Their Wicked Schemes

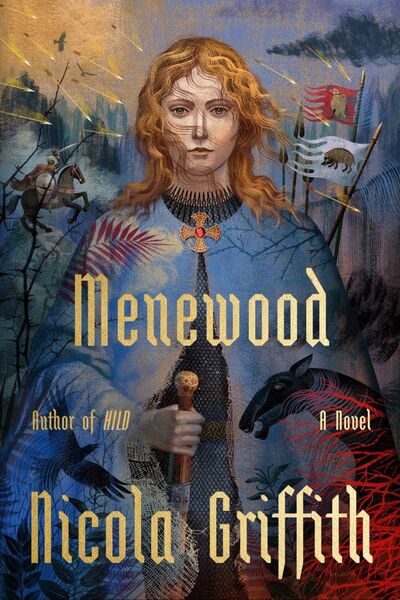

Menewood (The Light of the World, volume 2)

By Nicola Griffith

9 Jul, 2024

0 comments

2023’s Menewood: A Novel is the second volume in Nicola Griffith’s historical sequence, Light of the World1.

Centuries after the Roman exit, Britain is a violent, chaotic land, overrun by waves of continental invaders, beset by ambitious petty kings. Some might dream of a heroic king to unite the land. Certainly some dream of being that king.

Hild on the other hand is a realist who accepts and understands the world around her as it is. War will come. It is Hild’s task to make sure that those about whom she cares will survive it. She cannot expect total success, but she will do her best.

Hild and her husband, Cian Boldcloak, hold Elmet at the behest of her uncle2 Edwin Overking. One might take this as a sign of Edwin’s favor. In fact, Edwin is not at all fond of Hild. The unwary might speculate that it was Edwin himself who had her father Hereric poisoned as a means of furthering his own ambitions. Hild is, however, uncannily wise for an eighteen-year-old, enough to earn Edwin’s grudging toleration.

Edwin’s toleration of Hild is a rare sensible decision from a doomed king whose rule will not otherwise be remembered for its excess of prudence. Despite the cognomen “Overking,” Edwin is only one of many rulers plaguing Britain. Edwin is certain that if he can assemble the right set of alliances, he can prevail. He is almost correct: the right assortment of alliances is the key to a king’s ambition. Just not Edwin’s.

Cadwallon of Gwynedd craves wealth and power. Cadwallon despises Edwin’s people. Cadwallon, despite being as mad as a bag of scorpions, is also more adept politically than overconfident Edwin. Edwin’s trust in his allies is sadly misplaced.

Revelation comes in the form of confrontation, betrayal, bloody massacre, and brutal defeat. Hild is able to flee to safety. Cian dies on the battle field. The child with whom Hild was pregnant dies during the flight. Hild has, it seems, lost everything.

Hild is nothing if not canny. She could not foresee the exact details of the defeat, but understanding Britain as she did, she knew defeat was possible, even likely. Therefore, long before Cadwallon crushed Edwin Overking’s army, Hild prepared a hidden redoubt at Menewood. It is to Menewood that Hild and those few who survive ultimately retreat.

Cadwallon appears unassailable. He has a vast army and he controls strategic locations. Cadwallon appears free to commit genocide in various creatively sadistic ways. As he will discover, Hild is smarter than he is. Is that sufficient or will 634 AD see the future St. Hilda of Whitby (614 – 680) die ignominiously?

~oOo~

It says a lot about the Romans that despite having occupied Britain for almost four centuries, their impact was so evanescent. The Roman exit was followed (or accompanied) by what seems to have been a comprehensive collapse. In this book, parties of armed warriors wander around Britain without encountering each other; the armies are tiny. This suggested that Britain had been depopulated. I did cursory research and found experts claiming that after the Romans left, the British population fell by as much as a million and half — from a pre-exit figure of perhaps two million. No wonder that continental invaders encountered so little resistance.

Not helping matters: Britain’s petty kings’ short-sightedness and dedication to relentless backstabbing. If they are not maneuvering against other kings, the kings amuse themselves by whittling away at their own family trees to clarify dynastic succession.

Seventh century Britain was a stupendously violent, cheerfully cruel place3. Griffith does not sugarcoat this historical reality. Even swift deaths are horrific. Survivors often bear gristly evidence of their injuries. Readers are warned. Not just against this book, but about anything concerning 7th century Britain. Stick to a more peaceful time and place, like 17th century Germany.

Authors of historical novels are hemmed in by recorded facts. For example, it is death to suspense in the novel if we know that Hild died in 680. We cannot be too worried that she will perish in 634. But much else that happens in the book falls within one of history’s blind spots. Griffith has made room for imagination by choosing a protagonist, the future St. Hilda, whose recorded life is sufficiently undocumented as to allow considerable creativity. As the author notes,

Of the rest of the first half of her life — including the years covered in this book, January 632 to March 635 — we know only that she was “living most nobly in the secular habit.” We don’t know where, or doing what, or with whom.

Did St. Hilda’s unrecorded life feature bisexual relationships? Did she fill the undocumented years with spectacular acts of violence with the staff that would later feature in statues of the saint? Good luck showing that she didn’t. That said, Griffith paints within the historical lines. Often with blood4.

As previously mentioned, I currently have a lot of trouble reading long books. Menewood is 720 pages to Hild’s 5465. I deferred reading it in June (also known as Dance Season, when as often as not I am presiding over front of house). I allocated two evenings in July to read it. As it turned out, the book was a surprisingly quick read6, thanks to the author’s deft skill with plot, prose, and characterization.

Menewood is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Apple Books), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Chapters-Indigo), and here (Words Worth Books).

1: I suspect some reviewers might lump Hild and Menewood in with Arthurian stories. In fact, whatever historical figure inspired Arthur (if he were not invented whole cloth like Atlantis) was late 5th to early 6th century, whereas St. Hilda was a 7th century figure. If you want Arthurian fiction from Griffith, seek out Spear.

2: I think Edwin Overking was actually Hilda’s grand-uncle.

3: It can be distressing to look at the relentless stupidity of British rulers, and the long periods of violence and short moments of comparative peace from which British history is woven. To quote from Canticle for Lebowitz’s Dom Zerchi:

Listen, are we helpless? Are we doomed to do it again and again and again? Have we no choice but to play the Phoenix in an unending sequence of rise and fall?

Take hope from geological history. Blessed silence is only a matter of time. Britain is, like other human regions, mainly a stage for appalling acts but unlike many, it is only intermittently habitable. In the last million years, a number of human species have called it home. All but one of them perished. No doubt the latest swarm of chattering hominins will also find themselves ushered offstage, if not by climate change, then by the hydrogen bomb.

4: Reading Menewood back-to-back with Goddess of the River was an interesting experience. 7th century Britain and mythological India have many parallels, not least of which the fact that they featured rulers without whom the common folk would have been far better off. Edwin and Cadwallon would have instantly understood the divisions between the Kauravas and Pandavas.

5: Does this that mean the next book in this sequence will be nearly 1,000 pages?

6: Why can I not finish things if I do not start them?