The long con of Oliver VII

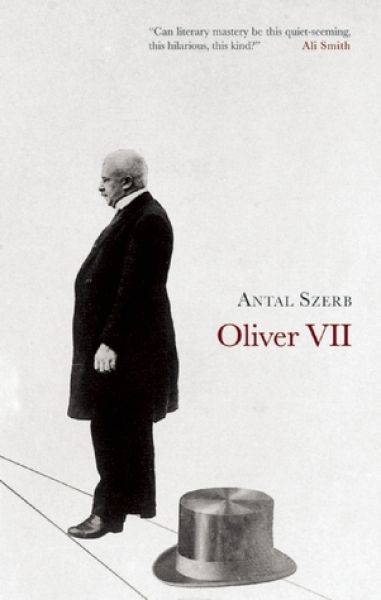

Oliver VII

By Antal Szerb (Translated by Len Rix)

21 Jan, 2015

0 comments

Antal Szerb was a major figure in the Hungarian literature of the first half of the 20th century, and his 1942 novel Oliver VII is a perfect confection of a comedy. It seems a great shame, therefore, that the novel was not translated into English until 2007 — although Len Rix’s translation is a fine one — and an even greater shame that the forty-three-year-old Szerb, who refused to be run out of his homeland by jumped-up thugs, was beaten to death by a fascist in 1945.

Pity poor King Oliver VII of Alturia. Thanks in large part to the bold modernization carried out under his father, the late King Simon II, Oliver VII’s Alturia stands on the brink of disaster. It is insolvent and roiling with revolutionary discontent. There is a possible financial solution — if the ambitious Norlandian financier Coltor is granted total control of Alturia’s wine and sardine industries and Oliver agrees to an arranged marriage to the delightful Princess Ortrud of Norlandia, Coltor will underwrite the kingdom’s shaky finances. But details of the secret arrangement have been leaked, inflaming public outrage in Alturia, and conspirators led by the Nameless Captain are plotting to depose Oliver.

The Captain’s coup is carried off with remarkable efficiency for Alturia, a nation that has never set a lot of stock in doing things quickly or well. This is in large part due to the fact that Oliver VII himself is the Nameless Captain. The bloodless coup allows Oliver an acceptable exit from the constraints of his life as King, leaving him free to survive as he imagines the common folk do, using only his skills, wits, and fortune … plus a little help from his faithful minion, the painter Sandoval.

Discarding the name Oliver in favour of the more plebeian monicker Oscar, the former King reinvents himself. He finds new love in the mercurial Marcelle. In order to get closer to the young woman, he convinces her boss, Count St. Germain, that Oscar is a conman like the Count himself.

At this point, the Count is not a successful conman. His protracted attempt to sell a fake Titian to a man who turns out to be a Titian expert1 has been fruitless, and his coffers are dwindling down to their last centismo. Then chance presents a new opportunity: a lucrative con involving an ambitious businessman, a troubled kingdom whose revolution has not gone according to plan, and a deposed monarch rumoured to be somewhere in Africa.

For the con to succeed, all Oscar has to do is to somehow convince the world that he is this missing king, this Oliver VII, whoever that may be.

At just under 200 pages, this is not a long novel, Szerb sets the tone on the first page with this bit of business involving a smitten Count of advanced age and the young dancer on whom the count has set his monocle:

The Count drank himself into a stupor most evenings, but, not being a man of narrow principles, he had no objection to drinking in the afternoon as well. In fact, he had probably been at it that morning too — it was hard to say quite when he had begun: normally he would have known better than to appear before so large a gathering in the company of a little dancing girl of such dubious reputation. (In those years before the war women still had such things.) Luckily the trellised bower they were in offered a shield from prying eyes.

“My gazelle!” he murmured amorously. The little dancer acknowledged this compliment with a guarded smile.

“My antelope!” he continued, developing his theme. He sensed the need for yet another animal, but could think of nothing better than a pelican.

Alturians as a people are romantic and often foolish. While Oliver/Oscar certainly partakes of the national character, he’s no dummy and he can be competent when he cares to be. Given the skillful way he manages the coup against himself and the comfortable way he wears the identity of the Nameless Captain, Oscar isn’t really lying when he convinces the Count that Oscar is a fellow conman. However, he is probably rather startled at the destination towards which his new career is leading him.

As a Hungarian, Szerb would have been familiar with the ambitions and disappointments of revolution and counter-revolution; this novel is a lot funnier and considerably gentler in spirit than I would expect from a Hungarian of this period2. Having read War with the Newts recently, I am struck by the passing similarities between Čapek and Szerb, both born in the same doomed Austro-Hungarian Empire and both fated to be ground underfoot by the Central European villains of the first half of the 20th century. Similarities and yet … how different their literary reactions to their circumstances were.

One aspect that I was struck by was the absence of antagonists in this book. Characters have conflicting agendas but aside from some poorly aimed irritation at rich Americans, there’s not much in the way of malice or irritation in this. Even Coltor isn’t a bad guy, just an excessively ambitious one. One of Oliver’s achievements is to find a path that leaves as many people as possible pleased with the outcome.

Oliver VII is a fine example of the Ruritanian Romance, albeit one that does not take itself quite as seriously as others. It and other works by Szerb are available from Pushkin Press.

1: The expert, an obnoxious American named Eisenstein, comes unfortunately close to an anti-Semitic caricature:

Mr. Eisenstein was just the sort of person you might imagine from his name: a stout, slovenly man with a large chin and nose, and a wide, sarcastic, self-satisfied grin, perhaps the permanent defence of a naive individual against the world.

Although it may be significant that the count and his team completely misread their mark, who seems to be very amused at the attempted con.

2: Bear in mind that I am in no way familiar with Hungarian literature of any period.