Some Other Spring

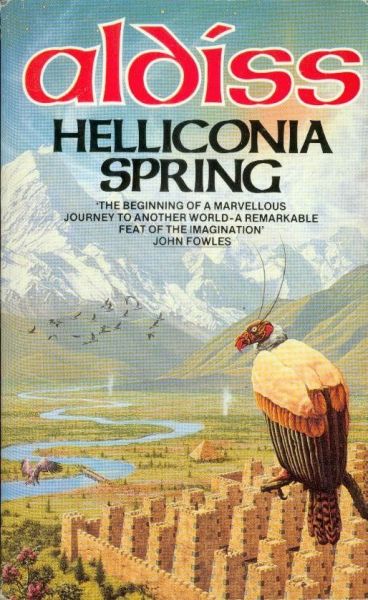

Helliconia Spring (Helliconia, volume 1)

By Brian W. Aldiss

7 Jul, 2020

Brian W. Aldiss’ 1982 Helliconia Spring is the first volume in his hard SF1 Helliconia trilogy, which, curiously contrary to publishing tradition, appears to consist of three, and only three, books.

In many respects — age, mass, density, insolation, the presence of complex organic life, even the presence of a humanoid native species — the distant world Helliconia is much like Earth. In one very significant respect Helliconia is very different from Earth. That difference has driven the course of civilization on Helliconia for longer than its sentient inhabitants can remember.

For most of its existence, Helliconia was illuminated solely by Battalix, a G4 star somewhat smaller and cool than Sol. Several million years ago, Battalix and most of its planets were captured by Freyr, a much younger A‑type supergiant, in an eccentric orbit that takes 2592 Earth-years to complete. Freyr is always far more distant from Helliconia than Battalix, but since the supergiant is far brighter than Battalix, it has had a profound effect on Helliconia’s climate, particularly when Battalix and Helliconia are closest to Freyr. Unlike Earth, where seasons are driven by Earth’s obliquity, Helliconia’s climate is determined almost entirely by the world’s proximity or lack thereof to the giant star. As the book opens, the smaller star and the planets that orbit it are approaching Freyr.

Not that the humans of Helliconia have any idea why their world is as it is. Thanks in part to the brutal cycle between too cold and too hot, the humans start each cycle almost totally innocent of their ancient history. Relics surround them but their significance is lost

Yuli is out hunting yelk with his grim father Alehaw when the pair are ambushed by phagor, the intelligent species that dominated Helliconia until Freyr’s arrival. Phagor are hostile at best. These capture Alehaw, sparing him so that he may serve as a slave. Yuli is left behind to fend for himself in the frozen wilderness, to live or die as fate decrees.

Yuli manages to survive. A series of misadventures lead him to the buried city of Pannoval. Despite Pannoval’s general lack of interest in aiding outsiders he manages to worm his way into the priesthood, a niche in which he might have lived a comfortable life. Ultimately, he rejects this possibility and leads a small party of adventurers out of the caves and back into the (imperceptibly) warming world.

Some lifetimes later, the world is a warmer place. Yuli’s descendants live in Oldorando, a village built on ruins left by a mostly forgotten civilization. A warming world sends travellers along half-forgotten trade routes. Oldorando is at a crossroads and benefits from this economic activity. Oldorando life changes from a desperate struggle to survive to one in which a lucky few can indulge their interest in what we would call natural science.

Aoz Roon, the current ruler, regards this interest in science with a jaundiced eye. Shay Tal, the woman running the scholarly side of things, is less interested in Roon that she is in her researches. Conflict ensues. Thanks to the renaissance she helps spark, Oldorando (re?)-discovers plant and animal domestication, a discovery that transforms Oldorando into a regional military power.

All of which may not matter. A deadly pestilence is sweeping the globe and may soon visit Oldorando. So may a vast phagor army determined to re-assert their former rule of the world.

~oOo~

I found it curious that while various characters rebel against narrow gender roles, nobody seems bothered by slavery except as something one should do one’s best to avoid experiencing personally.

M. John Harrison once wrote a jeremiad against world building, castigating it as “the great clomping foot of nerdism.” It’s too bad that he does not appear to have reviewed Helliconia Spring. A shame, because his fulminations would no doubt have been choice. One might have lit all Britain by their fiery radiance.

There are authors who, having lovingly created a world, treat their creation’s backstory like an iceberg, with only the most relevant portion of their creation protruding into their narrative. Others cannot resist the urge to show their work, perhaps in informative tidbits presented at the beginning of chapters, before diving into their tale. Aldiss boldly adopts a Stapledonian strategy, in which he expounds at enormous length on every detail of his lovingly crafted world. One might say that he sometimes remembers that some of the iceberg is above the water and revisits the upper portion to see what the humans have been doing, as a diversion from the serious business of stellar masses and orbital dynamics. That would a little unfair … but only a little.

Perhaps it would be kinder to say that Helliconia Spring is the story of a world warming from a deep freeze. The various characters and their struggles are merely the means by which Aldiss illustrates the process. Climate change may seem an inherently undramatic subject. No doubt this is true for Earth. Helliconia is subject to operative extremes, whose dramatic changes Aldiss reveals in great detail. And several appendices.

While Aldiss’ focus is on Helliconia as a whole, he does manage to paint vivid pictures of the cast’s brief lives. They may each be insignificant on a cosmic or even planetary scale, but each tiny spark cherishes its hilariously brief existence. Not exactly a comforting read, but then, British SF of the time was notably dour2.

Helliconia Spring is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Book Depository), and here (Chapters-Indigo).

1: Hard SF except that the inhabitants can commune with their dead ancestors. How you could handwave that as science is unclear.

Oh, and it’s also not at all clear how such a humanoid species evolved on Helliconia given that all the other animals have very different bauplans. No, the humanoids aren’t displaced Terrestrials; they evolved locally. Or at least that’s what the book says.

2. If UK SF was dour at that time, can we blame Margaret Thatcher (prime minister 1979 – 1990)? Or was it simply losing their Empire?