Time To Sleep

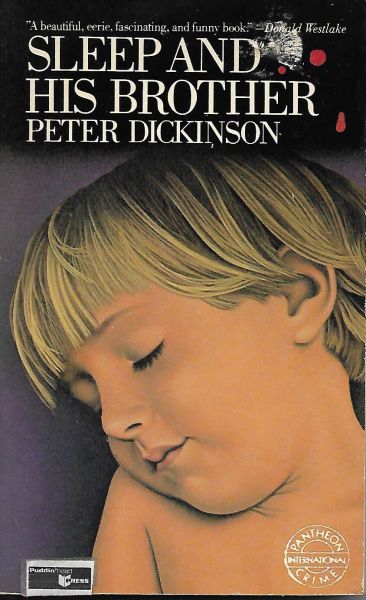

Sleep and His Brother (James Pibble, volume 4)

By Peter Dickinson

17 Jun, 2021

0 comments

1971’s Sleep and His Brother is the fourth volume in Peter Dickinson’s series of James Pibble mysteries.

Sacked from the police for reasons unexplained, James Pibble is spending too much time at home, at least in the view of his wife. She decides to give him a reason to leave the house. Having overheard a conversation that hints of unspecified criminality, she orchestrates a meeting between McNair House’s Mrs. Dixon-Jones and Pibble.

The meeting begins oddly. On arriving at McNair, Pibble is greeted by two enigmatic dumpling-like children.

McNair is a caregiver for cathypnic children, victims of a rare and lethal genetic condition [1]. Cathypnic children are all enormously fat, profoundly cognitively and metabolically impaired, apparently obligately good-natured, and doomed to slip into peaceful but quite terminal comas after short, low energy lives. The one positive of the condition (aside from their general placid cheerfulness) is that adults find them adorable. Cathypnic children do not live long but at least they are lovingly tended.

Mrs. Dixon-Jones explains that Pibbles’ wife has grabbed the wrong end of the stick. Dixon-Jones was complaining to McNair’s patron, Lady Sospice, about interfering busybodies. References to criminality were but hyperbole. Both Mary and Lady Sospice took Dixon-Jones at her word, thus the pointless meeting with Pibble.

Pibble is not so sure Dixon-Jones is being entirely truthful. Perhaps there is some untoward development which she doesn’t want to share with a total stranger. What could it be?

Pibble discovers two items of interest:

- Marylin, one of the cathypnic children, has a personal connection to Samuel Gorton, the notorious Paperham murderer;

- A researcher at McNair House, a certain Ramses Silver, is a conman (which Pibble knows thanks to his previous career).

The first item becomes even more interesting when Samuel Gorton stages a well-timed escape.

The second item becomes personal when Pibble is drawn into Silver’s psychic research project. The enigmatic comments made to Pibble by the two children who greeted him may have been prophetic (at least, they could be interpreted as referring to events about which neither child could have known). This may be the very proof Silver needs for his studies! It’s an odd development; if Silver is planning on defrauding McNair somehow, he is prefacing his crime with what appears to be genuine research.

In fact, there is something up at McNair. It does not involve Gorton or Silver. It does, however, involve potential scientific breakthroughs, egregious ethics violations, and (of course!) impending murder.

~oOo~

This is my first Pibble.

One might expect a book written half a century ago to be somewhat dated in its social views [2]. Sleep and His Brother more than delivers on that. Not only social views in general … very much of the not-yet-having-quite-realized-the-Empire-is-as-dead-as-George VI-era; the attitude towards the afflicted children is best described as grotesquely condescending. Why, it’s impressive that someone on staff manages to find a way to violate the period’s extremely rudimentary research ethics guidelines.

Silver is a bit of an odd duck for a fictional conman. He has in his career posed as professional men across a wide range of occupations. Generally speaking, your Frank Abagnales are in it for the money. Silver, in contrast, seems to genuinely desire to be accepted as that which he pretends to be and is rather bitter that the state has punished his sincere efforts simply because he lacks genuine credentials and actual training.

This is a strange little country estate murder mystery, starting with its central figure. Pibble is observant. He does not seem to be highly motivated to do much with the odd details he notices. Of course, no longer being a policeman, it is no longer his job to tackle crimes. Nevertheless, readers should not expect guns hung on the mantlepiece to be taken down and fired, at least not in a conventional manner. Gorton’s escape in particular is a total red herring, although no doubt very bad news for one or more women elsewhere in Britain. The possibility of Genuine! Psychic! Powers! Is raised but left ambiguous. Pibble is for the most part content to bob around the periphery of the plot as a nearly passive observer.

What the novel appears to be is a study of clashing obsessions. Most of the characters have something on which they are focused to the exclusion of all other matters. Inevitably, these obsessions conflict, in this case with spectacular (if somewhat unresolved) results.

Sleep and His Brother is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Book Depository), and here (Chapters-Indigo).

1: A Google trawl turns up no hits for cathypnic save in reviews of this book. It appears to be a made-up disorder.

2: Although researching the condition may well produce valuable results and the betterment of humanity in general, a supporting character in the book cautions against expecting the children to benefit in any way. The condition, this character assures Pibble, is far too rare to be worth the investment needed to find a cure.