This week’s discovery

Justice and Her Brothers (Justice Cycle, volume 1)

By Virginia Hamilton

12 Aug, 2015

0 comments

I am continually surprised at the depth and width of my ignorance. Case in point: Virginia Hamilton, an award winning author who was previously unknown to me. I got to be one of yesterday’s lucky ten thousand; now you can be too [1].

Like most adolescents, Justice Douglass — “Tice” to her parents and friends, “Pickle” to her brothers Thomas and Levi — has to deal with change. In particular, Justice finds herself resenting her mother’s late-blooming college career. Each hour her mother invests in schoolwork is an hour less for Justice and her brothers.

It eventually becomes clear that Justice is worrying about the wrong thing. She should be paying more attention to her twin brothers. Thomas and Levi are mirror twins. They may look alike, but one is right handed, one left, one is a leader, one a follower, one is a victim and one … one is a monster.…

The summer rolls by in its dusty way. The brothers busy themselves organizing something they call the Great Snake Race. It gradually dawns on Justice that she doesn’t really understand her brothers or her relationship with them. There is something odd and unpleasant about them, about their interaction with each other, with their family, with their neighbors. Justice slowly begins to grasp just how dysfunctional they are.

For that matter, there’s a lot that Justice doesn’t understand about herself. She is lucky to have a neighbor, Leona Jefferson [2], who realizes that Justice has hidden, unusual abilities and has some idea how to help the young girl access and control them. Leona cannot follow where Justice will eventually go, but she can at least point the way.

The twins also have abilities. Thomas in particular has a gift, a gift as great as Justice’s. As great but far darker…

~oOo~

Like Justice and her initial misunderstanding of the phrase “Great Snake Race.” I too have been in situations where phrases that clearly had one meaning turned out to mean something completely different [3]. It’s like there’s a playbook out there some people don’t get to read.

The author does a nice job of inexorably ratcheting up the tension as Justice begins to notice all the weird crap going on around her — to realize that what she took to be a completely mundane world isn’t. At the beginning of the novel, we might be reading a pleasant coming-of-age story set in a quiet, dusty summer. By the end, we’re biting our nails.

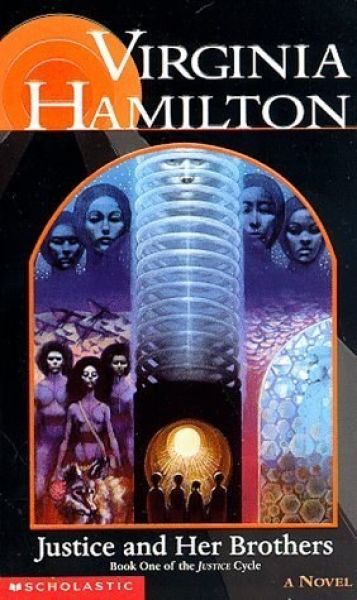

I often research a novel and its author before I read it, but in this case, I didn’t. I didn’t even look at the copyright date. Because I got this through interlibrary loan, an ILL tag covered the characteristic Leo and Diane Dillon cover,

Despite inadvertently denying myself the period clues [4], I still picked up this book’s very 1970s vibe.

Justice read almost as though the author set out to write a juvenile analog [5] of Octavia Butler’s Patternist novels (of which I have only reviewed Wild Seed , although like most people I have read all of the Patternist books). There are definite differences, most striking of which is that the African-American community in this is a rural one, whereas the Patternist books are either urban or post-apocalyptic. While I have no reason to think this and the Patternist novels are set in the same universe, they very easily could be.

Because the cover of my copy was obscured by the ILL tag, I also failed to note that this was Book One of the Justice Cycle. I read this as a standalone. Although it functions well enough as a standalone, the ending is a little abrupt. Now that I know there are sequels, I am very curious to see how the series developed.

Justice and Her Brothers is available from Scholastic.

1: Unless you’ve already heard of Hamilton, obviously.

2: Leona is almost as ominous as Thomas. I found a little Leona went a long way. Actually, I would have preferred less Leona and more Justice. It would have been more satisfying if Justice had been able to work out what was happening and what to do about it, all on her own.

3: And it runs in the family. I once I had a long and very confusing conversation with my grandmother when I told her I came back to the car because I got a little bored and she wanted to know what sort of board it was. This is just one reason why written communication is superior to spoken.

4: Strictly speaking, the cover isn’t a clue. The actual 1970s edition had a Dillon cover but it was a different Dillon cover.

The edition I got, from the 1990s sure looks like it is from the 1970s, though.

5: This isn’t so much because this book is all unicorns and rainbows; there are definitely shadows here. It’s more that Butler’s Patternist books are extremely grim.