Though The Truth May Vary

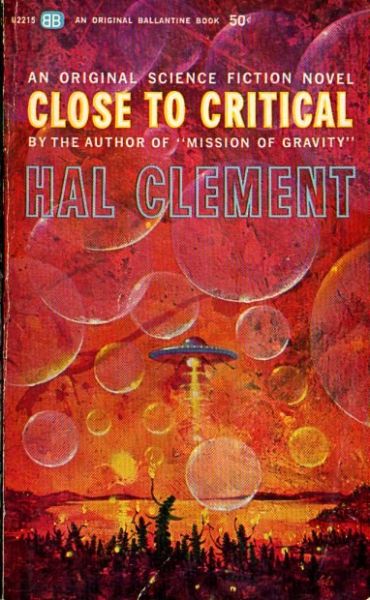

Close to Critical

By Hal Clement

10 Dec, 2017

Hal Clement’s 1958 young-adult adventure novel Close to Critical is apparently set in the same universe as his far more famous Mission of Gravity, but it can be read as a standalone work.

No human could walk unprotected on Tenebra’s surface: if the 8100 kilo-pascal air pressure didn’t crush them, the 374o C mixture of dissolved oxygen and sulphur oxides surely would dissolve them. But as hostile as Tenebra might seem to a terrestrial, it’s a life-bearing planet. Tenebra doesn’t just have life. It has intelligent life and that offers a unique opportunity to researchers up in orbit.

A human-Drommian team has established an orbital observation station circling Tenebra. A telefactored robot serves as their optical receptors and manipulative organs down on the ground.

Sixteen years ago the robot (dubbed Fagin) stole a clutch of native eggs. The entities that hatched from those eggs have now grown into young adults. Having been educated and socialized by their robotic mentor, Nick (so-called by the researchers) and his clutchmates explore Tenebra on behalf of the beings up in orbit. Nick and his chums have an advantage: they are armed with knowledge no other natives have. They have a disadvantage: they lack any real knowledge of their homeworld and their native culture. Nick and company are almost as ignorant of Tenebra as are the orbiting researchers.

When Nick encounters Swift’s tribe, Swift demands that Nick share Fagin’s secrets. When Nick proves uncooperative, Swift threatens violence. Nick flees, only to find himself pursued by Swift’s warriors, all of them experienced hunters. Nick barely has time to warn his companions before the group are attacked. Two of Nick’s clutchmates are killed and Fagin is kidnapped by the Tenebrans.

Nick and his orbital helpers plot to rescue Fagin. The rescue is complicated by an unexpected visit from above. The Drommian Aminadorneldo and twelve-year-old human Easy Rich were allowed to visit a bathysphere prepared for research visits to the surface of the planet. The humans thought that Aminadorneldo was an adult and capable of supervising the young human. But the Drommian is only four years old and rather immature. Childhood curiosity leads to sudden departure. The two children are heading down to the planet’s surface.

Aminadorneldo’s father Aminadabarlee is incensed by human ignorance and failure to supervise. He finds humans cold and unfeelingly logical. He threatens dire economic consequences to the whole human species if his son dies. It is a threat he can deliver on.

Because the bathysphere was launched prematurely, it cannot return to orbit without repairs that can only be carried out by someone outside the vessel. Easy and Aminadorneldo cannot leave the bathysphere without dying. Nick and his clutchmates could make the necessary repairs … if only they could find the bathysphere. Despite being engaged in a deadly game of hide and seek with Swift and his warriors.

If Easy and Aminadorneldo, Fagin and Nick, and Swift and his warriors cannot find some way to work together, the children (and human prosperity) are doomed.

~oOo~

Modern readers may be appalled by the casual way that Fagin steals eggs and raises a clutch of helpless infants to serve as his spies. At the time this novel was written (1958), few readers would have blinked. After all, programs like Canada’s residential school system (First Nations children forced into schools where they were to be turned into culturally white children — if they survived loneliness, despair, and abuse) lasted into the 1990s. I might also mention numerous abuses perpetrated by mid-century scientific and medical researchers.

One might, then, expect that a book of this vintage would cheerfully assume that forcing human culture on aliens is obviously a good idea. Clement, to his credit, shows just what Fagin’s bold gambit has cost Nick and his clutchmates. Such as not knowing what biological sex they might be, or what other Tenebrans might be expect in the way of gender roles.

(It would make an interesting sequel if one were to explore how Nick and chums might have later come to terms with what the humans did to them. Contact the Clement estate? He died in 2003.)

Clement was also somewhat ahead of his time in his treatment of Easy Rich, the human in the bathysphere … who just happens to be a teenaged girl. She is brave and ingenious; she works to save herself and her Drommian companion. She doesn’t wait passively for big brave men1 to save her. The adults on the station may be worried about her ability to deal with her situation but the novel itself isn’t.

Moreover, Clement never subjects the tween to a salacious gaze. Something that male SF authors have been all too prone to do. I’m not saying that SF is wall to wall Republican-style pervos, but I wouldn’t let Heinlein or Garrett or any of a number of classic SF authors anywhere near schoolgirls unless I first equipped those schoolgirls with well-charged tasers. I find it reassuring that Clement, a teacher, was able to focus on the intellectual potential of girls without reference to other budding potentials.

Clement’s treatment of women may be driven in part by a proclivity that informed his world building in many of his novels. He could imagine very alien worlds, but he could never imagine a protagonist who was not reasonably bright and open to logical persuasion. There’s less range between human and Drommian, or Drommian and Tenebran minds than one might find at any two people on Earth. His main characters are usually motivated by curiosity and enlightened self-interest, which means that there’s always the possibility of common ground.

The obverse of this failing was that Clement could extrapolate stories, entire worlds, from phase diagrams. This allowed him to explore settings not all friendly to humans; his worlds were a lot more alien than is common in SF. Other authors pictured worlds that were effectively carbon copies of Earth. Clement went an entirely different direction. If the exoplanets we are now discovering are any guide, we live in a very Clementian universe.

Close to Critical is available here (Amazon) and here (Chapters-Indigo).

1: Well, possibly male. Fagin didn’t do a lot of research on native behavior before kidnapping a bunch of eggs. None of the researchers have any idea how or if Tenebran genders map onto human. They just slapped gendered names onto the natives at random.