That’s How It Goes

Showa: A History of Japan

By Shigeru Mizuki (Translated by Zack Davisson)

7 Aug, 2024

0 comments

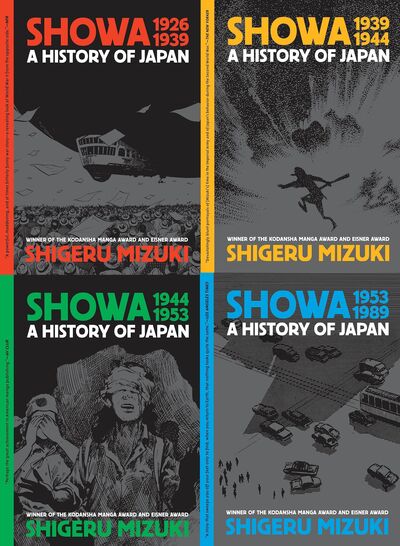

Showa: A History of Japan is Shigeru Mizuki’s epic autobiographical historical manga covering the reign of Japanese Emperor Hirohito. First serialized from 1988 to 1989, Zack Davisson’s English translation was published in four volumes: Showa 1926 – 1939 (2013), Showa 1939 – 1944 (2014), Showa 1944 – 1953 (2014), and Showa 1953 – 1989 (2015).

1922: the Mura family’s least promising son, Shigeru, is born. He is given a front row seat to many lamentable events.

1923: the Great Kantō earthquake. The human costs (both from the earthquake and fire, and from the anti-Korean riots that followed) were immense. The financial consequences were still playing out when Emperor Hirohito ascended to the throne on December 25, 1926.

The men who run Japan prefer short-term solutions to long-term problems. They are all too prone to convincing themselves that what they want to be true is true. When the inevitable nasty consequences ensue, they engage in strict censorship and increasing authoritarianism.

A latecomer on the global stage, Japan sees no reason it should not have an empire as mighty as any European empire. Indeed, the arena for empire-building is at Japan’s doorstep. Korea has already been conquered. Adding China, and as much of the rest of Asia as possible, is only logical.

What should have been a short sharp war drags on and on. Setbacks provoke further escalation from Japan. By the time Shigeru is a young man, the Asian war has joined other grand conflicts and the whole world is convulsed with war.

Japan’s young men are expected to do their bit for Japan. Shigeru will not escape.

Shigeru is no natural warrior; he is relegated to serving as bugler. Chafing at this role, he requests a transfer and despite repeated hints from superior officers that this is a terrible idea, obtains it. No more dreary music for Shigeru! Instead, he gets to fight on the front-line of the grinding war in New Britain.

The odds do not favor survival. Nevertheless, Shigeru does not die. Starvation, beatings, crocodiles, disease, and dismemberment can’t (quite) kill the young man. His reward for surviving: a return to a post-war Japan, a nation that has never had a place for him.

~oOo~

If you’ve ever wondered how nations embraced authoritarianism, this manga provides one answer: surprisingly easily, in part because other solutions looked harder. As Mizuki tells the story, FOMO played a role as well. The people running Japan assumed the people embracing militaristic authoritarianism knew what they were doing and didn’t want to be left out. It’s like NFTs, except with mass graves.

The author/artist can create realistic art when he wishes, but he seems to prefer overtly cartoonish styles. As a consequence, readers may find it hard to work out exactly what the omniscient narrator Nezumi Otoko is supposed to be. A rat, apparently, one of the characters from the author’s yokai-focused manga, GeGeGe no Kitarō. One perhaps unintended benefit of such artistic choices is that Mizuki’s cartoonish New Britain natives, who might be highly problematic in other contexts, are no more grotesque than the artist’s depictions of Japanese people.

Because he is covering sixty-two years in just four volumes, Mizuki opts for a flickering fast-forward presentation of recent Japanese history, copiously annotated with scathing commentary on Japan’s (and other nations) missteps and shortcomings1. Enough detail is provided that readers unfamiliar with the period can understand (in general, not in detail) recent Asian history, at least that part that pertains to Japan.

A speed-run through the Second Sino-Japanese War and its aftermath might fail to engage the reader if presented as impersonal history. Because we see everything through the eyes of one fallible but engaging protagonist whose entire life is shaped by the Showa era, we care.

Many authors of autobiographies are tempted to present themselves as favorably as possible, focusing on their successes and laudable qualities while avoiding discussion of their less admirable moments. Mizuki is disarmingly honest. He shows himself as easily distracted, lazy, and self-centered. He’s an idiot who willfully transfers into a deathtrap, a fellow for whose eventual wife and children one can only feel sympathy. The success he enjoys towards the end of the work is long in coming.

The obvious comparison is to Larry Gonick’s History of the Universe, another high-level tour of history. Gonick and Mizuki have very different styles and tone, but I think readers who like one should like the other.

I found it rather depressing that so many of the events in the run-up to the Second Sino-Japanese War seem to be repeated in current events. Could calamities of similar scale await us? Haven’t we learned anything from history?

Showa 1926 – 1939 is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Apple Books), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Chapters-Indigo), and here (Words Worth Books). The other volumes will be nearby.

1: Despite Mizuki’s disapproval of the wartime Japanese government, wartime atrocities, while mentioned, are somewhat soft-focus. Perhaps he is just sparing his readers? Mind you, he found room to mention his brother’s conviction for a Class B war-crime, which he could easily have omitted.