Solutions Unsatisfactory

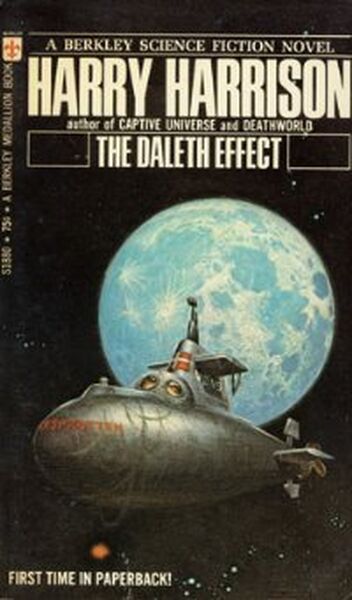

The Daleth Effect

By Harry Harrison

24 Nov, 2024

Harry Harrison’s 1970 The Daleth Effect, also published as In Our Hands, The Stars, is a stand-alone near-future1 science fiction novel.

His laboratory explodes. Danish-born Israeli Professor Arnie Klein walks out of the ruins of his lab, hastily packs, and books a flight to Belfast.

Arnie’s supposed destination is a ruse. His true destination is plucky little Denmark, from whom Arnie begs refuge.

Study of anomalous research results led Arnie to discover a new phenomenon he dubbed the Daleth Effect. The Daleth Effect has a wide range of possible applications. Arnie fled Israel because he feared that Israel, surrounded by enemies as it is, would see no alternative but to exploit the Daleth Effect’s potential for apocalyptic destruction.

Why Denmark? Because when Arnie was a boy in Nazi-Occupied Denmark, the Danes did NOT hand the Nazis every Jew they could find, but rather did their best to save as many as they could. As well, Denmark does not at present have expansionist ambitions. Denmark therefore might have the moral clarity to be trusted with the Daleth Effect.

The Daleth Effect can be used to provide reactionless thrust. Arnie demonstrates this to his hosts by converting ships into flying vessels. It takes a while to get the bugs out of the novel propulsion system, but once those are managed, Denmark has the tools needed to turn the Solar System into humanity’s playground.

A Soviet mishap provides the pretext to reveal to the world Demark’s grand achievement. Soviet cosmonauts stranded on the Moon are astounded to see a converted Danish submarine touch down near their spacecraft. The cosmonauts accept the offer of rescue.

Now aware of the Daleth Effect, all the nations of the world covet it. As the Daleth Effect is a Danish state secret—the Danish state secret — the Danes will neither share nor sell it. Secret agents of all ideologies converge on Denmark.

And if subterfuge proves insufficient? There’s always brutal violence.

~oOo~

It is important to remember that this novel was written more than half a century ago, when the geopolitical realities were very different. It could seem plausible to SFF authors that Israel might under certain circumstances resort to extreme violence in pursuit of national goals.

On that note, I’d expect the various intelligence services to take a little longer to resort to violence than they do. Ah, well. Harrison had to work within constrained page count limits.

Another book in which an author assumes that a foreign nation can be a paragon of virtue, not at all like one’s native land. This belief is most easily supportable if one avoids actually visiting the nation on which one has settled one’s hopes and dreams. Still, the case for Denmark circa 1970 is much stronger than the case for Enver Hoxha’s Albania2.

A person knowledgeable about SF history, if asked to guess where this tale first appeared, would almost certainly blurt “JOHN W. CAMPBELL, JR’S ANALOG, UNLESS THE STORY APPEARED BEFORE 1960 IN WHICH CASE IT WAS STILL CALLED ASTOUNDING.”

That person would be right.

The Daleth Effect is a Dean Drive tale. Campbell had an inordinate fondness for Dean Drives. He strongly suspected that rocket drives could never be made cheap enough for inexpensive commercial space flight. Reactionless space drives were necessary and, being necessary, must be possible! Physics proved uncooperative, but writers were quite willing to play to Campbell’s delusions.

Harrison was for the most part a reliable, mediocre author who could be trusted not to alarm readers with anything too ambitious. In this case, however, Harrison does manage to subvert the standard Dean Drive narrative. Go, Harrison.

First, Harrison leans into an obvious implication of reactionless drives that most authors employing them strive to ignore. Reactionless drives are easily converted into weapons of mass destruction [3]. Therefore it would be unwise to equip tramp freighters with Dean Drives unless you closely vet their crews or are intent on facilitating continental-scale suicide. I’m looking at you, The Makeshift Rocket.

Second, Harrison understands that the real secret isn’t how the Daleth effect works, but that it works at all. Arnie may be terribly smart, but there are lots of terribly smart people with access to the same data. Odds are that Arnie is not unique, just the first researcher to cross the finish line. I am looking at you, John Varley’s Thunder and Lightning series.

The choice Arnie makes isn’t great but then all of the solutions available are unsatisfactory. This, and the fact the second point is lost on the non-scientifically-minded intelligence community, is why The Daleth Effect could also be called a science fiction tragedy.

The Daleth Effect is available as In Our Hands, The Stars here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Apple Books), here (Barnes & Noble), and here (Chapters-Indigo).

I did not find The Daleth Effect under that title or as In Our Hands, The Stars at Words Worth Books, probably because the novel is only available as an ebook.

1: Alternate past now, thanks to the passage of time.

2: The Chevron, UWaterloo’s student paper prior to the late 1970s, loved Enver Hoxha.

3: For example, the Daleth Effect makes it possible to zoom from Earth to Mars in 39 hours. A bit of math says the peak velocity would be about 700 kilometers per second. Ek = ½ MV2, or in this case about 25 billion joules per kilogram, or about six times its mass in TNT. By the time ships get from one end of the Solar System to the other, their Ek might reach nuclear weapon energy densities. As well, Daleth Effect ships can in theory huck mountain-sized asteroids.

Thus Burnside’s advice: Friends Don’t Let Friends Use Reactionless Drives In Their Universes.