The Unspeakable Feast

The Citadel of Fear

By Francis Stevens

25 Aug, 2024

Francis Stevens’ 1918 The Citadel of Fear is a stand-alone lost-race dark fantasy.

Determined to find his fortune, American Archer Kennedy recruits a much younger ally, stalwart Irishman Colin O’Hara. Ignoring every warning uttered by Indigenous Mexican locals, the pair march off across an inhospitable desert towards Collados del Demonio — Hills of the Fiend — where Kennedy is certain fortune awaits.

Fortune does await… of a sort.

The pair survive the desert only due to O’Hara’s almost superhuman resolve and stamina. At journey’s end they are astounded to find themselves in a verdant valley. They soon discover they are not the first Europeans to discover the valley. Unlike Kennedy and O’Hara, Norwegian-American Svend Biornson1 appears content to live a quiet life with his family in rustic seclusion.

As the adventurers soon discover, there is more to the valley than Edenic wilderness and lumps of gold the size of oranges. The valley holds the lost Aztec city of Tlapallan. All the wonders of that great civilization that were erased elsewhere after the Spanish conquest thrive in Tlapallan. As do the horrors.

The visitors discover that Tlapallan is divided between two cults. One follows benevolent Quetzalcoatl. The other follows malevolent Nacoc-Yaotl. Between the two there is a careful balance of power. Both O’Hara and Kennedy waste little time finding ways to profoundly offend the pious. Luckily for O’Hara, his virtues mean he is only exiled from the city. A darker fate awaits Kennedy.

Fifteen years later, O’Hara’s beloved sister Cliona marries her doting beau, Anthony Rhodes. Wedded bliss is interrupted by an invasion deterred only by Cliona’s exuberant use of her husband’s pistol. Cliona is traumatized, her husband is upset, and the police are dismissive.

Convinced the claw marks left on the doors and the trail of odd blood left by the wounded invader suggests something other than the hoboes whom the police blame2, O’Hara decides to investigate. The trail leads him to the nearby residence of Chester Reed, Reed’s supposed daughter, and Reed’s eerie albino assistant Marco.

Why does O’Hara sense he somehow knows Reed? Why does Reed populate his home with extraordinary beasts? And finally, having fallen immediately for the supposed Miss Reed, what two-fisted form will O’Hara’s courtship take?

~oOo~

Stevens seems to be doing her best but in general, it’s best not to rely on Wilson-era adventure novels for anthropological education. That said, an aside regarding Nacoc-Yaotl priests. They aren’t the minions of a dark and evil god hoping to spread malevolence across the planet one might expect in the pulp fiction of this era. The priests are the unfortunates whose task it is to keep the bung firmly seated in the bunghole of the barrel of pure evil. Think of them as the guardians of the theological analog of nuclear waste. They’re not pleasant people, but kicking them in the shins as they work is still ill-advised.

The Quetzalcoatl priests are nicer but of course, it’s easy for them to be pleasant, as the god they serve does not crave the horrifying death of all living humans.

Francis Stevens was a pen-name for Gertrude Barrows Bennett (1884 – 1948). Bennet’s writing career was short — 1917 to 1923 — but in that time she wrote a number of influential, well-regarded stories, of which this is one. This is the only Stevens I have ever read3, because it is the only Stevens whose paperback edition made its way in the 1970s to a used bookstore shelf in Kitchener-Waterloo.

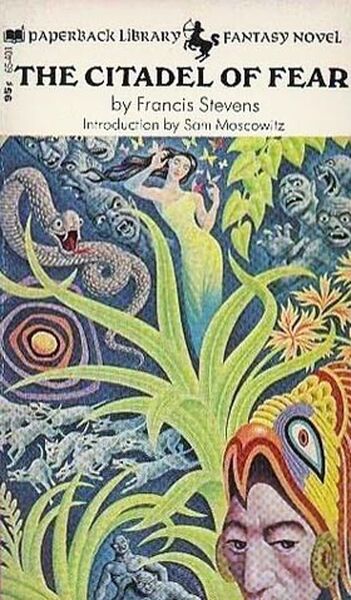

I no longer have that edition, but as you can see below, later editions are abundant. Alas, this means I don’t have the Sam Moskowitz introduction to reread. I do not recall what it said. I do recall, however, that his surname is spelled with a K and not the C the cover claims.

As is so often true, the novel reflects the time of its composition. Both Kennedy and O’Hara are swift to determine the ethnicity of those they encounter, so that the people can be better fitted into the existing pecking order. But the novel is a bit of an outlier in that the protagonist is a noble, heroic, Catholic Irishman4, not the ignorant lower-class type whom Know-Nothings and JD Vance would expect. Also, it turns out that not every native taboo is rank superstition. A lot of it is well-informed, excellent advice5.

Indeed, the plot is driven by Kennedy’s mistaken belief in the ethnic hierarchy of the time. He off-handedly dismisses the warnings of the locals as mere superstition. When he is forced to admit that there is some truth to local beliefs, he reinterprets them as misunderstood science requiring only a mind as brilliant as his to truly master. He is, therefore, the ideal tool for a dark god angered beyond toleration with humanity6.

Stevens’ plotting and pacing are somewhat uneven — there is that fifteen years jump a third of the way through — and her prose features some irritating stylistic quirks. Nevertheless, the story is very energetically told and it does from time-to-time surprise. I am curious about her other works.

The Citadel of Fear is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Apple Books), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Chapters-Indigo), and here (Words Worth Books).

1: This is not a typo for Bjornson. Biornson is an uncommon (one source claimed there had only been seven Biornsons in the US ever, four of them in 1980, which I find difficult to believe) but not entirely unknown spelling, and it is in every edition of the book I could easily check.

2: Critics of copaganda need not fear encountering it in this novel.

3: Conveniently for the James of 2024. not only is Stevens’ work now easily available, the upcoming book by Lisa Yaszek, The Heads of Cerberus and Other Stories, may give us a broader picture of Stevens’ career.

4: A heroic Irishman who is utterly mortified when he accidentally kills a clearly evil minion with a single blow and is only dissuaded with great difficulty from turning himself in to the police.

5: Listen when locals warn “don’t wander into the Desert of Certain Doom and maybe also stay away from the Hills of the Fiends.”

6: The current dark god, Nacoc-Yaotl, has or had more benevolent forms as Tezcatlipoca and Telpuctli. He is kind enough to explain why he no longer manifests in those forms.

“Men made me what I am, and for that I hate them! In all Anahuac there was no mercy among them. In the shrieks of the bloody sacrifice, in the cries of babes murdered upon my altars, in the steam that arose from the unspeakable feast, the mirror of Tezcatlipoca was fouled and dimmed; Telpuctli grew black, old and cruel!”

To paraphrase an old story whose title I forget, having been diminished by men, Nacoc-Yaotl is going to diminish men right back.