Take Passage Overland

Hiero’s Journey (Hiero Desteen, volume 1)

By Sterling E. Lanier

11 Oct, 2020

1973’s Hiero’s Journey is the first volume in Sterling E. Lanier’s Hiero Desteen series.

7476 AD: Accompanied by the intelligent bear Gorm, Secondary Priest-Exorcist, Primary Rover, and Senior Killman Hiero Desteen rides his telepathic war moose Klootz into the heart of darkest former America in quest of a fabled computer. Whatever a “computer” might be.

Spared atomic doom in the great Death because their communities were too insignificant to exterminate, Métis and Indian survivors founded the successor nations of the Metz Republic and the Otwah League under the benevolent guidance of the Church Universal1.

The condition of the continent beyond Kanda’s borders is largely a matter of rumour conveyed by roving traders of dubious trustworthiness. Mutants abound, thanks to the fallout that followed the Death. No all are so-called Leemutes, hostile monsters. Enough are monsters that the priest’s chances of survival are rather slim.

All of which is not enough to keep Hiero from rescuing a beautiful woman about to be sacrificed to evil birds. This bold decision may not advance his quest, but saving Luchare, royal princess of D’alwah, does wonders for his love life.

Irradiated nature is not Hiero’s greatest enemy. Dark forces are at work across North America, determined to isolate and destroy the folk of Kanda. Not all scientists died with Western civilization. Their descendants yearn only for power and the subjugation of all people under their malevolent rule. Against Science! What hopes have Hiero and his allies?

~oOo~

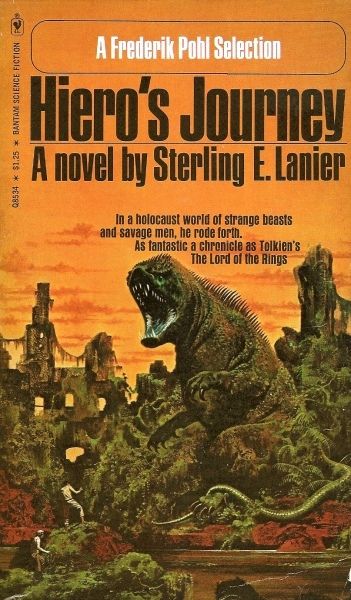

MOOSE!

While early editions overlooked the obvious popularity of moose, later editions took care to feature them on the cover.

“7476 AD” is not a typo. Lanier hews to the Jack McDevitt historical model (or rather, McDevitt hews to Lanier’s), which is that spans of time comparable to the time since the founding of Egypt’s first Dynasty will have surprisingly little effect on vocabulary or culture. For that matter, machines five millennia old need only to be turned on to begin working again,

You might think stumbling across a princess in the wilderness is pretty unlikely2. Hiero certainly does.

“I beg your pardon, your ladyship,” he rejoined acidly. “You were, I suppose, a princess in your own mighty kingdom, perhaps betrothed to an unwelcome suitor and forced to flee as a result, rather than marry him?”

[…]

“My God, you’ve grabbed up the fantasy of every girl-child who has first heard the legends of the ancient past. Now stop trying to waste my time on this silliness, will you?”

His skepticism is one of the very few times Hiero is incorrect. One of the other times also involves Luchare: when he first meets what he takes to be a fifteen-year-old, he rejects the idea of marrying her — his sort of priest is not required to be celibate — but once assured by the woman intent on winning him that she is a mature woman of seventeen, he reconsiders.

There are white characters in this book, but all of them with lines are villains. All of the heroic humans are Métis, Indian, or black. The bad guys in contrast live at high risk of sunburn. At least the human ones do.

This reads like something a Canadian might write. Canada, even in this far future, is an oasis of peace, order, and good government, whereas everything south of the border is an uncharted wilderness of violence, barbarism, ignorance, and entrenched cruelty, ruled over by an undemocratic cabal of pallid, malevolent tech-bros. Also, MOOSE!3 One might therefore be surprised to find that Lanier was American4 and born in New York City.

It is a pity that the novel is not very good. One might go as far as opining that it’s moderately bad. Hiero and his pals are GOOD (if, in the case of Luchare, not all that useful, although one gets the sense the author thought he was writing an Action Girl). Those who oppose him are EVIL. Although one is supposed to believe the good guys could lose, fate clearly sides with Hiero; when his own talents are not enough to save him, a deus ex machina will arrive.

Only the fact this novel predates the table-top roleplaying game by half a decade prevents me from unhelpfully describing this as Gamma World: The Novel. If you have played Gamma World and were looking for reading material of an unchallenging sort, you might consider this.

If you can find a copy. As far as I can tell, Hiero’s Journey is long out of print.

1: The Protestants rejoined the Church. What precisely happened to Canada’s Jews is unclear but it’s a plot point that Kanda has no Jews, because Luchare has to explain who the People of David are. Aside from the rare Eleveners (enigmatic wanderers), Kanda seems to have no religious minorities to speak of, which is pretty creepy.

2: Age-old trope of adventure stories: the rescued princess. I suspect that Lanier grew up reading about John Carter of Mars and Dejah Thoris, the princess he rescued.

3: Technically it is a “morse,” but morses are derived from moose. Or would morse be the plural of morse, the same way that moose is the plural of moose?

4: Historical detail of which I was previously unaware: Lanier was the Chilton editor who acquired Dune, a bold decision for which he was fired when the book underperformed.