Such a Timeless Flight

Universe: The Roleplaying Game of the Future

By John H. Butterfield & Redmond A. Simonsen

20 Mar, 2022

Having surpassed — they hoped—Dungeons and Dragons with their Dragonquest roleplaying game, Simulations Publications, Inc set out to challenge the dominance of GDW’s Traveller with their own science fiction roleplaying game. Heading the SPI team: John H. Butterfield and Redmond A. Simonsen1.

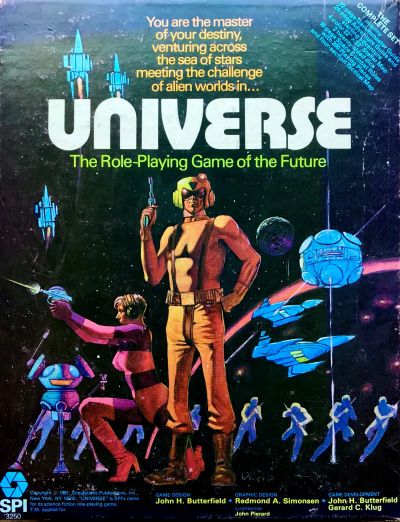

SPI released Universe: The Roleplaying Game of the Future in March 19812. What wonders were concealed within the deluxe box?

Despite box design being somewhat more primitive in those days, the cover

gives an accurate impression of the contents: a Gamemasters’ Guide, an Adventure Guide, a Stellar Map, two dice, and Delta Vee, a minimal space war game.

Whereas Traveller was set in a distant future and offered characters of primarily military backgrounds, Universe was set in the 24th century. It offered twenty-three professions, only seven of which were military. Whereas Traveller featured alien civilizations, Universe did not (although a later magazine article offered one). Whereas Traveller’s Imperium was surrounded by rivals, Universe’s worlds were under the umbrella of the Federation of Planets.

Universe did not thrive. This was only partly due to the fact that SPI wasn’t making a profit (the biggest nail in the coffin was a large loan from its mortal enemy, TSR, a move roughly on par with appealing to Genghis Khan for assistance with border security). It was also due to problems with the product.

While the box itself was pleasingly sturdy, the saddle-stitched books within were short and flimsy3. The rules were laid out with all the clarity and panache of a legal document4. Upon rereading the rulebook after a hiatus of forty years, I noticed niggling inconsistencies: some skills accrue experience when the dice roll 0 or 1, some when one is successful, others when the player rolls a 1 and so on. As I recall, actual play suggested that some of the rules could have been better play-tested than they actually were. I can’t decide whether a quirk of the skill-check mechanics — that one’s odds of success in combat were increased by one’s skill level squared — was poorly thought out OR a cunning way to represent newbies and veterans on the same compact scale. Whichever it was, it encouraged people to specialize in a few skills rather than a broad range.

There was no index in the boxed set. The second (perfect-bound trade paperback) edition did have one.

Various details reflect the era in which Universe was designed. For example, the default term for human is man. There are no pre-made settings beyond a few sparse comments about the Federation; there’s a world generation system instead. Game companies of the era believed that gamers preferred to create their own settings rather than rely on pre-made ones. While the values rolled are 1 – 10, the dice are twenty-sided because at this point nobody made ten siders (and while my d20s are mixed with the rest of my dice, I’d bet they were low quality dice because that was what was available in 1982). The clunky game mechanics may seem oddly disparate to us, but that was how game design worked way back when, in the days when “10%+MP+SL2=Target’s MP2″ was just clean fun. Oh, how we dreamed of the simple elegance of THAC0. Trust me, that’s hilarious.

Which is not to say that Universe didn’t have some interesting, even impressive features. The most impressive is the Stellar Display, a 22” by 33” poster-sized map of a sixty-light-year-diameter sphere of space centred on Sol. SPI had rejected Traveller’s two-dimensional approach and opted for three dimensions, which (for a certain flavour of nerd) were mind-blowing. Not only was the map filled with useful information, but it was also very pretty.

Overall, Universe falls a little short: a bit bland, a bit cumbersome, without much — aside from that glorious map — to tempt people away from Traveller. Pity, because it feels like there’s the seed of something better under the legalese, forbidding math, and ponderous game mechanics. One wonders to what extent GDW was inspired by Universe when they designed their Traveller 2300 (later renamed 2300 due to brand confusion with the unrelated Traveller). There are some parallels, as well as details that might be an attempt to avoid Universe’s problems6. Ah well. To resolve that question, I’d have to reread 2300 and what are the odds I still own a copy and know where it is?7

Universe is extremely out of print.

Now for the nitty-gritty.

Gamemasters’ Guide

There are a few hints on setting up a background and a long foray into the character creation system. Like that of Dragonquest (see link above), this system was a mixture of random and design elements. I recall that the process seemed convoluted, but it did produce an interesting variety of characters. The system also featured a rather cunning grid-based method of handling environmental skills (with the peculiarity that cities were not an environment but a skill).

The booklet then provides a list of skills (most non-violent!), guidelines on skill use, and rules for experience. This is followed by a section on robots, one on standard equipment (details of which scream that this was written in an age of mainframes5), a rather uninspired world generation system (whose mapping system I outright hated), rules for taking action, and finally, rules for spaceship design and space travel.

The core starship design system was surprisingly quick and flexible for an SPI design and would be worth imitating today. However, one aspect stood out. FTL required the services of a psionic adept, as did interstellar range communicators. Psionic adepts were rare, at least in the general population. Because they were so useful, nay, absolutely necessary in the game, not to mention being magnets for power gamers intrigued by the potential to play a character who could mind-control people at continental ranges (see playtesting, lack of) an unusually high fraction of player characters were psionic adepts.

OK, maybe two aspects stood out: ships were powered by fission power plants (well, “radioactives”) rather than fusion, despite which their performance was every bit as implausibly good as other companies’ fusion drives.

Adventure Guide

This mainly concerns encounters and mishaps. An introductory adventure is included.

Stellar Map

This was a colour-coded map of the stars within thirty light-years of Sol, with the X and Y coordinates displayed in the usual manner and the Z indicated with colour. Numerical coordinates were provided, along with a table indicating distances between major systems, as well as other handy text blocks.

Delta Vee

This was a compact, sixteen-page booklet setting out the rules for a space wargame. Two hundred pieces and a four-sheet hex map were also provided. I played it more than I did Universe. As I recall, any players who opted for ship combat regretted their choices; combat could be very deadly.

1: More complete credits:

- John H. Butterfield: Game Design and Development, Project Coordination.

- Redmond A. Simonsen: Design of Physical Systems and Graphics.

- Gerard C. Klug: Co-Development and NPCs.

- Edward J. Woods: Creatures and Advice.

- David McCorkhill and David J. Ritchie: Development Assistance.

- Robert J. Ryer: Rules Editing.

- Robert E. Kern, Linus Gelber, Justin Lietes, Julie Spangler, Ian Chadwick, Wes Divin, Mark Barrows, and the Olympia Gaming Association: Additional Testing.

- Manfred F. Milkuhn: Art Production Management.

- Carolyn Felder, Ted Koller, Michael Moore, and Ken Stec: Art Production Management

- John Pierard: Cover and Interior Illustrations.

2: This release date just barely qualifies this game review as a Tears Review.

3: Fragility of rulebooks: the first thing I did on getting back to campus was to photocopy the rulebooks to avoid wearing them out.

4: I’m mocking the rulebook, but I must admit that it was a sincere effort to present the rules in an unambiguous, clear way.

5: Universe used computer rules which seem to have been inspired by the era of mainframes. That makes it more modern than Traveller, which used rules inspired by the era of vacuum tubes.

6: Due to the aforementioned odd skill-rating system, Universe had a heck of an edge-of-the-map issue. While tyro star pilots would be well advised to stick to small jumps between systems they know well, a top level, highly experienced navigator can safely reach the centre of the galaxy (much farther than the edge of the mapped bubble) in a surprisingly short period of time. Time was limited (for the most part) by how quickly the ship’s engineer could swap out burned-out jump pods and swap in new ones.

7: As it happens, excellent odds that I still have it and could find it. Precisely 100 percent.