The State of Things

Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue with His Century

By William H. Patterson

19 Aug, 2025

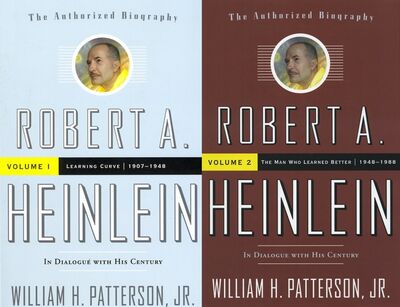

William H. Patterson’s 2010 Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue with His Century, Volume 1: Learning Curve (1907 – 1948) and 2014 Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue with His Century, Volume 2: The Man Who Learned Better (1948 – 1988) form a two-volume hagiography of famed science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein (1907 – 1988).

The first of these two volumes was released with what I remember as considerable fanfare on the tor dot com site. The second, so far as I remember, was not1. Why the difference? A cynic would say that by the time The Man Who Learned Better appeared, people had read and commented on Learning Curve.

It is quite clear that Patterson held Heinlein in very high regard.

Heinlein’s third and final wife Virginia appears to have been a determined guardian of Robert A. Heinlein’s reputation and legacy. She selected William H. Patterson for the honour of writing the authorized Heinlein biography. I don’t know that she ever revealed her criteria; I’d be very interested to know what they were.

The problem with the Patterson bio boils down to its uselessness as a source of factual information. Actually, that’s not quite true: I am fairly confident statements and assertions that Patterson attributes to Heinlein were said by Heinlein in more or less the form Heinlein said. When supplying an uncritical transcript of Robert and Virginia Heinlein claims, Patterson likely rarely erred. I mean, I’d still check the end notes2, but I’d expect verification.

Outside of Heinlein’s own papers and those of the Heinleins’ most adoring friends, the two volumes do not appear to have been subject to intensive fact checking. Patterson asserts confidently versions of events that are not only not true, but that can be easily shown not to be true. Take for example, this heartbreaking account on page 342 of my ARC:

Much of the island’s civilian population [the Japanese soldiers] herded onto the heights of Mount Suribachi, where they were encircled. The Japanese forced civilians up — and over — the precipice as they defended the mountain to the last cartridge.

This never happened. Iwo Jima’s civilians were evacuated from Iwo Jima long before Battle of Iwo Jima. There being no civilians present to massacre, the Japanese soldiers refrained from massacring civilians.

The Battle of Iwo Jima is not obscure. What Patterson’s description says is that not only was Patterson unfamiliar with the Battle, but also that at no point was the MS run past anyone with the most rudimentary knowledge of WWII. Which, given how important the war was to Heinlein in particular and the world in general, is simply astonishing.

Similarly, there’s this odd moment in the second volume:

Both of them were apprehensive about going into Argentina, the last fascist state left over from WWII.

A: The Argentine government during WWII evolved from a corrupt democracy to a junta. While some of the government members were fascist, I am not sure if it’s fair to call the junta as a whole fascist. However, even granting for the sake of argument that it was, Argentina was officially neutral until, on 27 March 1945, Argentina declared waron Japan and was therefore on the Allied side. Furthermore, the Heinleins visited Argentina under Peron, who, while he had been part of the junta regime, had been elected afterward. I don’t think the dots between WWII fascist states and Peronist Argentine connect the way Patterson’s line suggests.

B: If junta-era Argentina counts as a WWII fascist state, both Francoist Spain and Estado Novo Portugal do too, in spades, and they lasted well after the period in question.

Maybe the Heinleins were worried that Argentina was a last holdout of WWII fascist states. If so, they were somewhat confused about world history.

On occasion, Patterson’s interpretation of his material appears bold:

Mrs. Heinlein believed the cheers and applause in the studio were for Heinlein’s performance in discomfiting Cronkite3 and that may well have been a factor), but it is just as likely the applause was for Heinlein’s message — and for Heinlein himself.

On what evidence is he basing this?

Patterson once complained his editor, David Hartwell, online [KAREN in a forum that’s since vanished]:

In particular, Hartwell has this bizarre idea that any interiority at all — any statement of an emotion or a thought on Heinlein’s part — must be cited or cut…

Which makes me wonder what the two volumes looked like before Hartwell got to them.

The above is not to say the two volumes lack value. They paint a portrait of Heinlein as Virginia Heinlein wanted him to be painted, based on Heinlein’s own records. The fact that this is what was wanted is itself informative.

I think the two volumes were supposed to provide a positive image. In large part it is not, because Heinlein comes across as bombastic, overconfident, proud, and thin-skinned, not to mention credulous4. That was not what Patterson intended, but there it is.

I hope some day to read a proper, full5 biography of Heinlein by someone who is sincerely interested in the subject matter without being blinded by either hero worship or intense loathing. I have yet to read such a biography6 and welcome suggestions.

Usually, I do a chapter-by-chapter breakdown but I did that with this two-volume set, we’d be here all day.

Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue with His Century, Volume 1: Learning Curve (1907−1948) is available here (Barnes & Noble), here (Bookshop US), here (Chapters-Indigo), and here (Words Worth Books).

I did not find Learning Curve at Bookshop UK, which does not surprise me. I also did not find it at Macmillan, which does surprise me. As well, the price on the Words Worth entry is interesting.

Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue with His Century, Volume 2: The Man Who Learned Better (1948−1988) is available here (Macmillan), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Bookshop US), here (Chapters-Indigo), and here (Words Worth Books).

1: Reactor’s upgraded design does not lend itself to searches.

2: Endnotes often provide context; wordcount limits here prevent my going into details in the body of the review. For example: endnotes reveal that that Heinlein’s uncanny prediction of the Pearl Habor attack is documented in a 1973 Heinlein recollection.

It’s very easy to predict something in 1973 that happened in 1941.

3: USA delenda est.

4: Additionally, the material relating to his second wife provides context for Grace (from Farnham’s Freehold) and the older Belle (from The Door into Summer). This is material I was much happier not knowing.

5: In the sense of being a study of Heinlein in particular, rather than sharing the spotlight with Campbell, Hubbard, and Asimov.

6: This is not a backhanded snipe at Heinlein biographies that I have not yet read.