Tomorrow is Now

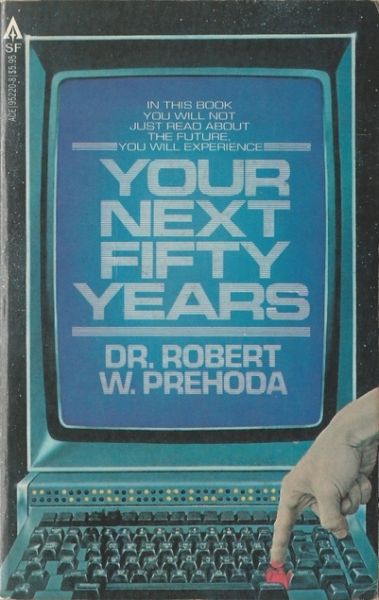

Your Next Fifty Years

By Robert W. Prehoda

12 Jan, 2020

Robert W. Prehoda’s 1980 Your Next Fifty Years sketches out a possible future for 1979 – 2029. While 2029 is still some time off, we’re far enough into this period that we can judge if he got it right.

Spoiler: no.

Foreword by Jerry Pournelle

A glowing foreword, slightly marred by the fact Pournelle thinks humans suck too much to take advantage of the technological paradise science offers.

In truth, I doubt we will reach Prehoda’s world no matter what we do; his vision is too bright for that. I cannot believe that wealth for all will melt away every human conflict; there will remain, in my judgment, a number of unsatisfactory people: paranoids, the greedy, the slothful, the stupid, and they will create problems enough.

Acknowledgments

Self-explanatory. Impressively long.

Preface

Your Next Fifty Years is a projected history. It is not science fiction, but extrapolated science describing the practical developments that will grow out of research in the physical and biological sciences. This data, when integrated with social and political trends, permits a realistic projection of what we can expect during the next half century.

2029: A Transformed World

Prehoda takes the reader on a tour of the 2029 they might live to see, from electric cars to ubiquitous robots. IAN, a centralized super-computer, runs this perfect world. We can expect space industrialization. video-phone conferences, fusion power, and firm but fair population control laws. We’ll have advanced medicine that will include

super-cosmetic surgery that allow even radical alterations in racial characteristics.

On Forecasting the Future

A brief overview of the tools that can be used to predict the future.

Comments

I think at least one of the charts in this section is lifted from Herman Kahn, whom Prehoda acknowledges later as a significant futurist. Mind you, he also thinks Heinlein was the bees knees when it came to predicting the future, which only makes sense when you consider all the cities on rails we have today.

An interesting difference between Prehoda and Vinge is that Prehoda is aware of S curves: a field can advance rapidly as the easy gains are made and then stagnate once further advances fail to materialize.

1989: The Post-Orwellian Future

While certain Eastern nations languish under totalitarian rule (in particular China, now ruled by New Leader because apparently with communism comes a lack of names), propaganda reels assure the reader that the West has escaped this terrible fate. The means by which this has been achieved are all-round common sense and a rejection of silly ideas.

The crime waves of the past have been solved with draconian prison terms and Doc-Savage-style brain surgery that fixes addicts’ brains. Large cities have declined; thanks to videophones, people can work from home. Why, even housewives can be productive members of society, thanks to sensible tax laws that encourage:

many of these “video-secretaries,” sited in small towns or rural farms, to hire former welfare mothers to perform domestic tasks and certain aspects of child care, while they are busy working at a desk.

Not only does this optimize using each person’s potential, it removes the welfare mother’s children from the vicious urban environment which could only lead to rampant criminality.

1994: The Year of the Malthusian Crisis

Exploding population, pollution, and the never-ending threat of global cooling leads to a series of subpar crops, which in turn leads to widespread famine, which in turn leads to the deaths of a billion people in foreign nations (not the reader’s country, no way). Poor New Leader dies without ever getting his own name.

In the wake of the Malthusian Crisis and the Indo-Pakistan Nuclear War, everyone who matters agrees to disarm and to regulate population.

Comments

Prehoda underestimates the world population of 1994, which turned out not to be massive enough to cause mass starvation.

1999: Visit to Micropolis

A tour of the wonderful cities of tomorrow, which are capped at 200,000 people; large enough for essential services, small enough to avoid creeping cosmopolitanism.

Comments

A litre is a litre no matter the shape of the vessel; a million people are still a million people, whether they are in one city or five. If you divvy them up, that means duplicating various services. But hey, at least everyone gets to live in their own version of Brantford.

2004: Robots and the Intelligence-Amplifier

Moore’s Law (not by that name) facilitates both powerful central computers and autonomous robots, both of which greatly amplify human productivity.

Comments

I don’t know why futurists had such a blind spot where personal computers were concerned but it was pretty ubiquitous. At least Prehoda acknowledges the potential of computers, whereas around this time his hero Heinlein was saying

There is some new gadget in existence today which will prove to be equally revolutionary in some other way equally unexpected. You and I both know of this gadget, by name and by function — but we don’t know which one it is nor what its unexpected effect will be. This is why science fiction is not prophecy — and why fictional speculation can be so much fun both to read and to write.

(No, I still don’t know what that revolutionary gadget is — unless it is the computer chip.)

2009: The World Set Free

Clean, efficient, and reasonably sized fusion reactors coupled with a hydrogen economy solve the energy problem once and for all.

Comments

Have I mentioned I hate liquid hydrogen? Low density and hard to work with. Prehoda acknowledges that one can circumvent most of the issues with hydrogen by adding carbon atoms to produce high energy density fuels that are conveniently liquid at room temperature.

Interestingly, Prehoda knows that the p+Boron11 fusion is not entirely aneutronic. He is writing well before Lunar He3 became a thing and hasn’t contracted the He3 fusion bug. Importing helium from space (by harvesting it from Earth’s exosphere) is a thing, but Prehoda means He4, which is as we all know a commercially valuable, non-renewable resource we’re quickly squandering.

2014: Methuselah’s Children

Science punches aging in the nards, creating a paradise of youthful baby-boomers.

2019: Project Cyclops

We are not unique and the nearest world of aliens willing to talk to us is not so far from us in cosmic terms. This is still far enough that communication will take centuries.

Comments

The aliens don’t seem to go in for interstellar travel. They’re also far more advanced than humans. These two facts might militate against plans for crewed interstellar ships.

2024: The Third Industrial Revolution

Thanks to the space shuttle and the era of cheap space flight it ushered in, the Solar System’s endless bounty is ours for taking!

Comments

This is basically Harry Stine’s The Third Industrial Revolution, précis version. One very interesting detail: humans being delicate meat sacks are not the core around which the 3IR is built. Cheap, expendable robots are.

2029: Technological Shangri-La

Everything is awesome! Also, and isn’t it fun that this is notable enough for me to point out, Muslims exist in this shiny universe as something other than something with which to scare Fox viewers.

Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow

A discussion of the potential of the future, futurism, and why Prehoda’s vision of the future differs from that of other famous futurists. Unsurprisingly, Garrett Hardin gets a big shout-out; although Prehoda doesn’t seem to be quite the virulent bigot Hardin was, he is in his own worlds a “technophilic-Malthusian.”

Appendix A: The Principle of Optimization

There is one vital factor that makes the technophilic-Malthusian perspective unique among alternate approaches to long-term forecasting. It is based on the Principle of Optimization which can be viewed as a fundamental law of nature. (…)

The Principle of Optimization can be defined in 117 words:

There is an optimum size or quantity for anything when it is subject to certain environmental influences and must continue to function within the constraints imposed by this same set of environmental influences. The “optimum size or quantity” is subject to change if one or more of the environmental parameters is altered. “Anything” can be a living or nonliving entity. “Anything” can also be the size of a population of living or nonliving entities. “Anything” can even be a way of life — a “life style” or pattern of living. For some functions the principle applies to the shape or configuration of an entity. It can also apply to the internal organization of component or subsystems within an entity.

That sounds like common sense. To quote a well-known pundit “you would make that conclusion walking down the street or going to the store.”

Footnotes

Self-explanatory.

Index

Also self-explanatory but kudos for having an index.

General comments

Prehoda got one thing right… well, two, but both with asterisks. He foresaw that Moore’s Law meant computers would become more powerful, but not that they would become ubiquitous in the manner that they did. This was a very common failing in olden times (lots of Hals and Colossuses and Multivacs, not many predictions that one day humans would be able to email their toasters).

He was also right about crime rates dropping (which much have made him unique in his social circles) but not why. For some reason mandatory brain surgery on drug addicts failed to materialize. Probably it would be unkind to wonder if being a Hardinist1 made him more inclined to expect heavy-handed authoritarian solutions to prevail; after all, he might have acquired that tendency merely by standing too close to Jerry Pournelle.

Otherwise… oh, well. It’s not like books like this were intended to be read forty years down the road. The Inevitable Malthusian DOOOOOOOOOOOM stuff played well in the 1960s and 1970s,

I have no idea what became of Prehoda. I did find one rather hostile obit but the writer seems to have an axe to grind.

While this book is useless as far as prediction goes, there are some interesting aspects. The book is written in a breathless manner with the reader themselves as the viewpoint character. I regret to inform you that you will spend half a century asking leading questions so that other people can lecture you interminably.

As well, even by the standards of science fiction and its ancillary fields, this has some of the most shameless name-dropping and sucking up to the author’s SF buddies that I’ve ever seen. Prehoda really broke out the knee-pads for this book. If you’re not sure how flamboyant obsequiousness works, I recommend this work.

Your Next Fifty Years is out of print. If, after this review, you still want to read it, it’s available at several online used bookstores. If you want a new copy, Bennett Books will sell you one, for prices ranging from $98 to $128. Deal!

1: I do see parallels with Stableford’s The Third Millennium and his Emortality series. I am sure Stableford has Hardinist tendencies. QED.