Strange Things Happen

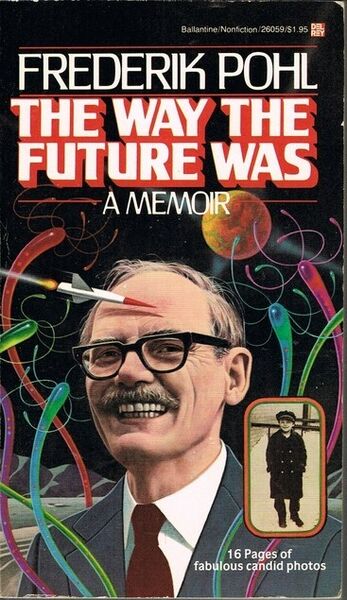

The Way The Future Was

By Frederik Pohl

30 Mar, 2025

Frederik Pohl’s 1978 The Way The Future Was is an autobiography. Because of Pohl’s diverse roles in the science fiction field, Future is also a good introduction to the history of American1 science fiction from the 1930s to the late 1960s.

Back when I was a teen, I knew who Pohl was. He was the unimaginably old writer who, before I was born, had written a lot of SF that I enjoyed (in reprint), who had somehow overcome the inevitable cognitive erosion imposed by advanced age to write some of the best SF of the modern era… which is to say the 1970s.

In 1978 he was about five years younger than I am just now.

I was terribly distracted while reading this by the mystery posed by my copy of the hardcover. It’s an odd artifact, with uneven, roughly trimmed pages. I guessed that it was an SFBC edition but no: the ISFDB says that the SFBC edition was 270 pages long and the book in hand is 312 pages plus ancillary material, which means it is the Del Rey edition2. Which in turn means that seventeen-year-old me forked over nine or ten dollars for this (about $45 in 2025 currency), on top of which I also purchased the $2.50 paperback a year later. The book is more than worth getting but why, if I bought the hardcover, did I then buy the paperback? Portability?

Future was one of a number of autobiographies and historical accounts of SF that came out around this time. Collectively they stressed that writing wasn’t a mysterious process that happened out of sight, via means that ordinary mortals could not ken. Rather, it was a business and avocation (almost) that anyone could do, given time, effort, and determination.

In retrospect, I see that this book (and ones like it) also make it clear that long publishing careers are a matter of surviving setback after setback. If investors aren’t suddenly killing half the American distribution network, Hitler is invading Poland. Therefore, be ready, as Pohl was, to reinvent yourself over and over.

Future is entertainingly written and provides a pleasing overview of SF from the 1930s to 1970s. One gets the impression that Pohl was a terribly nice man (or at least aware that caustic comments about co-workers in a tiny field could impact future prospects). Thus, he carefully avoids dishing too much dirt on his colleagues, as long as those flaws didn’t involve not paying on time. Such foibles that get mentioned are those that can be framed as amusing.

The notable exception to the tone concerns Pohl’s children, or rather that subset who did not survive childhood or who experienced lifetime consequences from childhood maladies. Life before modern medicine could be grim, and in some cases, short.

Which is to say I’d recommend Future if it were in print… but at the same time, I am pretty sure that this is a fairly narrow, carefully curated history of SF publishing. There’s a lot of material outside the frame, material with which Pohl does not engage. Think of this as a starting point.

1: As It Was In The Beginning

Pohl contextualizes his early encounters with SF in the good old days of the Great Depression, when Americans were still free to starve to death under bridges if they so chose.

This is inadvertently also a snapshot of the 1970s, after LBJ established the Great Society but before Reagan et all began chipping away at it.

2: Let There Be Fandom

Having discovered SF, Pohl wanted to talk to other people about it. Happily, Hugo Gernsback (who arguably invented SF, at least as a marketing category) kickstarted US fandom in an ill-fated attempt to boost magazine sales.

3: Science-fiction Samizdat

Commentary on early fanzines, the AO3 of the day. These were amateur productions with circulations ranging from miniscule and up, with no particular quality control. However, a number of pros came up out of the fanzines.

4: Boy Bolsheviks

Pohl and some of his friends discover communism. Among other things, this gives rise to Michelism, which is referenced but not really explained in detail, and to the Exclusion Act (see next chapter).

Michel thought SF could have a positive transformative effect on society (despite all prior evidence to the contrary) and called for:

Be it moved that this, the Third Eastern Science Fiction Convention, shall place itself on record as opposing all forces leading to barbarism, the advancement of pseudo-sciences and militaristic ideologies, and shall further resolve that science fiction should by nature stand for all forces working for a more unified world, a more Utopian existence, the application of science to human happiness, and a saner outlook on life.

Which was (of course) solidly voted down.

The problem with using SF fans to reshape society is that, sure, they’ll embrace some new social arrangement… for as long as it entertains them, after which they will move on to the next thing.

5: The Futurians

The genesis of the fan group to which Pohl belonged. Many of the names were unfamiliar to me in 1978 and are no doubt even more obscure now. However, others were familiar (Asimov, Blish Merril, Pohl, and Kornbluth, for example). More importantly, a number of the members went on to become influential editors (Pohl, Merril, Knight, and Wollheim); it’s hard to overstate how much impact the Futurians had on what SF became.

I had thought Lester Del Rey was part of this group, but he seems to have come along just a bit too late. He was part of the Hydras.

Here and there Pohl provides advice for would-be writers. In this chapter he strongly urges writers (or at least the ones who are determined to take courses in pursuit of their careers) to study spelling, punctuation, grammar, and touch-typing. Someday, I should do that.

6: Nineteen Years Old, and God

Pohl gets his first job as an editor. He also gets married for the first time, to Doris Baumgardt.

7: My Life as a Cardinal Man

Divorced, Pohl pesters the American armed forces into drafting him so that he can fight the fascists overseas. This goes swimmingly well for Pohl, in the sense he emerges from the experience alive, untraumatized, and without lingering disabilities. Pohl marries Dorothy LesTina despite the significant impediment that she was an officer, he but an enlisted man, and fraternization between ranks was forbidden3.

8: Ten Percent of a Writer

Pohl becomes an agent, and in so doing pioneers a brand-new way of tackling the agent gig, one that leaves him deep in debt. A foray into advertising pays better, and all it costs is a man’s soul.

Now divorced, he marries Judith Merril… whom he later divorces.

I completely forgot the timing of the implosion of Pohl’s agenting career. Thought it was late 1950s but actually it was 1953.

Something that had not changed by the 1980s, and is probably still true now, is that usually one has no idea if ads have any effect on sales4 and if they do, which ads had the effect or why. There are exceptions. For example, postcards with the slogan:

HAVE YOU GOT A BIG BOOKCASE? Because if you have, we have a BIG BOOK for you…

Sold a lot of big books.

9: Four Pages a Day

Pohl embraces the carefree life of the freelance writer. Pohl marries Carol Metcalf Ulf.

10: The Finest Job in the World

Pohl becomes editor of Galaxy Magazine, and If, and later Worlds of Tomorrow. He is successful enough to take home a rack of Best Editor Hugo Awards.

11: Have Mouth, Will Travel

Pohl embraces public speaking.

12: How I Re-upped with the World

Pohl has his magazines yanked out from under him and has to reinvent himself yet again.

Unfortunately, this chapter does not discuss his career as an editor for Bantam, which is a great pity because I’d love to know how he knew that Delany’s Dhalgren would be a best-seller.

Fred and Carol Pohl separated in 1977 and divorced in 1983. The fact that the separation isn’t mentioned (although mid-life crisis marital issues are) suggests to me that Future was finished some time before 1977.

I don’t understand the thought processes of people who marry and divorce over and over and over. Wouldn’t they conclude, three or four marriages in, that maybe their core competencies don’t include sustained marriage? Aren’t there more productive ways they could spend their time? Do people not consider comparative advantage when arranging their lives?

That said, someone on Bluesky observed Pohl’s “books include women, and they actually read like real people, not sticks with boobs!” Pohl’s comments on his wives suggests why that might be:

I am hesitant to speak of “my ex-wives” as if the term defined them as a class. The principal thing that the ladies I have been married to (and some ladies I have not been married to) have in common is that each is very much an individual, with talents and graces far beyond the usual allotment. I keep running into people who speak of lives damaged by mates so malevolent and self-centered that the marriage is a constant pain. It has never happened to me. It is hard for me to believe that these closet beasts and termagants exist. Barring the odd dissonance in the relationship — well, maybe barring a lot of dissonances — the women who have shared any part of my life have each been a treasure, and a joy.

If you want to write believable women, it helps a lot if you can perceive them as people, and it won’t hurt if you actually like them.

***

As far as I can tell, The Way the Future Was is completely out of print, even in ebook form.

1: America delenda est.

2: It seems to be a first edition, but those are not especially valuable, unlike my copy of Butler’s Survivor.

3: Which reminded me of a funny thing that happened to my paternal grandfather. At one point he was seconded to the Royal Navy as an American civilian advisor. During his first cruise, it was discovered that regulations made feeding him problematic. He couldn’t eat with the black gang, because he was a civilian. Couldn’t eat with the officers, because he wasn’t an officer. As starving him to death would have been counterproductive, he had to eat all his meals by himself.

4: As far as I could tell in the 1980s, the only ads that brought in enough business for my game store to justify the cost were Yellow Pages ads. Every other ad cost more per customer than they would spend.