because he is unsuited for jobs more demanding than leg-breaker. This is supported by the fact that in the Cohen-penned sequel Blood on the Moon, Bockhorn completely fails to solve an important case because he gets distracted by a tangential plot thread.

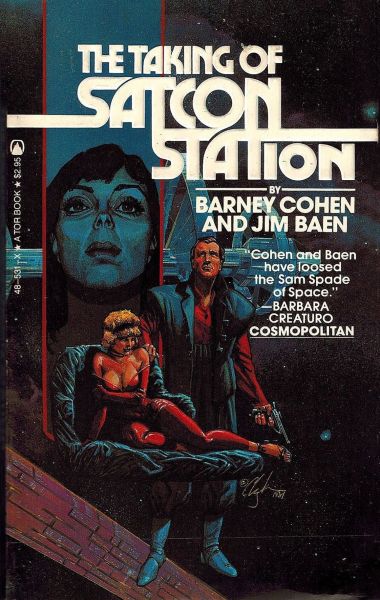

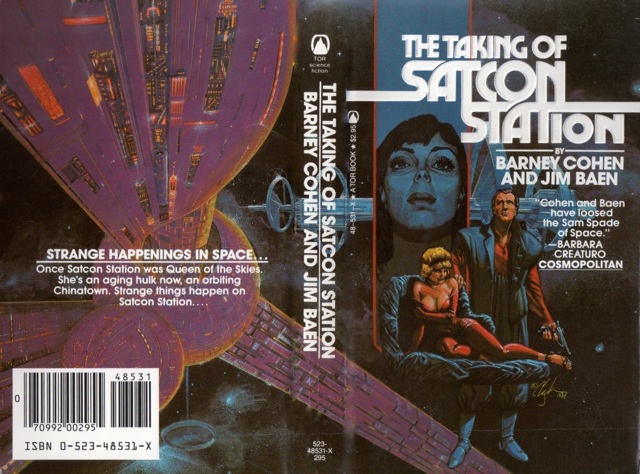

The Taking of Satcon Station was published by Tor, a company that usually demands a certain level of technical expertise from the cover artist. Still, one can see in Howard Chaykin’s illustration the basic elements of a cover philosophy that would follow the lead of this Tor cover—

—and result in this Baen cover:

Guy with a weapon, surrounded by lounging dames. Giant shoulder pads and weird nostrils optional. Chaykin is far too good at his craft to be a Baen cover stalwart, but he provided the elements which lesser artists could ineptly imitate.

Time has not been kind to this novel. To be honest, it started off at a disadvantage since the authors hewed more closely to their Black-Mask-era inspirations than they should have in a 1982 novel set in 2087. I’ll grant that few people in the early Reagan era foresaw that smoking would become unfashionable or that the Soviet Union would collapse2. That said, few 1982 novels offered amiable, elderly negro janitors speaking in colourful argot. Presumably he is only there because the authors couldn’t work out how to justify a Pullman Porter in space.

Like many futuristic novels, this one cannot imagine any cultural artifacts subsequent to the book’s publication date. Because it’s told in the first person and because Bockhorn has particularly archaic reading tastes, he references authors like Christie and Hammett3. It’s a bit of a puzzler that, despite his reading habits, Bockhorn never realizes that he could have outsmarted his antagonists if he had re-read The Maltese Falcon.

Still, there are some very 1980s concerns displayed here. The UN’s efforts to control space, if not thwarted, would result in endless red tape and quota systems that would force employers to hire shiftless Third World bums. UN/government bad is the idée fixe that drives a lot of the plot. It may also drive some readers mad.

The Taking of Satcon Station only had the one edition. It is not only merely out of print, it is really most sincerely out of print.

- The corporate legal system, which defends employees against any threat from the evil government, is rather like the one recently saw in High Justice. This may be coincidental or it might be a hat tip to Pournelle.

The corporate legal system is overtly homophobic: getting caught being gay in space will get someone sent back to Earth, which in turn makes gay people and bisexuals subject to blackmail. The authors make it clear that this isn’t because attitudes towards gays haven’t changed since the 1980s; it’s because the world has reverted to the standards of the 1980s. Worldbuilding win!

Other transgressions get people exiled to almost certain death in the Asteroid Belt. Presumably, there are transgressors who decide to appear gay and thus get sent to Earth rather than be sent to the Asteroid Belt. Earth is habitable.

- Admittedly, there are folks today who prefer hundred-year-old books.